Paul Kantner was a co-founder, singer, rhythm guitarist, and songwriter for the Sixties psychedelic band Jefferson Airplane, which is best known for the hits “Somebody To Love” and “White Rabbit”. His songwriting credits include “Crown of Creation”, “We Can Be Together”, “Volunteers” (co-written with bandmate Marty Balin) and “Wooden Ships” (co-written with David Crosby and Stephen Stills). Kantner stayed onboard when Jefferson Airplane morphed into Jefferson Starship.

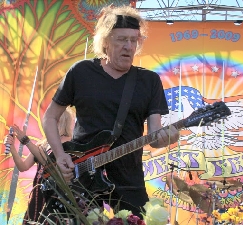

This interview was conducted by phone on 4/21/10. It formed the basis of a preview article for Jefferson Starship’s 4/30/10 show in Santa Barbara. Photo by L. Paul Mann

Jeff Moehlis: What should we expect from your upcoming concert in Santa Barbara?

Paul Kantner: We’re bringing back a couple songs, and doing a couple songs that we’ve never done before, and then our usual usual, and God only knows what will happen. I always look for an exciting time onstage, because it’s always so unexpectedly different every night.

We do have an extraordinary new woman singer named Cathy Richardson.

JM: She sang with you at the Heroes of Woodstock tour, right?

PK: Yes. We haven’t played for a little while, and I’m looking forward to getting back into the mode as it were.

JM: Will Marty Balin be joining you?

PK: Not in Santa Barbara, no. He gets out with us now and again, but lately he’s been less than more.

JM: How is touring now different from touring in the 1960’s and 1970’s?

PK: The music business has gone into quite a whirl. I hesitate to use the word “business” even, because record companies are going down, and record stores are going down, and the electronic stuff that’s out – I don’t mean the music but but the production of things – has all changed.

But going on the road and going onstage never changes in its own quiet kind of way. A certain thing occurs onstage that doesn’t occur anywhere else. The connection between live musicians and an audience is unrealizable in any other fashion, much like a theater play. It occurs in its own unique way almost every night, and one of the great things that I like about music, particularly live music but all music, is the way it connects to the brain and causes emotion to occur. Whatever the emotion may be. But that it can do that in the first place is almost like magic to me. Magic isn’t the right word, but it’s very metaphysical, if you will. Why that occurs after forty or whatever years, I still have yet to figure out. And I don’t know that I really want to. I just know that I can wield the music, and play it, and enjoy it, and watch other people enjoy it, and then see repercussions over time that come from both the music and the ideas specified in the music. That’s very satisfying on many levels.

I always remind myself that when musicians go to work, they play. I intend to keep it that way as long as I can.

JM: You’re probably planning to play some Jefferson Airplane songs at the show?

PK: We play everything. We play some stuff sometimes from before Jefferson Airplane, even.

JM: Such as?

PK: The song of a guy named Fred Neil. We do a song of his that I did long before Jefferson Airplane was even a thought called “Other Side of This Life”. Occasionally we’ll do another song called “High Flying Bird” which is an old modern folk song.

We do from that all the way to Jefferson Airplane and Jefferson Starship and my solo albums and Blows Against The Empire, to our latest album which has a whole lot of, oddly enough, folk songs on it again: the Weavers, to sailing songs, to a Bob Dylan song we do that I’m really quite fond of. So we do a whole of different stuff. It changes every night, and I usually don’t make the set up until a half hour before the show. We have about a hundred songs that we can draw from, so we’re pretty well flush with songs.

JM: You have quite a songbook to draw from.

PK: And half of them aren’t even on the list yet. We’re bringing a couple this next tour, one called “Lightning Rose” and maybe another one called “Go To Her” over the period of the spring and summer.

JM: Can I ask for your reflections on a few songs that you wrote or co-wrote?

PK: Sure.

JM: First, how about “Wild Tyme” from After Bathing at Baxter’s?

