Tommy James had an incredible run in the 1960’s and early 1970’s, with hit songs including “Hanky Panky”, “Crimson and Clover”, “I Think We’re Alone Now”, “Mony Mony”, “Sweet Cherry Wine”, “Crystal Blue Persuasion”, and “Draggin’ the Line”. Several of these songs became hits again in the 1980’s when they were re-recorded by Joan Jett (“Crimson and Clover”), Billy Idol (“Mony Mony”), and Tiffany (“I Think We’re Alone Now”).

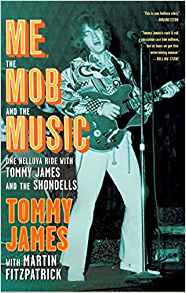

Amazingly, James did his recordings for a record label which was a front for a Mob family, a story detailed in his book “Me, the Mob, and the Music”, and which will be turned into a movie biopic in the next few years.

This interview was done for a preview article for noozhawk.com for James’ concert at the Ventura County Fair on 8/6/19. It was done by phone on 7/30/19. (Publicity photo)

Jeff Moehlis: It turns out that the very first interview that I did was with Jeff Barry.

Tommy James: Is that right? Jeff’s a friend of mine. He produced one of my albums.

JM: And you probably know that he lives out here. He’s a super nice guy.

TJ: He’s a very nice guy, and very talented. I mean, the guy really made a lot of hits.

JM: What inspired you to record “Hanky Panky”, one of Jeff’s songs?

TJ: I heard another group play “Hanky Panky”. Now, we had just signed a little label deal back in my hometown of Niles, Michigan. This was back in ’63. I was in high school, and I had my band The Shondells. And I worked in a record shop after school, and the fella who was a local DJ started a label and asked us to be on it. So we released one record, and it was OK. You know, it didn’t do much.

So we were really looking for another song to record, and I happened to go out a lot on Sundays to a club and would see the bands play, and this one group called The Spinners – it wasn’t the R&B group [laughs] – a local group called The Spinners played this song called “Hanky Panky”. And I saw what it did to the audience. I had never heard the song before, and the audience asked for it a half dozen times over the next couple hours, and the band kept playing it. And I said, “We’ve got to do that.”

I couldn’t remember all of the words to the song. All I could remember is “My baby does the hanky panky” [laughs], so we went into the studio. We recorded it in a little radio studio in Niles, and made up a bunch of lyrics and did the one line I could remember a hundred times, and put it out. It was a big local smash, and we started playing it at all the dances. But we had no distribution to speak of, so the record kind of died. It was big in about six counties, and then stopped. This is all in 1963 and 1964.

We kind of forgot about the record, and I graduated from high school in ’65, and I took my band on the road. We’re playing this dumpy little club in Wisconsin, and the guy goes out of business right in the middle of my two weeks. So we went back home feeling like real losers, and the minute I got home I got a call from Pittsburgh that “Hanky Panky”, this record that I had recorded two years before, is suddenly sitting at Number One in the city of Pittsburgh. What had happened was that one copy of the record ended up… this is just the Good Lord working, pure and simple. One copy of the record ended up in the hands of a local disc jockey, who was on the radio and playing dances on the weekends with his records, and he’s playing it for the kids and they’re all going crazy. And they bootlegged the record and put it out in Pittsburgh. They sold 80,000 of them in ten days. It was the biggest record Pittsburgh had ever had, and we’re sitting at Number One.

Well, on the record it says Snap Records / Niles, Michigan, and they track me down. If I hadn’t been home at that exact moment, I would’ve never gotten that call. You and I wouldn’t be talking [laughs]. They told me, and I couldn’t believe it. I went to Pittsburgh. I couldn’t put the original Shondells back together, so I picked up the first rock band I could find in Pittsburgh and brought them with me to New York, and we ended up selling the master to Roulette – that was a whole story in and of itself – and Roulette Records then took it Number One all over the world. It ended up being the biggest record of the summer of ’66, and of course went Number One in the nation then. Like I say, that’s just the Good Lord working, because there’s just so many coincidences and so many things that could’ve stopped it dead in its tracks. I’m just amazed it ever happened. The longer I’m in this business, the more I realize what an amazing fluke that was.

JM: When you were recorded “I Think We’re Alone Now”, did you think you had another big hit on your hands?

