Jeff Barry is one of rock and roll’s most accomplished songwriters. He was recently selected for a 2010 Ahmet Ertegun Award by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Barry and his songwriting partner Ellie Greenwich co-wrote such early rock and roll classics as “Be My Baby”, “Da Doo Ron Ron”, “Chapel of Love”, “River Deep, Mountain High” (all co-written with Phil Spector), “Leader of the Pack” (co-written with George “Shadow” Morton), “Hanky Panky,” and “Do Wah Diddy Diddy.” Later, Barry co-wrote the bubblegum smash “Sugar, Sugar” with Andy Kim, and theme songs for the television shows “The Jeffersons,” “One Day at a Time,” and “Family Ties.” Barry also was the producer for many well-known songs, including “I’m A Believer” by The Monkees, and early Neil Diamond songs such as “Girl, You’ll Be A Woman Soon” and “Kentucky Woman.”

This interview was conducted in person on May 6, 2008 in Santa Barbara, California.

Jeff Moehlis: When did you first start writing songs?

Jeff Barry: Well, that I know of, when I was seven. My Mom wrote a song down that I wrote when I was seven. So that’s the earliest I know of doing.

JM: Do you remember the song?

JB: Yeah, actually I do. It didn’t have a title, really. But it was:

I got a gun, and I got a saddle, and I got a pony, too

I wish I had a sweetheart, a sweetheart like you

I got a gun, and I got a saddle, and I got a pony, too

I even have a sweetheart, and that sweetheart’s you

If you got a gun, and you got a saddle, and you got a pony, too

You oughtta get a sweetheart, I’m tellin’ you.

That was it.

JM: That’s pretty good for a seven year old!

JB: I stayed interested in things cowboy and ladies. Or, love, I should say. Trying to figure it out.

JM: Did you ever have any formal musical training?

JB: No, not really. I took one piano lesson. I was a terrible student. And I took a couple of upright bass lessons so that I that could fake it and perform with a quartet in the Catskill Mountains of New York. Because I wanted to sing with the quartet, and the budget didn’t [allow] for a fifth person. They said, but if you can fake the bass you can sing as well. And I took a couple of drum lessons. That’s it. So nothing formal, really.

JM: How did you end up getting a job working at the Brill Building [the legendary building at 1619 Broadway in New York City where literally hundreds of early rock and roll hits were composed]?

JB: Well, it was a move, really that’s all it was. I was signed to a music publisher who was in the Brill Building. That was “TM Music”. They sold their company to Bobby Darin, at the time, and I was a staff writer. They said, we don’t really feel right about just selling your contract if you don’t want to be, you know, under the new organization. So Darin flew me out to California, and I spent a week out here, getting to know him and hanging out. It was very interesting, a lot of fun. And I did opt to not sign up. Because after the sale I would have been the “big cheese” there. I remember somebody once said, “always try to be around someone who knows more than you do.” And there wouldn’t have been anybody.

A couple of doors down the hall in the Brill Building was the Leiber and Stoller organization/publishing company. They offered to sign me, and bring me over there, and so I did that.

JM: In the early 1960’s at the Brill Building, you worked with your then-wife Ellie Greenwich. What did each of you bring to the songwriting partnership?

JB: Well, when I come to the songwriting table, my first responsibility is lyrics, ideas, titles. Secondly, melody, and lastly, chords. When I write myself, they’re usually four, five chord songs, tops. But Ellie was a music major, so the answer, I guess, is more sophisticated chord progressions and options, harmonic options and so on. Which is what I seek out in anybody I write with. I really like to write the part the singer sings: words and melodies.

JM: In the 1960’s, you also co-wrote with Phil Spector. What did he bring to the songs?

JB: He would invariably be at the piano, so once again it would be the chords. When writing with Phil, it was more writing for him, for his acts. By the time I was writing with Phil, I never wrote songs anymore to make a demo to try to get records. Either I was going to produce it or the person I was writing with [would produce it]. Obviously it doesn’t 100% work out that way, sometimes artists come to you for songs, and sometimes they hear them. But basically that was it. So when writing with Phil it wasn’t to just write a song, it was for him to record.

JM: So he typically had a specific artist in mind?

JB: Yeah, it would be an artist on his label. So what he brought to it was him, you know, writing what he wanted to record. I’ve always said, if someone said to you, “you have three hours to write a hit, and you can choose one person to write it with”, it would probably be Phil. Within the first hour we would have something that sounded like it could be on the radio. It was definitely a productive, and most of the time, fun collaboration.

JM: Phil has developed a reputation for being eccentric, and perhaps even dangerous. Was there any sign of that back in the early 60’s.

JB: Well, he was always eccentric, definitely. Dangerous? I would hear things, but never around me. Just eccentric. Which I guess we all are to some degree, but he took it to…

[In 2003, Phil was arrested for second-degree murder in the death of Lana Clarkson. A mistrial was declared in 2007. He was convicted in a second trial in 2009, and is currently in prison.]

JM: Describe a typical day at the Brill Building.

JB: I can’t say it was routine. We had an office, and we’d go in and write. It was as simple as that, really, unless we were making demos or in the studio recording. It was writing, demoing, producing, lunch [laughs].

Even then it was obviously classic and fun. In retrospect I wish I had taken movies of it. Some people I know take pictures of everything, I wish I had. It’s hard to know what is going to become historic. But it was definitely filled with characters and it was colorful.

