When you think of Jethro Tull, the first thing you probably think of is the guy with the flute. But pretty soon you also think of all those cool electric guitar parts and sounds, and when you think of that you’re thinking of Martin Barre.

Barre joined Jethro Tull in time for their 1969 album Stand Up, which steered the band away from its blues origins to an new sound which incorporated elements of English folk music. Other classic albums followed: the harder rockin’ Benefit, the multiplatinum Aqualung, the prog rock concept album masterpieces Thick as a Brick and A Passion Play, and many more. Barre’s tenure with Jethro Tull lasted until 2012, and since then he has focused on a solo career. His most recent album is 2015’s fantastic Back to Steel.

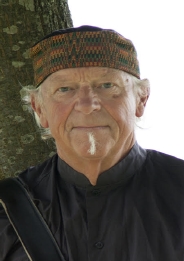

This interview was for Martin Barre’s concert at SOhO in Santa Barbara, California on 9/13/17. It was done by phone on 8/9/17. (Martin Webb photo)

Jeff Moehlis: I’m happy to hear that you’re recording, because that must mean that something new is coming out.

Martin Barre: It is indeed. It’s an interesting process. I always find you’re on a knife’s edge. One minute you think it’s amazing, the next minute you’re full of self-doubt and self-loathing [laughs]. I’m sure it’s going to be absolutely fine.

JM: What can people look forward at the upcoming concert?

MB: It’s a new band, it’s fresh. The musicians have got lots of motivation and energy. We’ve made the music really revitalized. There’s nothing retro or 70’s or 80’s about what we do. It’s sort of a blues band, a rock band – really dynamic – and we make everything we do really exciting. We take material from the Tull catalog, but we’ve sort of reinjected it with a lot of new energy, and we’ve re-examined it and taken it apart and reconstructed it. Essentially, we love playing, and we have a great time touring and playing to audiences.

JM: Your latest album Back to Steel came out last year. I have a copy of it right here, and I think it’s great. How did that album come together?

MB: I’ve done about eight solo albums, and they’re fairly low-key because historically when Tull was on the road I rarely got much time off. And then when I found I had like two or three months free I’d get in the studio and start writing and recording. Mainly it was instrumental, but I always gave it a hundred percent. I took it very seriously, but I knew in the back of my mind that it was a bit of a detour, and at the end of it I was back to Tull, back to touring, back to making a living the way that I have done for fifty years. But now, it’s really vital that the music I write, the music I perform, is mine, and I’m looking for an identity that is really me. I’m not here to sort of repackage Jethro Tull – I’m here to promote a new band, and it just so happens that I’m in it. So it’s really important that my music writing and the albums that I’m producing become part of what we do live. I want people to enjoy what we do with the Tull music, hand in hand with what I’m doing in my writing. They seem to blend. The audiences over the last six years – you know, I’ve been solo for six years – they’ve really enjoyed everything we do. It’s really good, because it’s important to me to have my own identity.

JM: For the song “Back to Steel”, I feel like there’s a story there. What’s the story behind that song?

MB: There is. I went to Nashville to buy an old jazz guitar. I’m a typical musician – I love guitars, and I’m always sort of trawling the internet trying to find quirky stuff, and I found this guitar. It wasn’t expensive, and I drove from where my son lives in Mississippi up to Nashville and I got this guitar, a beautiful thing. And I stopped on the way back in a motel just to break the journey up, and I spent the whole night playing this guitar, because it was such a beautiful thing. It was just me in motel room, and a guitar. I just thought, this is essentially what I do. It’s me, a piece of wood, some wire strings – it’s such a very earthy thing, a tangible thing that you’re connected to music through. I just sort of fantasized about who had played this guitar, how they’d looked after it, what sort of music they’d played on it. And that’s how the song came about, because it’s sort of back to wood, frets, strings [laughs]. It’s back to basics.

JM: On that album you also have a great – and somewhat surprising – arrangement of “Eleanor Rigby”. What inspired you to tackle that song, and where did that arrangement come from?