TJ: I really did. I believed in that record. They brought it to me as a ballad, believe it or not. We went in the studio and put the eighth notes in – you know the “doom-doom-doom-Doom” – and we did a demo and took it back to the record company. Morris Levy, who was the head of the label, loved it. I actually recorded the vocal on Christmas Eve of 1966, and what a Christmas present that was. That was one of those records. Bo Gentry and Ritchie Cordell, who wrote the song, then became my producers. We had a nice string of hits with Bo and Ritchie.

JM: Your second Number One song was “Crimson and Clover”. How did that song come together?

TJ: Well, basically it was just two of my favorite words that I glued together, and it sounded profound [laughs]. “Crimson and Clover” was a a title that I sort of dreamed up as I was getting up one day. I had dreamed it, kind of.

We wrote three different songs called “Crimson and Clover” until we found the one we really liked. I wrote it with my drummer Pete Lucia, and we went into the studio and it ultimately became the biggest single saleswise that we ever had. Five and a half million right there in February and March of 1969, and then went on to do probably about ten million singles when you add it all up on all the packages. It was a platinum album, and then it was out on various packages all over the world.

It was such an important record for us because “Crimson and Clover” allowed us to make the jump from Top 40 AM singles to FM album rock. You know, it allowed us to make the jump from singles to really selling albums after that. And I don’t think there’s any other single record that we ever put out that would’ve done that in one shot like that. It was amazing, because we were out on the road with Hubert Humphrey, the Vice President when he was running for President, and he ended up doing the liner notes to the Crimson and Clover album. So it was a real turning point for the group.

JM: I grew up in the ’80’s, so I remember hearing “Crimson and Clover” by Joan Jett.

TJ: That’s the way we would’ve done if we had done it 20 years later. She left the hard edges on it, and really turned it into a different kind of a record. She did a great job. You know, a couple of years ago I did it with Dolly Parton. Dolly put it on her album. We did a duet of “Crimson and Clover” – she did her half in Nashville, and I did my half in New York – and we got together at Radio City where she did a concert. And I did it a couple years ago with Joan Jett on the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Show – it’s on YouTube. It was me and Joan and Miley Cyrus and Dave Grohl all onstage at the same time doing “Crimson and Clover” – you know, four generations of rockers, so it was really quite an event.

JM: Joan Jett did that, Billy Idol did “Mony Mony”, Tiffany did “I Think We’re Alone Now”. Those were all hits in the ’80’s. Why do you think those songs translated so well across generations like that?

TJ: I just think there’s just great energy in the music. There’s other groups I feel that way about like The Beatles and The Beach Boys. There’s just good energy in the music, and they work with so many different kinds of arrangements. You know, we just did “I Think We’re Alone Now” as a ballad for the [upcoming biopic] movie, and it’s out as a single. We’re Number 29 this week in Billboard on the AC charts with “I Think We’re Alone Now”, the acoustic version. We did it acoustic and slow, completely unlike the original record. So I guess it’s just that the songs work so well with different kinds of arrangements. You can do them as a dance record, you can do them as a ballad. I’m waiting for the jazz version [laughs].

JM: I want to ask you about one of your songs that wasn’t a single or a hit, definitely an album track – “Cellophane Symphony”. What’s the story behind that song?

TJ: This is a true story. My usual studio Allegro [Sound Studios] was being shut down for a few weeks for updating. I think they were going to 24-track at that moment from 16-track. So I had to book another studio, and I booked a little studio called Broadway Sound up on 54th and Broadway. I walk into the studio, and the first thing I see is this gigantic machine that looks like an old switchboard from the 1920’s. “Number please?”, you know, with the jack plugs and everything, and a keyboard on it. And I said, “What the hell is that?” And he said, “That’s a Moog Synthesizer.” That was the very first analog synthesizer in New York.

The studio and the synthesizer was owned, believe it or not, by Whitey Ford from the New York Yankees. Whitey Ford! He takes me out to lunch, and if you wanted to hear a funny conversation you should’ve heard me talking baseball and him talking rock ‘n’ roll. It was hysterical. But anyway, we get back and I start fooling around with the synthesizer, and it can be a drum, it can be a trumpet. It was all monophonic – you couldn’t make a chord with it – but it could be any instrument. I just knew that that was future, that that was going to be a big part in electronics and in music in the future.