JM: Did it feel like a job?

JB: Oh, no, no, no, no. In fact, there is a saying in the music industry that goes, “it beats working”. It never feels like a job, it never did. Not for a minute. I think people who generally create don’t create for the money, anyway. You create to do it, and if you do it successfully the financial rewards come. But work? No. Absolute fun. Especially in those days, because it was the beginnings of pop music. So it was more than the obvious creativity, we were creating the recording techniques and sounds and styles, not just the songs. I mean, I was very fortunate to be producing as well. Probably producing is more creative fun than songwriting even.

JM: How were your relationships with the other songwriters at the Brill Building? [Other famous Brill Building songwriting teams include Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Carole King and Gerry Goffin, Burt Bacharach and Hal David, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, Neil Sedaka and Howard Greenfield, and Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman.]

JB: Oh, it was nothing but friendly. People talk about a sense of competition. I never felt it, never was aware of it. I guess it was there for some. I was too busy working and having fun, so I never felt a sense of competing with anyone.

JM: Was there at least inspiration from what the other people were producing?

JB: Not for me. It was just all exciting. I didn’t listen to the radio that much, I didn’t really care what anybody else was doing. I really didn’t have time. I’m told I was an inventive writer and producer, and I don’t disagree with that. Because I didn’t have formal training, I didn’t know any rules about anything, really. I was just out of Brooklyn, plunged into the heart of it to do whatever it was that I wanted to do. And the people around me encouraged that.

Very early on, I had success almost immediately. So I never needed to look for inspiration. I looked to and invented what I wanted to do myself. So I never really needed to know what anyone else was doing. Certainly the idea of trying to emulate anyone else’s work was totally crazy, because there was no need to, first of all, [because] I didn’t have the musical ability to do it. I could only create what I could. And I never needed to go beyond myself to have success, so there was no need to really worry about what anyone else was doing.

I prize originality, [the] cutting edge, and like to do things that have never been done, if possible. And it’s hard to do that. It’s rare. I mean, songwriting is all about writing about the human condition, and, more specifically, love. Ninety-nine songs out of a hundred on the charts are going to be about male-female relationships. Or “This Thing Called Love”, as the song title says. Something that nobody’s ever been able to define or figure out. So there’s plenty to do there. And to try to find a new way to say the same old thing is really the songwriter’s challenge. I always say that you’d think they’d have enough love songs by now. But no. I think subliminally people are waiting for this one song to come out that has the answer. But there is none. I might have found a new way to say it two, three times, tops, in all the years, I mean really original, an idea that I’ve never heard expressed before. And it’s rare. They do it in country more often than in pop. That’s really the challenge. To find a new way to say the same old thing.

JM: One of your songs, “Chapel of Love”, has the rare distinction of knocking the Beatles off the top of the charts. Was that more exciting than other times you hit #1?

JB: No, you know, I don’t recall paying attention [to] or reveling in the success. First of all, it was frantic, frantically busy times. And, it wasn’t like you write a song, and make a record, and it comes out and you sit around for year and wait to do the next film or something, you know? It was constant, constant, constant, constant. I mean, Red Bird Records was right in the middle of the sixties, and I’ve been told by people who seem to know these things, that [in terms of] release-to-hits ratio, Red Bird Records is the most successful independent label ever. I guess that includes Motown. It’s hard to believe. But I think there were seventeen releases, and fourteen hits, or something like that, a hit being maybe charted, I’m not really sure. But even if it’s not true, it’s certainly got to be in the top three. And since Red Bird only was around, for maybe under three years, maybe two and change, that’s an awful lot of work, an awful lot of work just on Red Bird. Plus writing with Phil with his product, and other artists as well, plus producing Neil Diamond. I mean just Red Bird, Phil, and Neil Diamond, in the same basic time frame, it was an enormous amount of time.

Plus, other stuff. How about living? In the mid-sixties, there when I was in the Brill Building – I’ve told this story a lot – the New York City police department tried to find me, and I was in New York, in Manhattan, never left, and they couldn’t find me for ten days. And they knew where I lived. That’s how busy I was. When the cops can’t find you.

JM: A Red Bird Records single was “Iko Iko”. Were you the producer on this?

JB: Well, we all did it together.

JM: Could you describe the production of that song?

JB: Well, it’s a strange old song. I think it’s a New Orleans funeral song, actually. I think I’ve heard that. It was a very simple production. I think I’m playing a Jamaican bass box. It’s small, probably two-feet by a foot-and-half, with a hole in it like a guitar, and four, flat metal large prongs nailed over the hole, and you can twang them. I’m playing that as a bass, I’m pretty sure. And I’m playing a screwdriver on a plastic ashtray for rhythm. Those were the days. That’s why I love that stuff, producing back then, it was so handmade, and ultra-creative. It was fun for me. And when you don’t play an instrument it makes sense to bang on ashtrays and whatever. I like to come up with sounds that people hadn’t heard before. It’s ear-catching, it’s just good to do. So it’s a very simple production.

I produced a record with Bobby Bloom in the late sixties, called “Montego Bay”. Bobby and I wrote it in my office. I would be tapping on my metal desk, or whatever it was made of. The side was like a bass drum, and the top was like a snare. So I would be playing the drum on it and he would be playing the guitar, we’d be singing along, and it sounded great. So we went into the studio, I went in with the best band in New York, which were the guys I would use, and I really didn’t like the record at all. It had no personality for an oddball song like it was. I junked the record.