PK: That was our most extreme, out-there album, I think.

JM: It seems that song captured the time, the craziness and all.

PK: It’s a sweet, gentle song, though. It is unusual, both for the subject matter and the structure of the song. I usually don’t write songs like that. The body of it was just me reflecting on the times around us in a quiet kind of way. Just to be unusual.

JM: Also on that album is “The Ballad of You & Me & Pooneil”.

PK: That’s just a kick-ass rock and roll song that draws on Winnie the Pooh and Fred Neil and others that contributed ideas to the thing. Basically it’s just a good rock and roll song. We still play that lots, and it kicks.

JM: Then there’s “The House at Pooneil Corners”.

PK: “Pooneil Corners” is a follow-up to “You & Me & Pooneil”.

JM: It has a much darker vibe. Had things gone sour by that point?

PK: No, no. I gave that to Marty to write [laughs], and he made it a sour, end-of-the-world kind of song. The chord changes sort of speculate on that kind of idea, as well.

One of the particular things I like about “Pooneil Corners” is Jack Casady’s bass part. It almost drives the whole song. We tried to do it last year. Sometimes we play without a bass player, and our keyboard player takes over the bottom end. But there’s nothing that drives that song like a live, regular bass, and so we sometimes tried it, and at the moment it’s in the B-list. But it’s one we know.

JM: Another one that has a darker vibe is “Crown of Creation”.

PK: Well, it has a darker vibe. But at the end, where it goes “Life is change / How it differs from the rocks” is pretty positive, I think. It speaks of things that are difficult, and then hopefully gives you a direction to go to overcome that difficulty, or live with it and deal with it properly.

JM: On the next album, there are are a couple of, for the lack of a better term, classic hippie songs. What’s your reflection on “We Can Be Together”?

PK: “We Can Be Together” – yeah, that was sort of my countercultural song, where it celebrated a lot of the stuff that was going on at the time. Which was basically the “fuck authority” kind of feeling that came out of The Sixties. Some of the lyrics actually came from graffiti. And then it resolves itself into what I think is one of my more beautiful choruses, with harmony and hopeful forward motion. In the midst of all that chaos we can be together. For what it’s worth, sometimes we even are together [laughs] on several different issues.

JM: Then there’s another song on that album, “Volunteers”.

PK: It’s sort of a short version. Marty wrote most of the lyrics, and I wrote most of the music. We just came up with that almost as an afterthought, when we were making the album. We just took the lick from “We Can Be Together” and extended it for like three or four minutes, and then riffed on it. I thought Marty sings a great lead vocal on it, and it sort of specifies the whole situation, that you’ve got to do something about this. You can’t just sit around and complain about it.

You know, that was the big difference between Berkeley and San Francisco in The Sixties. Berkeley was still on this soapbox kind of way of doing things. Get up and whine and bitch about this, that, and the other thing, and try to get people to do something.

We had the unusual fortune in San Francisco, almost accidentally, of being able to focus on good things in life. And rather than complain about bad things, to a great degree we spent a lot of time musically and lyrically pointing out things that could make your life better, that had made our lives better. And we focused on doing those a lot more than normal, as opposed to just complaining about things that are. We find that a lot of things that are bad tend to go away when people are concentrating on things that they are doing that are good. And they just dissolve of their own lack of attention. That’s sort of what that’s about.

JM: Same album, the song “Wooden Ships”, written with David Crosby and Stephen Stills. How did that come about?

PK: David had this beautiful series of chord changes for about two years, and he couldn’t write anything to them. I know that David is a big fan of sailing boats on the ocean, and I went with Grace [Slick] and visited his boat one time, and just decided to write that song for David. He liked it, and we went from there. David added a few lines here and there, Stephen Stills added one verse, and I did most of the rest of the lyrics. David did most of the music. I did the beginning part a little, but most of the music was written by David, lyric-less.