MB: Well, I’m a big Beatles fan, and I worked with Paul McCartney, and I was lucky enough to meet all the Beatles. I’ve always been a fan, and I think since Sgt. Pepper they’ve become such an important musical entity historically. I just wanted to have fun. A lot of people use the Beatles’ material, like Jeff Beck playing “A Day in the Life”. It’s such a beautiful piece of music. And I just think the Beatles’ music – the songwriting, the melody, the chords, the composition – is so special. I like to enjoy and have fun with it. We’ve been playing this for a couple of years, and the audiences love to hear “Eleanor Rigby”. Now we do a version of “She’s So Heavy”. We do sort of a blues, really loud version of it. The music’s timeless. You know, you can change it, you can adapt to it, you can put your own stamp on it and it will always be great music.

JM: Of course, also on that album you have a cover of “Skating Away”, which I think is also great. It’s an interesting arrangement. What brought you back to that song?

MB: I’m sort of expected to represent Jethro Tull when I do gigs, for obvious reasons, and I don’t just want to go through a catalog and pluck songs out of the catalog and just reel them off note for note. So I take a lot of time thinking about how I’m going to represent this music. Sometimes some of the Tull songs will adapt to looking in a different way. Sometimes we do “Fat Man”, a we do a heavy, bluesy version of it, and it works really, really good. Some Tull songs I leave alone, because they don’t need adapting, they work as they were written and don’t need to be changed. But other ones you can have a bit of fun with, and the audience retains the quality of the song and the intensity, but it’s fresh and sort of a new take on it, and the audiences really enjoy it.

JM: You first toured the US with Jethro Tull almost fifty years ago. Are there any stories from that first US tour that you’re willing to share? Or is it better left unspoken?

MB: [laughs] Well, the joke would be that there’s some amazing stories, but because it was fifty year ago I’ve forgotten them all. I loved being in America. I could tell you funny stories, and they’re like everybody else’s stories. They usually involve crazy musicians, crazy bands, groupies, crazy concerts. We went through all of that like everybody else did. We played with Led Zeppelin, we played with Beefheart, Zappa, the Grateful Dead. We’ve sort of done everything, and had an amazing time. I loved every minute, and crazy things happened. You’ll probably have to wait for the book. I just loved every minute.

The very first tour we did of America, we started in New York and went up to Boston – it was snowing. We went over to Detroit, and it was all amazing for us because we’d never been to The States before. And then eventually, three months later, we ended up in San Francisco and L.A. It was incredible. It was almost a different planet for some guys from the U.K. I can remember the smell. I can remember the early days on the West Coast better than I can remember last year, because it made such a huge impact on me. I just love the culture. I took to the American culture, and I even married an American lady – I’m still married to her. I’m sort of an honorary American.

JM: Around that time was your first recordings with Jethro Tull, for the Stand Up album. Where was your mind at when you started that? You were the new guy in the band.

MB: Luckily, I went through the difficult period in England, because I joined in England and we did maybe a dozen shows in the English blues clubs where they were expecting a blues band. Jethro Tull were a blues band, and I joined – what happened to the blues? Where is it? Because we were playing music from Stand Up, and they didn’t like it. At first, they really didn’t like what they heard. They wanted the blues. They wanted 12-bar blues, slide guitar, “Dust My Broom”. It was a very difficult period. I felt alienated. The rest of the guys were really wondering if we were doing the right thing. Ian, who was writing all this new music, he put his career on the line, because Jethro Tull were a blues band, and their reputation was solely based on that. We were completely turning our backs on the blues scene in England, and coming up with new music. I mean, it was very intelligent and the right thing to do, but it wasn’t an overnight success. People had to get to know the music.

But by the time we came to America, we’d sort of settled into what Jethro Tull was going to do. And we saw how it was going to work, so we had a lot more confidence. So therefore for me, I always see Jethro Tull in America as the beginning of Jethro Tull’s career. It was new music, a new band, and a new country.

JM: The next album was Benefit. How did you approach that album differently from how you approached Stand Up? I should tell you that Benefit is one of my favorites.

MB: It is mine. We play a lot of songs from Benefit because I really love it. Stand Up was nervous, a new direction, sort of treading on thin ice and wondering what to do and how people would like it. And people did like it – it was a big album. Benefit – we were back in the studio and we knew what to do. So we had lots of confidence and we could sit back and enjoy it. The nervousness had gone, the trepidation had gone. We were super confident, and it was the same sort of direction, we really felt at ease. It was a very, very positive album because of that.