So we started playing with it, and the first song we came up with was “Cellophane Symphony”, which meant “plastic music” to us. We did the album, and for a bunch of the songs on it we used the synthesizer. All I can say is that they weren’t really ready for it at the time. But several years later, in 1975 and 1976, all of a sudden the album exploded again out in the Midwest, and started selling. That’s where most of the sales actually came from for the album. So, anyway, Cellophane Symphony has turned out to be one of the hallmarks of our recording career. It was not the biggest album at the time, but it ended up being the one we’re probably the most proud of.

JM: I know you wrote a whole book about this, and there’s a movie in the works. In a nutshell, what was the good, the bad, and the ugly about your record deal with Roulette Records and Morris Levy?

TJ: The good part was that we had very little competition on the label. Let me tell you, when we took “Hanky Panky” around originally, we got a “yes” from everybody, all the major labels. So I went to bed that night feeling real good. We were going to be with Atlantic or CBS or one of the corporate labels. And the next morning, about 9:30 or 10:00, we started getting calls in our hotel room in New York. All of the record companies that had said “yes” the day before were suddenly calling up and saying, “We’ve got to pass.” I said, “What do you mean?” Finally, Jerry Wexler at Atlantic told me the truth, that Morris Levy, the head of Roulette Records, called up all the other labels and scared them to death, and said [in a deep, gruff voice], “This is my fucking record.” [laughs] That’s just how he talked.

And then we find out what Morris Levy was. Morris Levy, who was the head of the label, was involved deeply… Roulette Records, plain and simple, was a front for the Genovese crime family in New York, and we didn’t know that. We were apparently going to be on Roulette because when Morris got through, that was the only label that we could go on. It was the first offer I couldn’t refuse. So we signed with Roulette Records and gradually learned who exactly we were involved with, because these mob guys who we would see on TV were all hanging out up at Roulette. They used it like a social club. So, as you know, we had to be very careful because we couldn’t talk about any of this, and we couldn’t tell anybody. A lot of people knew inside the business, but all I knew was we were having one hit after the other.

You know, the bottom line is that, strangely enough, we had tremendous success on Roulette that I don’t think we would’ve had anywhere else, because anywhere else we would’ve had a lot of competition on the label itself. There would’ve been a lot of other acts, and if we’d have gone, for example, to CBS or somebody, especially with a record like “Hanky Panky”, we would’ve been turned over to the in-house A&R guy, and that’s probably the last time anybody would’ve heard from us. At Roulette, they actually needed us. They hadn’t had a hit in a couple of years. So we got the red carpet treatment at Roulette. Of course, getting paid was another story [laughs]. Crime doesn’t pay, you know? So anyway, that’s the long and short of it at Roulette. We were lucky to make it out of there in one piece, because we had some very scary moments up at Roulette. So the bottom line is God bless the crooks [both laugh], you know what I mean?

JM: What is the status of the movie right now?

TJ: They just made the announcement in Variety last week. Our director is Kathleen Marshall and our is producer Barbara De Fina, and the screenplay has just been written by Matthew Stone. The next thing they’re going to do is casting. Now that the director has been chosen, things are going to move much faster.

You know, development goes on and goes on, and every person that comes on the team is a separate negotiation. I’m getting a hell of an education putting this all together [laughs]. You know, everybody that comes on is not only a separate negotiation, but you have to work out time schedules and everything, so that everybody can be available at exactly the same time. So it really is an amazing feat putting a movie together.

By the way, Barbara De Fina produced “Goodfellas”, “Casino”, “Hugo” a couple years ago with Martin Scorsese. She’s an amazing producer. Kathleen Marshall came from Broadway, so they want to do a Broadway musical after the movie. So the next couple of years are going to be interesting. We’re probably looking at another 18 months to 2 years.

JM: Do you have any thoughts on who you want to play Tommy James in the movie?

TJ: Well, I have a lot of thoughts, but the point is there’s so many young, hip actors out there who are also musicians. I think Jamie Foxx really raised the bar when he did the movie Ray, because he not only sang like Ray Charles, he looked like him. It’s incredible. So we’re going to have to find somebody who fulfills all that. Morris Levy is going to be another one of the characters who really has to be the right person. You know, they have to be both perfect for the part, and good box office at the same time. That’s the tricky part, and I’m leaving that to Barbara De Fina and the grownups [laughs], because I’m the worst at it. You know, these young casting directors are very hip. They know everybody who’s new and available, and who would be great.

People ask me if I’m going to do a cameo in the movie, you know a bartender or something. I think what I want to do is become a corpse [both laugh]. I want to play a corpse. The lines are really easy, and you don’t have to worry about missing your mark. So anyway, that’s the story with the movie.