JM: There was a music critic back in The Sixties, Ralph Gleason…

PK: Gleason, yeah, he was very helpful to us.

JM: He wrote a book about Jefferson Airplane, and he asked what albums you guys listen to, and one of the band members – I don’t remember which one – said, “We don’t need to listen to albums. Crosby, Stills, and Nash are hanging out at our place, and we just listen to them all the time.” Is that really what was happening back then.?

PK: Yeah. It was a very rich time. There was a guy from L.A. called Wally Heider who opened a studio in San Francisco called Wally Heider Studios. He was a really good studio builder from Los Angeles, and there were like three or four different studios in it from large to small. At this, that, or another time there was always Crosby, Stills, and Nash, and Jerry Garcia, The Dead, Santana. All these people were going in and out of this studio.

They sort of built it around us, actually. When they finally got a studio together we went in there, and they were still building the studio while we were recording Volunteers, which I think was the first album we recorded there. All these people were there.

You know, making records, or CDs now, is somewhat akin to movie making, in that you spend a whole lot of time waiting for them to set this, that, or the other thing up properly. So while they were doing that we would just wander around to the other studios to see who was doing what where.

I had the great fortune later, when I was doing an album called Blows Against The Empire, a science fiction album, to have all of those people around and available. They would just come in, and “Oh, I could play something on there” they’d say, and I’d say, “Well, go right ahead” [laughs]. And I got some of Garcia’s best pedal steel work. He was just starting to learn the pedal steel, so he was a little out there in terms of what he did, and I said, “Just go as far as you want.” We recorded almost everything that he did, and chose amongst it all, what to put on the album. And Crosby and Nash, particularly, came in and did some really beautiful harmonies, and David wrote a song with me called “Have You Seen The Stars Tonite”. It was just a very nutritious time musically in San Francisco for that to occur. I got to, accidentally, take full advantage of it.

JM: I was born in 1970, so I missed all the fun…

PK: That’s what my children say. They say, “Oh Dad, you got to do everything. I don’t get to do anything.” And I say, you can find something to do. But then I joke that the sex, drugs, and rock and roll has turned into AIDS, beer, and Barry Manilow. [laughs]

JM: That’s depressing.

PK: To a certain extent, through the disco era and into The Eighties, music did sort of filter to a non-communicate-able level for me. I just got stuck listening to the old folk singers that I’m particularly fond of. Specifically the Weavers and Pete Seeger. As I say, we used a couple Weavers songs on the last folk album that we made, Jefferson’s Tree of Liberty that came out last year. We used several Weavers songs, and a Bob Dylan song, and then some older folk songs, a slave song that might have been appropriate… we’re working on an album right now of Civil War songs. There’s a song called “Follow the Drinking Gourd” which was a slave song that fit on [Jefferson’s Tree of Liberty] but would’ve also fit on our Civil War album.

There’s a huge amount of great music, a lot of it Irish, which is my favorite music in the world really, Irish and Scottish music. For some reason those chord changes get me the same way that blues songs get people who love blues. I do that for Irish music. It just clicks with me instantaneously. That’s where a lot of my vocal harmonies, and ways of doing harmony come from. From that and the Weavers who used a lot of that same kind of music.

JM: Speaking of harmonies, back when Jefferson Airplane was recording in the studio, did you work out the harmonies beforehand?

PK: At the very beginning, with our first singer, I would write out some harmonies. But then when Grace got in the band, the combination of not knowing what you’re really going to do between Grace and Marty and myself, produced some of the most extravagantly lovely, in my opinion, harmonies. Most of them accidental, and very few bad notes.

I was the one who was responsible mostly for the harmony songs in the Airplane and the Starship. Marty did his solo business, and Grace did her solo business, and it was left to me to fashion these harmony songs, coming from the Weavers and God knows where else. We just did it, accidentally. I’d have a song, I’d go out and sing it once, and then they would start singing along, and they’d find places where to go, and where their range was good. They just came together, almost as an accident really. A fortuitous accident, but accidentally nonetheless.