And I found a kid band, and took them in the studio. When I say kids, [I mean] very young, probably never been in a recording studio before. They were kind of nervous, and looking around. It was a little better, it had a little more something. But I junked that record as well.

I said, “Bobby, there’s something wrong, when we’re in my office and I’m banging on the desk and you’re playing the guitar it sounds great, and when I go in the studio it’s just not working”.

So we went in the studio, we hung the mic, got the key on the piano, and we clapped our hands together and sang the song into the mic. You know, recorded vocal hand clap, and overdubbed him and I playing all of the instruments ourselves. And the last thing we did was I peeled off the original hand-clapped vocal, he put a vocal on, and that was it, and it was a hit. But it had that thing. We started with the essence of what was the hit, which is him singing that silly little song.

So, that kind of technique paid off, looking for the right way to do it, to make it happen. Today I think things are a lot less innovative, I should say. It’s still creative, but innovative – there’s not much room for it anymore. Unfortunately.

JM: Could you describe when George “Shadow” Morton first showed up at the Brill Building?

JB: He was an interesting, James Dean like character. You know, he had all these very creative ideas.

JM: Morton claimed in an interview that he was primarily responsible for the song “Leader of the Pack”…

JB: Mmm, hmm.

JM: …and even said that he didn’t think Ellie had even heard the song until it came out.

JB: God, somebody should ask him who produced it. I don’t even know what to say. It’s definitely mostly his vision, for sure. Unfortunately as a songwriter he was limited to that kind of song. That’s his thing, which is a good thing. But… wow.

JM: I read a response that Ellie had [to his claims], and it was quite similar. She was surprised that he would characterize things that way.

JB: So many people taking credit for lots of stuff over the years, but that particular song had so many people around it. People claim they produced it? God.

JM: Did a young Billy Joel really play piano on any Shangri-La’s tracks?

JB: No, not that I ever heard. Not that I know of. Let’s put it that way.

JM: I have a few questions about “River Deep, Mountain High”. You wrote that with Phil and Ellie…

JB: River Deep, Mountain High was probably the only song we wrote with Phil that was really aimed at one artist, a specific artist. All the rest, you know, any one of his artists could have done any one of his songs. But we wrote that for Tina. It’s probably the rangiest of all of the songs.

JM: How would you characterize what each of you individually brought to the song? Did you each write specific parts?

JB: I probably wrote, maybe all of the lyrics. I’ll leave room there – I wrote 95% of the lyrics, I don’t know, but definitely that was my first responsibility. When you write with me, I’m going to walk around the room singing stuff, so there is a lot of my melody in there. But not one chord. So that’s it.

JM: The production of the song has been characterized different ways. Some people think it is the ultimate “Wall of Sound” song, other people think that it’s overwhelming. How do you feel about the production of the song?

JB: The song was created for Tina. I think the song is different from all the [other] songs we wrote. And I think the record is appropriately different. If it was the same production, identical to all the other records, that wouldn’t seem logical. I think he came to the song. The song was definitely a more elevated song, lyrically, chordally, melodically, subject matter. I think it’s a better song, in the classic songwriter sense. So he made a record that was appropriate to the song. That’s what I think. I don’t think it is overwhelming. I mean, overwhelming? People would hear it and can’t breathe? It was innovative, you never heard of anything like that before. But that’s what makes it classic. That’s what I was talking about before: do something new. Same old is just that: same old.

JM: The song didn’t do well in the US, and Phil ended up essentially leaving music for a short time because of the poor reception. Did you ever have a similar experience with that song or something else where you thought something was great and it didn’t take off?

JB: No. No. Mmm, mmm. I was just thrilled in general. So if something was a hit it was a hit, if it wasn’t, it wasn’t. I never paid really any attention to that part of it.

JM: Earlier you mentioned Neil Diamond. Could you describe how you met him?

JB: Ellie told me she heard some singer in a demo studio. We wanted to sign him to Red Bird Records, and Jerry [Leiber] and Mike [Stoller] didn’t really get it, get him. They just didn’t hear it the same way we did.

My best friend at the time was Bert Burns, who had Bang Records, so we took him over there and cut him for Bert on Bang. He was, in the second year, the up-and-coming male artist on the Billboard charts, and in the third year he was the #1 male artist in the world.

JM: You produced some of his earliest albums…

JB: All of them.

JM: What are your memories of those sessions?

JB: The main thing about recording someone with songs that I didn’t write, is just that. And his songs were kind of sophisticated, and very much him. If I just heard Neil as a singer, and he couldn’t write, I don’t know if I would have been as excited. It’s not like he’s “Mr. Pipes”. He sings his songs. They say nobody sings a song like the writer, and he’s a perfect example of that. That to me is where the excitement and the value was. Not only was he good at singing the songs he had, but he was obviously was going to keep supplying himself, which is a really hard thing to do, to keep coming up with hits for any given artist. So that to me was the underlying value, where you’re going to have an endless, exclusive well of material that would keep coming. I saw no reason why it wouldn’t. He was very prolific, and very bright, and talented.

When I produce, it’s presenting a song. I say that the song in the record is like a stone in a ring. The better the stone, the simpler the setting. You try to present the song interestingly, [with] ear- catching arrangements. To me, if you don’t have a song, why go in the studio? And if you have a song, don’t bury it, don’t overproduce it.