JM: It has one of my all-time favorite Jethro Tull songs, “To Cry You a Song”, which has such a cool guitar riff in it.

MB: Yes, I’ll be playing that in Santa Barbara.

JM: How did that particular song come together?

MB: Ian would write a riff, he’d write some chord sequences. We’d sit in the studio and play around with it, we’d have a jam. It was like all bands in those days. It was all off the cuff, and very little was planned and arranged until you actually got in the studio and figured out what you were going to do. That’s why it had that sort of dynamic, that freshness, that sort of innovation about it, because it was born of naivete, really. Bands really didn’t sit down and pre-produce. Pre-production was a phrase that hadn’t been invented. It was great, exciting, because nobody knew from one day to the next what we were going to do. So it was four guys – or five with John Evans – off in the studio: “We’re going to make an album. What should we do?” You know, “We’ll do this, we’ll do a chorus, we’ll write some chords. Here’s a riff, what do you think?” Like that. Everybody put something into the pile, and after this huge pile of information an album would emerge.

JM: You’re probably sick of talking about it, but I have to ask about the Aqualung album, which was a huge success for the band. Looking back, what are your reflections on that album?

MB: Funnily enough, it was a hard album to make. We had a lot of problems in the studio, technical problems. We had a hard time getting good takes on the songs. We were struggling to get takes that sounded good, that were together. There was a lot of stress and anxiety in that record. But there were great songs, and sometimes out of all that heartache and stress something good comes out of it. Because it was so intense.

I can look beyond that album, where we just sort of sat in the studio and it all sort of flowed out, and we thought we were doing the best thing in the world. And the album was a flop. With Under Wraps we sort of locked ourselves away for two months, and thought we had the best album in the world, but people really didn’t like it [laughs]. There’s no prediction, and that’s the great thing about music. You just don’t know how people are going to receive it. Anything can happen from day to day, and I’m like this today. I’m writing music and recording it, and until I play what I’m going to play I don’t know what it’s going to be like.

JM: Some bands that have a hit album just record the same album over and over. But for Jethro Tull, the next one was totally a change in direction, Thick as a Brick. Were you on board with that change in direction?

MB: We never consciously thought we must do something different from album to album, but it just came naturally. I think we progressed as musicians. Our experiences on the road gave us the inspiration to go in different directions. We met other musicians, we played with bands we loved, we heard new music, and we took it in all the time. Essentially Jethro Tull worked 365 days a year. We never stopped working. We never took time out from playing music and listening to music and living music. So it was always evolving. As I say, there was no conscious decision to make one album different from another. It was just the way we were. There’s no way in the world that any of us, me or Ian, would look at the last album and think, “We need to write something a bit like that.” It’d be the last thing in the world, because I hate that concept that you’re reinventing music that you’ve already done. Once something is recorded and performed, you move on. Forget it. You’re over it. New year, new music, a new life. It’s always been that way.

JM: I’m probably in the minority, but I think that my favorite Jethro Tull album is Passion Play. What do you remember about the recording of that album?

MB: You know, Thick as a Brick was a huge success, and maybe we were a bit intimidated, like, “Oh my God, what are we going to do to move on from that?” We went to Paris. We went to this residential studio [Chateau d’Herouville] – in fact, it’s where Elton John did Honky Chateau – and we recorded a complete album that would’ve been Passion Play, but we had horrendous problems. The gear blew up. So much went wrong. We all got ill. We called it the Chateau d’Isaster because it was such a bad experience. We decided that we were going to go back to England, and we were not going to re-record what we had done. This sort of harks back to me saying that we always moved on. We never revisited where we’d been. So we scrapped the whole album, then went back to the studio in England and recorded what is now Passion Play. The original album did come out as Nightcap. It was a great album. The original Passion Play was really some great music and great ideas.

But the same Passion Play. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with it. Maybe it shouldn’t have had the same continuity from track to track, to make it like what people call a concept album, where there’s no breaks in between the songs. But like you say, there’s a lot of respect for it, but it had to live up to Thick as a Brick, and nothing could live up to that. It was asking too much of any piece of music to follow an album of that stature. It had to be a lesser beast in emotional terms. But in practical terms, in musical terms it wasn’t at all.