JM: You really covered a lot of musical territory back in the ’60’s and early ’70’s. What inspired you to take such an eclectic path, rather than just doing “Hanky Panky” over and over again?

TJ: Well, look, if you’re an artist, I think your job as an artist is to keep pushing people [laughs]. To not only keep the music coming, but to take chances, and to put yourself in different situation so that you make different kinds of music. Stretch – I guess, is what I’m saying – as far as you go. And take chances.

We have a brand new album out right now called Alive. It’s our first studio album in ten years. I’m just really very proud of this album. It’s all over the place musically. You can’t say it’s got a theme to it, it’s just all over the place musically. It’s doing real well for us. I told you, “I Think We’re Alone Now”, which we released from the album and which is going to be in the movie, it jumped on Billboard in the 30’s and it’s [Number] 29 this week on the AC charts. So we’re just going to continue releasing singles.

I have a show on Sirius XM every week. It’s called “Getting Together’, and it’s on every Sunday on 60’s on 6 from 5:00-8:00PM Eastern time. There’s so much going on right now between the movie and the radio show, and we’re on tour. When I say we’re on tour, we’re basically doing the weekends – that’s all we have time to do because I’m in the studio during the week. I never thought in a million years we’d be doing this 50 years later. I really do thank the Good Lord and the fans for the kind of longevity we’ve had.

JM: Another thing that strikes me is that you were really young when you had all those hits in the ’60’ and ’70’s. How did you keep your head on straight when you were having having so much success as a teenager and in your early 20’s?

TJ: It’s like being in the eye of a hurricane. That’s the only way I can describe it. You know, I went from a little town in Michigan to New York City overnight, and I just had to be ready. I was very lucky to have terrific people in my life. Strangely enough, the record company was really run by the mob, but there were many good people in it. They had a promotion guy Red Schwartz who taught me the radio business. Because I was at Roulette rather than CBS or somewhere, I got a real street-level look at the business, the business of the music business. That is, I got to know who the distributors were, I got to know all the promotion guys, I got, eventually after Bo and Ritchie, to produce myself. So we did the songwriting, we did the production, I even got involved in the album covers. So I got to learn my craft. I got to learn every bit of the music business at a real street-level. So I got a great education.

I didn’t always live like it. I mean, we were doing drugs in the ’60’s like everyone else was doing, and I’m not real proud of that. But we did the ’60’s. I became a Christian later on. Really starting in 1967. I didn’t live like it very much, but God was always looking out for me, and thank God when I finally did come to my senses and quit all that stuff, He was right there with me. I have a wonderful wife Lynda, and a terrific son Brian. So I sort of feel like I have the best of all the worlds. I’m very fortunate, very blessed, and the fans have stuck with us all these years, and we have new fans all the time. I look out at our concert crowd now, and I see literally three generations of people. It’s quite amazing.

JM: What advice would you give to an aspiring musician?

TJ: I get asked that a lot. I think to any young artist who wants to get into the music business, now is the toughest time I’ve ever seen for new acts to get exposed. Strangely enough, even with all of the new digital devices and with all of the ways you can get onto iTunes and YouTube and everything, because there’s so much of it, it’s very hard for an act to get singled out and noticed.

I think the best thing a young singer-songwriter could do is instead of going to a record company, go to a publishing company, because that’s where the action is. If you could put a dozen of your songs together, and put them on a demo – get a tape or a disc of your music, get them recorded even if they’re real half-assed, just get them recorded – and take them to a publisher. Go to one of the majors. Go to EMI or Sony, or to one of the major publishing companies. Go in business with them.

The first thing a publisher will do if they like the songs is they’ll want a piece of it. Get it to them. Go in business with them. It’s great having a partner with clout. You could split your publishing with one of the major publishers, and then the publisher will take you to a label, or the publisher will get your songs in movies or in commercials. Go at it that way, at least right now.

Record companies are not signing people. They’re not much interested. They want you to do the work. They want you to have the following, they want you to have all the fans on Facebook and everything. So I would invest in yourself, get your songs demo’d, then go to a publisher and go in business with them, and take it from there. That’s what I would do right now if I was starting out. That’s also where the money is.

It was much easier in many ways when I started out, because everybody was looking for the next big act. Radio and TV and all the record companies were all on the same page. That’s not true anymore – they’re all going in different directions.

Discussion

No comments for “Interview: Tommy James”