The records made with him are more sophisticated. It’s just like the record Phil made with “River Deep, Mountain High”. I can’t make the same record with “Kentucky Woman”, or “Girl, You’ll Be A Woman Soon”, or any of Neil’s songs that I would make with The Dixie Cups singing “Chapel of Love”. It’s a whole different… you can’t do either production with either song, you can’t cross them. So you bring the production to the song. That’s why Neil’s records are more sophisticated, less pop. Even though they’re pop, but they’re, I don’t know… more sophisticated is the word that comes to mind. Because that’s what it demands.

I had a conversation with him two weeks ago. I’d love to see him perform with just him and his guitar, sitting on a stool. I think he would pack the place and kill them. He goes out with six trucks and 80 people, or whatever the hell it is, and puts on a fantastic show. He’s been doing it forever, and his fan base is so solid. But I said, “Neil, it’s not like you run around the stage, and carry on. You basically stand there and sing your songs, play your guitar, and all this other stuff is around you. But it’s still you singing the songs. That’s what I was excited about, and that’s what I believe they come to hear. I think if you stripped all that stuff away and sat on a stool and sang your songs with an acoustic guitar, people might even love it more.” Because they really will hear the essence of what I think is… all entertainment is about creating emotion, and I think the stuff around him is a very small part of what that emotion that he creates is. But it’s a big part of the budget. [laughs] So I think he would create almost the same emotion, but actually have a simpler life and make a hell of a lot more money.

JM: Was he receptive to this idea?

JB: Well, he’s going on tour, and he said when he comes back let’s talk about it. He thinks about it from time to time. I’m not the first probably to suggest it, but I might be able to make him comfortable doing it.

JM: Speaking of Neil Diamond, he wrote “I’m A Believer” which became a huge hit for The Monkees, and a song you produced. Can you describe the production of that? Were The Monkees involved to a great extent?

JB: No. I mean The Monkees, the whole situation with The Monkees is probably a mini-film. A lot of… not a lot… personalities, egos…

[For] my assignment, as I recall, Don Kirshner called me and said, we’ve got the hottest show on TV for kids. “Last Train to Clarksville” at the time hadn’t sold a million. He asked if I would like to take a shot at the next single, and continue to produce them. I did, and Neil had “I’m A Believer”. As I recall, I don’t think he was anxious to record it. I think by that time he was into more sophisticated things. I’m not totally clear why. I mean, obviously if he wanted to record it, he would have. Record of the Year, you know?

I made the basic track, which is drums, bass, piano, guitar, in New York. Either Neil or myself, I’m not sure, did a vocal on it so the kids could learn it. Flew out to California to meet The Monkees. Met them for the first time. You know, Don Kirshner, some other people, and the four guys. That’s the first time I met them, and played the simple demo, vocal way out front so they could hear it. They’d never heard the song. “This is going to be one of the songs we’re going to record, guys, and one we think could be a hit.”

Many times I say “as I recall”, but this I definitely recall, because it was burned in. I play the record. Everybody was, you know, duly polite. I mean, I don’t think anybody said it’s a smash or isn’t a smash. You know, who knew? You go by instinct. Everyone was, “Hey cool”, everything positive. Mike Nesmith, who was the only one who came with a girl [laughs], he’s slouched down on the couch – it’s very clear in my mind – and he says, “I’m a producer, too, and that ain’t no hit.” It was, like, “ooo”, everybody in the room was like “umm, err”. So, as I am wont to do, I went to some humor, and said, “Well, Mike, I understand, but you gotta picture it with strings and horns”, which I thought was obviously a joke because who the hell is going to put strings and horns on that. I mean you could, but everyone else in the room understood that. He thought, and he said, “well, maybe with strings and horns”. Everybody started laughing, and he was so embarrassed, he got totally pissed off. Anyway, that was the beginning of our relationship. When we went in the studio, he was so disruptive, I ended up kicking him out of the studio.

You know, they we’re hired. He got the job because of the woolen hat. They kind of remembered him – it was a good idea he had to wear the woolen hat to the auditions. But, it’s not like he was really good at anything, in my opinion. He thinks he is some kind of genius, but I don’t. He probably has the same opinion of me. So that kind of validates me. But, he was just totally disruptive. He wanted to control everything, and eventually he did, got Kirshner out, and took over… and everything went downhill from there. Never had another hit. Because he can’t write, he can’t produce and he can’t play, and he can’t sing… When I say he can’t, not at the level that you need to be able to. Anybody can sing, anybody can write a song, anybody can go in a studio and produce. You really can. It’s not brain surgery. But considering it was one of the hottest acts in the world that he had to work with, you’d think he would be able to continue what was happening.

Have I vented enough here? I think so.

Anyway, that was my experience with The Monkees. And they are all nice people, except for him. Him, I never really got along with.

JM: I’ve read that you were surprised when the song “Hanky Panky” become a hit for Tommy James and the Shondells. It’s a very catchy song – why were you surprised?

JB: Well, we wrote the song for a B-side of a record of a group we were a part of, The Raindrops. At the time there were ten cuts in an album, and I always say, people hear our single, and they buy the album, they already have two cuts of the album if they bought the single, because the

B-side is always on the album. So they are really buying eight new cuts.

We had time, we recorded what we needed to record in two hours, [and] we had an hour left. When you book a band it’s three hours. So we kind of wrote that on the spot – that’s my recollection [laughs]. That’s why it’s so simple and silly.

