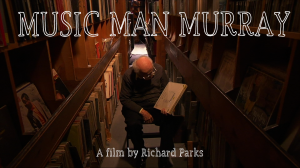

Murray Gershenz, aka Music Man Murray, is passionate about music, and has spent over 70 years collecting, buying, and selling records. But the time has come to sell his collection, which numbers in the hundreds of thousands. The catch – he wants his collection to stay intact. It sounds like he’d settle for half a million dollars, a bargain for a collection valued in the millions.

Murray’s story is captured in the documentary film Music Man Murray, which premieres at this year’s Santa Barbara International Film Festival. This film was produced and directed by Richard Parks, with music by his father Van Dyke Parks, who has had his hand in many notable music releases over the last five decades. Richard and Van Dyke responded to the following questions by email on January 20 and 21, 2012.

For an earlier interview with Van Dyke Parks, click here.

Jeff Moehlis: Could you give a quick overview of your film Music Man Murray?

Richard Parks: It’s a short documentary portrait of a lovable-slash-prickly elderly man named Murray Gershenz, now 89, as he struggles to sell the hundreds of thousands of records in his Los Angeles store. Murray’s records represent one of the largest collections of vinyl, anywhere. But the records are more of a setting for a biographical sketch of a man nearing the end of his life, taking stock of what he’ll leave behind. It also looks at Murray’s relationship with his son, Irv, who has worked in the store his whole life.

JM: Why did you choose this particular subject for your first documentary?

RP: If you want to hear a story, it’s always a good idea to talk to the oldest guy in the room. I had read that Murray was considering dumping the records in the trash if he couldn’t find a buyer soon, and decided somebody should take a camera inside his store before that happened. I grew up in L.A. and started collecting records as a teenager, and going to Murray’s was always like going to the temple — all hand-made shelves and esoteric cataloging and a gruff old man sequestered, listening to Jussi Bjorling. Of course the opportunities for picture and sound are so rich. It’s a real-life museum of Jurassic technology, and a piece of the L.A. I grew up in that will soon disappear forever.

JM: What is the status of Murray Gershenz’ attempt to sell his music collection?

RP: He’s still courting potential buyers, and as I understand entertaining all offers.

JM: What is the coolest record that you have found at his shop?

RP: There’s a sequence in the film of some hip-hop kids digging in the stacks. By chance, an old purple-sleeved compilation, “50 Guitars Go South of the Border,” appears in the frame on a long shot. That happens to be a record I bought from Murray’s probably 15 years ago. Only recently did I dig it out of my parents’ garage with some of my abandoned collection, and now here it is in my house with the white “Music Man Murray” sticker on the back. It’s not exactly the vinyl equivalent of a madeleine — and I’m still unclear why I bought this particular recording of Latin favorites — but there’s something there for me, personally, that this record made it into the film that was made about Murray’s life.

Van Dyke Parks: “La Bohéme” conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham, (wherein I sang in a group of street urchins). This vinyl LP excites memories of a life filled with titanic musical talent, that ran into a floe of rock and roll, with mixed blessings.

JM: I expect that this film will have an “end of an era” feeling to it. What do you think the future holds for record stores, and for music consumption in general?

RP: I avoid addressing this question in the film because I don’t have anything interesting to add to the conversation about what’s happened to the music industry. For my part, I’ll keep going to record stores and paying for music.

VDP: Rumours of the Death of the Music biz (with apologies to Mark Twain) — are greatly exaggerated!

It’s yet within our powers of invention to sell music locally that has a tactile component, sleeved with great art, and available as long as mom and pop hold up a shop on Main Street, Anywhere, USA.

JM: Do you mostly listen to vinyl, CDs, or MP3s, and why?

RP: There’s no real interesting reason, but I listen on all of those formats — and to internet radio quite a bit. I stream Jim Svejda from KUSC in L.A. (another L.A. institution) in my Oakland bungalow most nights while cooking dinner. His nasal mannerisms, and the whiff of browning onions, transport me back to the kitchen of my youth. After answering your last question, I put “50 Guitars Go South of the Border” on my turntable.

VDP: I don’t listen to anything beyond the car radio. Life’s too short.

JM: Could you describe the music that you composed for the film?

VDP: It’s a series of cues, skewed thematically (through the power of misquotation) from the song “Brother Can You Spare a Dime?” Subliminal reference of that sort, (i.e.: thematically driven) in underscore, can tighten the focal depth of field occupied by the main character.

Said song (“Brother Can You Spare a Dime?”) not only wraps that man in his own social origins in the Depression-era, and yet heightens the irony of his dilemma.

It wasn’t a creative idea of mine to use these thematic variations — it was already embedded in the documentary — a wise call on the director’s part.

The result? A study in the triumph of the human spirit, and a unique archive, with a value that exceeds its individual parts.

JM: What can we look forward to at your concert on January 31 at SOhO?

VDP: Getting out alive, with indelible pleasures held in the heart! This, through a harsh lite on piano/vocal, abetted by maestro David P. Jackson on upright bass. What a coup!

JM: Your album Arrangements Volume 1 came out recently. With such a vast body of work, how did you choose what to include on this?

VDP: Taking the advice of Lewis Carroll, I just began at the beginning! I felt it was time to wrest my early efforts from the ignominy of record company vaults, where they’ve been hidden. My work may not outlive me, yet its durability should be celebrated while I’m alive. It all reflects on the superior talents I’ve associated with for the past 45 years. I owe it to those that still live, and those who’ve stepped off the planet to feature their gifts.

JM: When can we look forward to Volume 2, and what will it contain?

VDP: Later this year. What it holds and the release date is basically a legal process. (I don’t bootleg. I am so legit!)

JM: Which of the Santa Barbara International Film Festival screenings will you be attending?

RP: I’m thrilled because this is my first all-access festival experience. I hope to see them all!

VDP: I’ll be led by the advice of my favorite documentary film director since Robert J. Flaherty, whose pioneering efforts introduced me to the potential of the genre — and ignited the passion I continued through adult life (with scores for the National Geographic Society). It’s an honor to have played a minor role in “Music Man Murray”, so richly relevant to my own wide-ranging musical obsessions.

JM: Do you have any other film projects in the works?

RP: Sure! I think this piece could set up a short series about technologies on the verge of obsolescence — I’d love to make a film about small community newspapers that never made it online, mixing visuals and text with an unfolding story. I was editor of two such papers and know there’s plenty of potential in that setting. Maybe there’s a trilogy in there, and the last one is set in a barbershop — though I suppose people are getting as many haircuts as ever. I’m also developing a couple of radio projects that should start coming out soon, and considering launching my acting career at 29, for the health insurance.

Music Man Murray

Discussion

No comments for “Interview: Richard and Van Dyke Parks”