JM: What about the instrumental arrangements? I asked you about the song “Wild Tyme”, which has a really cool psychedelic lead guitar line. Was that worked out beforehand?

PK: Same thing. In terms of my songs, I would write a song and play the chords on the guitar, and sing a background vocal or a vocal, and then we’d just go out in the studio. I’d give them chord changes on paper, and we’d just go out and start playing. Whatever came out – same way with the vocals – came out. Jorma [Kaukonen] was that kind of a guitar player, where he would just play. Even live onstage it would be different every night in its own way. Same with Jack on bass.

Like Grace and Marty and me singing together, the things just came together without a great deal of what you call planning or arranging. The only arrangement we had was the chord changes, and then we’d play whatever we liked in the middle of them. We’re not the kind of band, never have been, like The Eagles who go out and play their exact album exactly. And I can see the value in that from their point of view, but for us it would get very boring after less than a week on the road. It would just be too repetitively boring for me. And you would miss all of the surprises that come when you’ve got instrumentalists and vocalists working a capella or straight ahead without any serious arrangement to have to follow. That works very well for me, and us, and always has.

JM: You’ve brought up the names of the musicians in the classic line-up of Jefferson Airplane. They’re all very talented musicians, they they wrote songs, and so on. Was it difficult for people to get their ideas heard in the band?

PK: Not at all. The principal songwriters in those days were me and Marty and Grace. Then we encouraged Jorma to write a song or two out of his lexicon. He started writing songs, so we’d add those to the mix. That was about the extent of it in Airplane.

In Starship it was still Grace and me at that point. David Freiberg, who had joined us, wrote a couple songs. Pete Sears wrote a couple songs. But it was mainly me and Grace who wrote most of the songs.

The last album, like I said, was folk songs, and the next album is Civil War folk songs. I’ll probably manage to jam at least one crazy song of mine in there as well.

JM: Speaking of “crazy songs”, one which I’d like to get your reflection on is “Stairway to Cleveland”.

PK: I was going with a girl who had come from Cleveland, and I wanted to do a just a good trashy – not quite punk – but thrashing rock and roll song. And it just came out on its own really, without much plotting or planning. Just putting lyrics together with that strange beat that is in there, that is unusual for us. It was just a creation of its own expression about rock and roll and all the things that were going on with us at the time.

JM: I love that on the lyric sheet it says “Your manager is a wonderful person” but you sing “Your manager’s an asshole”.

PK: We were just skirting around an issue, I think. I think RCA gave some complaint about using “asshole” on the lyric sheet, even though it was on the record. That might be the reason I changed it, just to be amusing.

JM: In Jefferson Airplane you were at a lot of the key events of The Sixties. What are your memories of the Human Be-In?

PK: Well, we went into the park expecting two or three hundred people to show up, like we normally did. And it turned out to be twenty thousand, or something like that. Just that alone was exhilarating, to know that there were that many crazy people in the nearby area of San Francisco, where we thought we weren’t very many. All of the sudden there’s all these people who have this inclination to go in that direction. It was a great surprise. It was quite joyous to be there. It was a great joy to be there amongst the crowd.

The show, as always in San Francisco, at the Fillmore and everywhere else, was really secondary to the gathering itself. Almost like a harvest festival. It was good luck if the night you went to the Fillmore for this festival there was somebody good playing as well, but it wasn’t the draw. It wasn’t the prime draw. The prime draw was just all of these people recognizing that they’re here and enjoying each other, and doing what you do. The music, like I say, was secondary. As Grace once said, it was a good place to be at the party, because you could be up on the stage and see the whole party in front of you, and see what was going on where, and that sort of thing.

JM: Another big event, obviously, was Woodstock. What is your take on the original Woodstock?

PK: It was pretty much fun. It was rainy and muddy, and had all sorts of problems. Again, the gathering was extraordinary, and everything that went on over and above the stage was extraordinary. Despite the rain and the mud and the this and the that, I personally had quite a good time.