I said, let’s just write something, record it, put it on the B-side of the next single, so anybody buys the album, they get nine new cuts. Tommy James bought the single, flipped it, heard that, and cut it. It wasn’t like I was surprised, so much as, “Hey, that’s cool.” I’m never surprised at something being a hit or not. It isn’t really a judgment. So I can’t say I was surprised.

JM: Your song “Sugar, Sugar” has been described as the “perfect pop song”…

JB: I didn’t hear that.

JM: How did you do it? What’s the story? How did you put it together?

JB: I wrote that with Andy Kim, and recorded it in RCA, Manhattan. That track took, as I recall, at least two hours to cut, with just the band, to get that groove right. I could not get that band, mainly the drummer, to just get the groove the way I [wanted]. Finally, finally, finally got it, and overdubbed everything on it. I think I’m playing the organ, “da da da da da daa”.

JM: Which I think makes the song.

JB: Well, you know what, it’s easier for me sometimes to play something – that I’m capable of, I mean on the keyboard I can do that, not on the guitar – than to try to get a musician to feel it exactly the way I felt it. Which is basically called “behind the beat”, “layin’ way back, layin’ back on it”, as opposed to “on top of the beat” or “on the beat”. So I just did it myself, it was just so much easier.

I learned that even mixing records, instead of saying to an engineer in the middle of the mix, saying “more organ!” I like to sit at the board, move the knobs myself. Because how much is “more”, you know?

It was a fun record to make. For me as a producer I particularly like the fade, where a lot of elements come together from the song, and there’s all kind of stuff going on. It’s almost like a whole new record. Even though the record is interesting, entertaining, and alive up until there, it goes up a notch. And I think that it worked out really well. It’s hard to get that done. I think that’s part of what contribute to its success.

JM: One thing that I find interesting about that song, and all of the Archies songs, is that Ron Dante, who sang the vocals, had written a parody of “Leader of the Pack” called “Leader of the Laundromat”. He was even sued for that song. Then he came back into your orbit and sang those songs. How did that come about?

JB: I really don’t know. I know that in looking for the right voice I chose him. But I really don’t remember how.

JM: Obviously there was no bad blood.

JB: Oh no. Those were pretty loose days. I don’t know if anybody knew all the rules. So it’s not like I sued him. The publishers said, “you can’t do that”. You can’t take a song and change the words and put it out as if you wrote a new song. I don’t even know if it was a lawsuit. I think they went, “Yeah, duh, OK” and settled it, and figured it out. But it was certainly nothing that I would take personally.

JM: At the time, songs like “Sugar Sugar” and all of bubblegum pop wasn’t highly regarded by the critics. It has since been more appreciated by critics because they recognize that these are catchy songs put together very well. At the time did it bother you?

JB: No, again I wasn’t paying all that much attention. I think a lot of that happens because the press wants something to write about. As I understand it, the word “bubblegum” came from a record called “Yummy, Yummy, Yummy, I Got Love In My Tummy” by the 1910 Fruit Gum Company. So they’re just begging to be labeled “bubblegum”. When something is labeled everybody picks up on it and it’s kind of fun and the press gets on it. But I think basically it’s the press not being aware of the very simple fact that these songs were not meant to entertain them, or any other adult. It would be like if movie reviewers were to review a cartoon as if it was an adult film, intended to entertain adults, and say, “Oh, this Porky Pig character, first of all he’s not wearing any underwear, and he only has four fingers. How ridiculous is that. And the plot, oh my God, it’s so simple and stupid, and it’s so short. I mean, my goodness.” It’s meant for kids, you idiot. Why don’t review it like that? That’s the basic fallacy of all that. These songs were created for single-digit-age kids. At the time, “Sugar Sugar” was created for preschoolers. The Archies cartoon show was on Saturday morning TV for preschoolers, not even kindergarten, you know, K-3. [With emphasis] Pre-schoolers. Four year [olds] and younger. That was my audience. And to judge it, even for teenagers?

It was record of the year, sold 11 million copies, so obviously it had an appeal to more than preschoolers. Because somebody went to the store to buy it, not the preschoolers. So the whole idea of judging out of its intended market, judging it up, is erroneous on the part of the critic. It’s that simple. It’s that simple.

JM: In 1971, you produced an album for Dusty Springfield which didn’t come out at the time. What happened?

JB: Well, we took a long time. Jerry Wexler and Ahmet Ertegun owned the [Atlantic] label, and in talking to Jerry at one point, he said, “Why don’t you cut somebody on Atlantic, make a record here. Who do you want?” And there were two artists that interested me, and that was Wilson Pickett and Dusty Springfield. Anyway, he said that Wilson has a production situation, let me call Dusty. He called her in London, and she said that might be interesting. She came over, I had my staff of writers and put the word out and got songs. By the time the album was almost done, [laughs] her contract was up with Atlantic, and I don’t know why but I don’t think it was going to be renewed. So it all kind of just fizzled away. It probably wasn’t the best thing I ever recorded, and certainly not the best thing she ever recorded. You know, a lot of people like it now, but for me what came out of it mostly was a continuing friendship with Dusty. She was a great lady. And that’s the story.

JM: But it did come out eventually as bonus tracks on “Dusty in Memphis”.

JB: After so many years it becomes history, you know, and interesting to people.

JM: Could you describe your involvement with Van Morrison’s debut album?