JM: I remember when Nightcap came out. Some of the themes did find their way into Passion Play, and some were totally new and different. There was one song on that called “Left Right” that I really liked, and I don’t think it ever got redone.

MB: No. Well, I think I’ve gotten everything that Jethro Tull ever recorded, but it’s a huge catalog, and sometimes I just sort of go through my CDs and vinyl and see a track and think, “I can’t remember that.” And I have to put it on and play it and go, “Oh my God.” It’s an immense catalog of music. Some things have been dormant for a few years, and I might find it, or Ian might find it and he plays it with his band. I’m the same. I’m always looking for things that are cool to do, and worth looking at.

JM: There are 40th anniversary remixes of the Jethro Tull albums that have been coming out. Have you checked those out at all?

MB: You know, I can only be honest, and I haven’t. Mainly it’s because [laughs] my life is busy. I play a lot of music, I write a lot of music, and we’re on the road a lot. Probably my least priority, not for any reason at all, is to listen to Jethro Tull, unless I’m thinking “I should listen to that in case I think we can play it live onstage.” So it’s usually for practical reasons, and I’m afraid I don’t sit and listen to albums. But I believe what I hear, and I’m happy that the remixes are good and have sort of brought things back to life again.

JM: One other album that really stands out to me in the catalog is Minstrel in the Gallery. What are your reflections on that album, and where the band was at then?

MB: Again, there’s a lot of that material that we play. We’re going to play the instrumental from Minstrel in the Gallery on the next tour, something we haven’t played for years and years. I did an instrumental version of “Requiem” on an acoustic guitar album called Away With Words. There’s just a lot of good songs, and it’s like every Tull album – there’s something in there that’s really good, on every album. It’s nice, and I wouldn’t say I’m in love with everything we ever did, but there’s enough in there that I can really be proud of what we’ve done. I’m very proud and happy that I’ve had 50 years of all that history.

JM: What advice would you give to an aspiring musician?

MB: To be modest, and never overestimate your own ability. And to be very broad-minded, and always listen to music you don’t like and analyze why you don’t like it, and how you would make it better rather than just listening to the things that you like. Because you become quite narrow-minded. I just think you’ve just got to listen, listen, listen, and learn. Listen and learn. Listen and learn. Practice, practice.

I mean, music is so infinite. There isn’t a day that I pick up the guitar and don’t get something from it. If I’m just sort of practicing scales, or put on a Robben Ford CD and jam along to it, something happens and I think, “Oh, OK, that’s a bit different.” The variables are just amazing. I think you have to be in awe and inspired by what music is. You’ve got to look everywhere for music. Look at classical music for the harmonies, the melody, the dynamics, the shear beauty of the construction. Listen to jazz for the technique, the blues for the emotion and the feel. Everything has something to offer, and you need to be very broad-minded to take all of that in.

JM: You mentioned that you were just at the studio recording. When can we look forward to another album coming out?

MB: [laughs] It’s going to be next year. It was going to be this year, but I can tell you right here and now that it’s going to be next year, because I’ve got two more weeks at home and then I’m flying to Oakland and we’re going to be playing for all the nice people on the West Coast. Time is precious, and there’s never enough time. I’m always behind schedule. I don’t want to rush it, and I’m not going to settle for second best. I’ll take the time. I’ve probably got six tracks, and I need the same again, and maybe some more. I not going to set myself a schedule. I’ll finish when I’m happy with it.

JM: But at least you’re far enough in that you’ve got to finish it, right?

MB: It was always the case with Tull that there was always a schedule, and the record company would pressure you. “It’s got to be out in the shops by this tour.” And, you know, nearly every time we killed ourselves to finish a record, working seven days a week for three months, and didn’t see the family. It really, really went crazy. And every time we ever did it, the record label would let you down. They wouldn’t have it out in time. The distribution wasn’t there… It was never us. It was always them. And you know what? I don’t sing to their tune anymore. It’s really when I’m ready.

JM: After the California tour, do you have any big plans?

MB: We’re over there for two months. We play the West Coast, then we play the East Coast. We finish at the end of October, and then we’re in the U.K. for about ten days in November. We’re in Italy for a week in December, then we’re back over in the States in February [laughs]. We’re in Europe April and May. It’s like the old days, and now I’m old. Yeah, it’s pretty full on.

Discussion

No comments for “Interview: Martin Barre”