JM: Then the dark side came. What went wrong with Altamont?

PK: I think that the normal Hell’s Angels, who even we used – not quite for security but watching out for this, that, and the other thing at shows in the park and other things – didn’t come that day because they were having a meeting. Much of what we had was a bunch of glue-sniffing wannabes, and new Angels who were trying to prove themselves. Then people started mildly bumping into their motorcycles, and they got all out of hand, and had been using too many variations of this, that, or the other drug. And it just descended into what I refer to as “one life that I could have lost.” How many I have, I don’t know, but that was a dangerous thing.

JM: Is it correct that Marty got hit while he was onstage?

PK: He did. Because told them to fuck off, or something like that. The guy who hit him came back to apologize, when he found out who it was, and said “Sorry I hit you.” And Marty was sort of half waking up, and looked up and said, “Fuck you”. The guy hit him again. “You don’t say ‘fuck you’ to a Hell’s Angel. Don’t you know that?”

I went up and gave some shit to the guy later. There’s this picture of me with this big, huge, eight foot tall guy with an animal hat on his head, and I’m looking up at him with my head back and my glasses on, reading him out like some teacher reading out a high school guy that fucked up. He’s going, “I’m sorry, man” but he could have just as easily popped me. I didn’t say “fuck you”, knowing what not to do. I just gave him the principal attitude, and he apologized for it. And I said, “don’t let it happen again.” Then he invited me back for a party at the Hell’s Angels house after the show, and I said I had to go back to San Francisco.

JM: So was it one of the Hell’s Angels that hit Marty?

PK: I’m pretty sure it was one of the Hell’s Angels. It may have even been the guy I was reading out.

JM: What advice would you give to an aspiring musician?

PK: Just keep playing. Play your guitar as many places as you can. If you want to work with other musicians, go to places where other musicians are. And learn from them.

Hopefully you’ll have some favorite musicians and music. The way I started out was copying and learning things from people that I liked, like Fred Neil and the Weavers, and stuff like that. Eventually I started writing a song or two. The first song I ever wrote actually became part of the lyrics of “Wooden Ships”. Part of the lyrics of the first song I ever wrote.

Go places that music exists, and immerse yourself in it in as many ways you can find enjoyable and possible. And be around people who play music, and give you new ideas that you wouldn’t have thought of. Just sitting in your back room making up music and putting it on a tape recorder is fine for a certain element of things. But for me I love the interaction between musicians, which for me produces usually a “one and one equals three” kind of situation. And things occur that you never would have thought of by yourself, and other people’s influences touch you and move you. So, yeah, other people.

JM: You had mentioned science fiction before. How would you say that science fiction has influenced your songwriting?

PK: I’ve been reading science fiction since I was a child. I read all of the basic guys, Asimov and Heinlein, etc, etc. One of the first books that got me into reading was science fiction. So I’ve always treasured it, and for some reason I’ve been drawn to it. The concepts involved allow almost anything to occur within the story. And just the idea of exploring the world. Much like I was talking about before between us and Berkeley, where they complained about this, that, and the other thing, and we explored new areas of things to do. God knows why, but we got away with it. We all probably should have been thrown in jail for twenty years. But we got away with exploring. So science fiction is just another mode of exploring for me, and I love to explore the unknown.

JM: Is it true that you were the one who coined the phrase, “If you remember The Sixties, then you weren’t actually there”?

PK: Everybody has credit for that. I think Robin Williams was the first one that I know of who said it.

JM: But maybe you said it and don’t remember, right?

Thank you so much for this interview. I am particularly interested in Fred Neil, and have been researching him for a couple of years. This is the first I’ve learned of his influence on Paul.

Thank you

a very good interview indeed

a lot of good questions

i love the work you did here

Great interview! I could listen to you guys chat for hours. Insightful and relaxed!