JB: Van was on Bert Berns’ label, who was my best friend at the time. I was always at my office or he would be in my office, and we’d be taking motorcycle trips and playing pool, just stuff that best friends would be doing. My favorite bit of record trivia is on the fade of “Brown Eyed Girl”, it’s me singing not Van Morrison. I like to tell that story. That’s me singing “Sha la la la la la la…” That’s me singing, because he had finished the record, except for that. He went back to Ireland, and Bert wanted to put the record out.

I used to imitate people at the time. Once you know it’s me singing you realize that it doesn’t sound that much like him. So I went in and filled in that part, and probably played tambourine on most of his record.

He was an interesting guy. He had some strange songs at the beginning. I remember “TB Sheets” was one of them. It’s about his wife who had tuberculosis, whoa, the subject matter.

JM: It’s not “Sugar Sugar”.

JB: You know, my job is not to write about tuberculosis. [pauses, then laughs].

JM: About the song “Brown Eyed Girl”, I think the rhythm guitar part that Hugh McCracken plays is one of the all-time high points of rhythm guitar. I understand that he worked on some songs with you.

JB: On yeah. You know, there were a few great [session] guitar players in town. Al Gorgonny, Vinnie Bell, Hugh McCracken. You know the three or four great guitar players, the three or four great everything, each of the basic instruments. You’re going to do a session, you might have your favorite but if he’s booked one of the other guys is going to do just fine. Hugh was one of the youngest and definitely one of the most talented, but they were all great. And you get a little bit different style. They all bring themselves to the session, to the song. No one was looking at the clock, and no one was bored. It was exciting, exciting times. When you’re one of the top musicians, you’re probably always booked with some of the top recordmakers, so your chances of hearing your work on the radio were greater than some of the lesser known musicians. So that’s always exciting, when you know that the public is actually going to get to hear what you’re doing.

JM: It’s interesting that if you were to ask a guitarist who is their favorite guitarist, these names probably would not come up.

JB: Well, these people never really performed as artists, so unless you’re a record-phile you’re not going to know these names. They might be on the back of the albums, maybe not. These guys would do three sessions a day, 10:00-1:00, 2:00-5:00, 7:00-10:00. Three sessions a day. You can get burned out pretty good, but I think the times were so exciting that each session was unique and fun. I mean, historically rock and roll, modern pop, all started in 1955. As far as I know that’s the cornerstone date, because Alan Freed the disk jockey said the words “rock and roll” on the radio for the first time. If it started in 1955, and the drum and the guitar came out of the south and built up slowly, it didn’t really get rolling until the sixties. And that’s when these guys really started working. I call it Kitty Hawk, we were all the Wright Brothers. It was real exciting times, no one was bored yet. It was real fun. Not only that, but they guys were making good money, too. So it was exciting on many levels.

JM: In 1973, Phil Spector produced the “Rock ‘N’ Roll” album for John Lennon. Were you involved at all?

JB: I was there a lot. My offices were at A&M Records where it was recorded. I would hang around and drop in and say hello. I got to know John a little bit. But that’s about it.

JM: Those sessions have become legendary for people being drunk in the studio, Phil Spector firing a gun, and so on.

JB: I don’t recall any of that. I certainly wasn’t there for any of that.

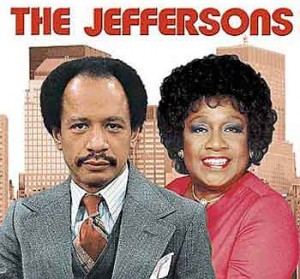

JM: What did you contribute to the theme song for “The Jeffersons”?

JB: Oh, I wrote the whole thing. Well, I co-wrote it, but it was mainly me, quite frankly. I wrote it with Janet DuBois, who was one of the actors on one of the other Norman Lear shows. She contributed to some of the lyric, and I got her to sing on it. She’s doing the lead vocal. It was the first and last time I think she ever recorded. She brought such a unique quality to it. I produced it, and probably [did] hand clapping and playing some of the stuff on it. But it’s very simple.

Again when you’re doing something you don’t know what the future is going to be. But that one has turned out to be, like, Top Ten whenever there’s “What’s Your Favorite TV Theme Song”. That one and “One Day at a Time” end up high on the list. But “The Jeffersons” definitely. That’s probably my favorite, that just kind of works.

JM: Did you know about what the show was going to be about when you wrote the song?

JB: Oh, sure. Norman Lear, who is one of my heroes – a great guy, a great creative guy [who] lets people do what they want to do and doesn’t ego-out at all – he would give me the script and I’d read it and then I’d go to the first taping. I’d have ideas before the taping. But then I’d watch it, finish up, and play it for him, and record it. But it’s all influenced by [the show].

You know, writing theme songs – I love doing that. Because assignment writing, it’s fun. You have, first of all, 45 seconds, and so many parameters, besides the time parameter, that it’s fun to nail those. It has to be classic, and it has to set the mood. I think that “The Jeffersons” is one of the first theme songs that didn’t have the name of the show [in it]. I asked Norman if I could not have to say “The Jeffersons” – it’s pretty restrictive. Typical Norman, he said “sure!” You can always undo something, he can always say “no” once he hears it. But he’s that kind of person, totally open-minded. Where is it written that it has to say “The Jeffersons”? You know what show you’re watching. It worked out well.

JM: I have a few questions about songwriting, some specific to your songs and some more general. I’m sure you get this all the time… Where did the phrases “Do Wah Diddy Diddy” and “Da Doo Ron Ron” come from?

JB: I don’t know if they came from anywhere, except, you know, some weird creative place. But how or why? I don’t know, I just don’t know. I mean I grew up with “three little fishes in the itty-bitty pool” and “abba-dabba-dabba-dabba-dabba-dabba-dabba said the monkey”, so I’ve heard silly things and catch phrases. I suppose that’s all in my psyche and part of it. But I really can’t say that I know. That it was on purpose? I’ve heard I put that in temporarily until I thought of words. No, I don’t do that. I think it was done on purpose in that this will be the title, and this will… As I say, it’s not brain surgery. It’s not like you sit down and calculate and figure things out. You’re writing a song… for young minds.

JM: Were there any songs that were particularly easy to write, they just came to you?

JB: I don’t remember any of them being hard. The only song I know how long it took to write was the song called “I Honestly Love You”, Olivia Newton John. I wrote that with Peter Allen. We wrote that in six hours: three hours one afternoon, three hours the next afternoon.

That’s the only one I know how long it took.

JM: Was that the longest, would you say?

JB: Probably. It might very well be.

JM: What advice would you give to an aspiring songwriter?

JB: [long pause] Have a clear vision of what you’re doing, why you’re doing it. All show-biz, all entertainment has one thing in common, whether it’s film, TV, writing a novel, a song, or a script, painting, anything. It’s all about creating emotion. There’s an old adage that if you leave them like you found them, you blew it. So it’s all about creating emotion, and a songwriter needs to understand that as well. That’s why people want to buy, and own I should say, the thing that you’re presenting, because it creates an emotion. Otherwise why would they want it? I think that’s fact #1.

You’re communicating. You could even say songs to some degree are a little like greeting cards. People buy them to express something to someone else that they can’t make up themselves. So it’s all about communication and creating emotion. If you’re writing strictly for yourself, and the lyrics are obtuse and unavailable and people don’t know what the hell you’re talking about, then you sure are limiting your ability to create emotion. So write those songs, get that stuff out, that’s fine. But if you want to make a living at it, you need to write songs that are commercial. Commercial is a good word. There is nobody in show business that is not trying to be commercial. I don’t care how obscure and weird they are, they want to sell, which is commercial. Pop is short for “popular”, and that’s the idea. If you’re not looking to make a career of it, it doesn’t matter. Write songs, that’s great. Play them for family and friends, and whatever, that’s beautiful, there’s nothing wrong with that.

But your question, I think, is aimed at people that want to make a living at it, which is tough these days. I’m very thankful that when I came into the industry the songs were more valued than they are today. Today record companies are interested in things other than the songs, a lot of the time. And the artists who are writing their own songs, they’re having hits, maybe not based on the song all the time, [instead] on the rhythm and the haircut and the tattoo and the weirdness and the publicity. Which is different from what it was back then. In my heyday, it was certainly more based on radio play, what it sounded like. The E Channel didn’t exist, and TV wasn’t such a source of entertainment as it is today. It was more about the audio than it is today, which is a lot to do with the visual.

So the advice would be to basically create emotion, keep it simple, keep it clear. When you’re trying to get to somebody in the industry, take the three to five best songs, most commercial songs, most valuable songs, and put them on a disk. Don’t present 25 songs. You don’t have 25 hits, you just don’t. Take the best five, even if you have 25 smashes. Take the best five. Get that to whoever you can. And the emotion you want to bring out in anyone that you’re pitching to is greed. No one is going to do you any favors. Greed is a healthy word, whether it’s a music publisher, or a recording artist, or an A&R person at a label, or a record producer. You want them to want the material. No one is going to do you any favors, record it just because. If it’s a relative, perhaps. But otherwise, as it should be, they have to hear something that is going to make them look good, make them a success. So keep that in mind.

The other hint would be, sometimes you start a song and you write the first verse and you write the chorus, and then you get to the second verse and you can’t come up with the second verse. It could be that you’ve already written it. You take the first verse, make it the second verse, and then write the first verse [as] pre-story, set-up. That will free you up. So in other words, the beginning, middle, and end, I mean you might have already written the middle. And if you have, and you put it at the beginning, you’re messed up. Because then you’re going to write the ending for the middle, and you’ll have no ending. So I find that, for myself, that works. Because basically if you have an idea for a song you’ll write the core idea instantly, and the core, which is represented in the chorus usually too, but story-wise many times it’s overrepresented in the first verse. So you can take a look at that. That might be a good hint for songwriters in general.

JM: Do you think it is important to write with other people?

JB: If you are a complete songwriter, you can write the chords, the melody, and the words – there are three parts to a song, not two – then there’s no need to. But it’s fun, and it’s something that everyone should experiment with. If you meet someone and they have a particularly interesting angle on one of those three parts, why not? Why not co-write and see what happens?

JM: Are there any of your songs that you feel should have been hits but weren’t?

JB: No. No.

JM: Are there any cover versions [of your songs] that you’re particularly fond of?

JB: [pause] I wrote a song called “Walkin’ in the Sun”, which was inspired by an incident with my father, who was blind. I’ve told the story a lot. When I was a teenager, as I said my father was blind. He was an insurance salesman. I went to Manhattan with him from Brooklyn where we lived. It was the end of the day, and the sun was on an angle, and we walked to the subway to go home. It was chilly, and we discussed that, and he said “is the sun out across the street?” And I looked and sure enough it was, because of the angle of the tall buildings, and so on. He said, “well, let’s cross over, we’ll walk on that side.” I didn’t think of it, he did.

So fade out, fade in, many years later I’m writing songs for myself. I was going to make an album, which I did, never released it though, for A&M Records. There’s a song saying basically, “I’ve been down, so I recognize up.” The punchline is, even a blind man can tell when he’s walking in the sun. A lot of people have recorded this song, and one of the classic R&B artists, Percy Sledge, did just an amazing record of it.

My first major record, Sam Cooke recorded a song called “Teenage Sonata” in 1960. That was a big thrill. That’s not a cover – that was the original record.

Otherwise, nothing jumps out.

JM: Who are your favorite songwriters?

JB: I think Paul Simon would be #1, just because he does it himself. He doesn’t need a co-writer. A lot of songwriters, and it’s not any kind of a negative statement, but they write in a certain style, and that’s their style and they write, not really narrow, but they write them. But Paul Simon can write a variety of styles of songs, and they’re all so well-crafted. And he can record them himself. He’s a self-contained hit machine. So he’s #1 for me.

And then there’s other obvious guys who write themselves, like Billy Joel and Jim Webb, as single songwriters.

There’s many obvious co-writers, duos: Mann and Weil, Goffin and King, you know, the usual suspects. But when you say “who’s my favorite songwriters”, I think of individuals.

JM: I understand that Paul Simon was hanging around the Brill Building back in the day. Did you ever interact with him back then?

JB: Uh huh. I knew him before he was Paul Simon. He was part of a group called Tom and Jerry. It’s all documented somewhere.

JM: Apparently when Paul Simon writes lyrics, he might spend years getting it just right. This is a contrast to your songs which were typically written relatively quickly.

JB: Well, a lot of my songs are really quite similar. The word “walk” is in the first line of at least four songs I wrote. So I mean, I guess that’s a bit of a put down.

JM: But I think that’s underselling yourself.

JB: To tell you the truth, I didn’t have a year. It was all happening really quickly. Like now.

JM: I should congratulate you – you recently turned 70. Are you still writing songs?

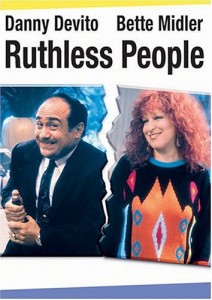

JB: Oh sure, all the time. I’m writing a musical based on a movie called “Ruthless People”. We’re calling it “Ruthless”. The stageplay is being written by the screenwriter. I’m writing it with Jed Leiber, who is an absolute genius. We’re having the best time. It was such a dark comedy, I don’t know if you remember the movie – Bette Midler and Danny DeVito. It’s interesting to write subject matter like I’ve never had the chance to write before.

JM: When do you expect that to be done?

JB: We’re doing it for ourselves, so “easy taskmasters”, you know? We’re going to play six songs and show the stageplay to Disney in the next couple of months, or so. They have the right to see it first because they made the movie. And we’ll go from there.

JM: Have you ever heard the version of “River Deep, Mountain High” by The Saints? [I give him the “(I’m) Stranded” CD, which has this song as a bonus track]

JB: I’ll listen and let you know.

JM: You might be thinking, “how do you top what Tina Turner did?”

JB: I don’t think you try to top it, you should do it your way. Most of the time they just kind of do the same arrangement with a different vocal, which is not very creative. I would say that a group like this, not even really knowing the group, would definitely come up with something different.

[Looks at CD booklet] What ever happened to smiling? When was the last time you saw a group that smiled? It ended with the Beatles. Everybody takes pictures like, “OK, let’s get this over with, I hate being here.” [laughs]

JM: Well, that was part of the image. This was 1977.

JB: Oh, is it that old? Even today they don’t smile. That’s why this group looks so modern. I think The Stones were the first group that didn’t dress the same. The Beatles all had the same little outfits, little ties. The Stones all wore different stuff.

JB [by email, later]:

Ummmmm…….. let’s say – The Saints’ record is not my favorite version, but punk is not my favorite music either.

Terrific writeup on a terrific songwriter. Great job! Your interview with Jeff Barry is entertaining, interesting, comprehensive and educational. Truly illustrates the man behind the music, and the genius behind the song. You asked some wonderful questions and gave us great insight into this legendary Brill Building composer and producer. Thank you!

Typical interviews with songwriting icons usually have a “been there, read it before” quality. I’m rather hardcore, and came to this site expecting the usual. What a surprise! This piece is flat out excellent, and has given me a whole new perspective on Jeff Barry. Thoroughly enjoyed reading it from start to finish.

Oh my god! those comments about Nesmith sound like a big bunch of sour grapes. I can understand not liking him, but the man’s talent was undeniable, even at that time. The songs he wrote and produced on the first album – “Sweet Young Thing” and “Papa Gene’s Blues” – are markedly different from anything being recorded at that time

You should definitely investigate the Steed label. Jeff Barry rarely talks about it, but he owned this label between 1967 and ’71. He produced every release, and there are many great records including hits by Andy Kim, Robin McNamara and a psychedelic Rock band called The Illusion.

BTW, Ron Dante did not write “Leader Of The Laundromat”, he only sang on the record along with Danny Jordan (the lead singer) and Tommy Wynn.