When I interviewed punk rock bass guitar hero Mike Watt a couple years ago, he referred to guitarist Nels Cline’s musicianship by saying, “He has no fear”. And when you consider Cline’s diverse discography, that seems like an apt description.

Cline is best known for being the lead guitarist for Wilco, a position he has held for the past ten years. He has also performed and/or recorded with a variety of other artists including Watt, Thurston Moore, Charlie Haden, and his wife Yuka Honda, in styles including jazz, free improvisation, and avant rock.

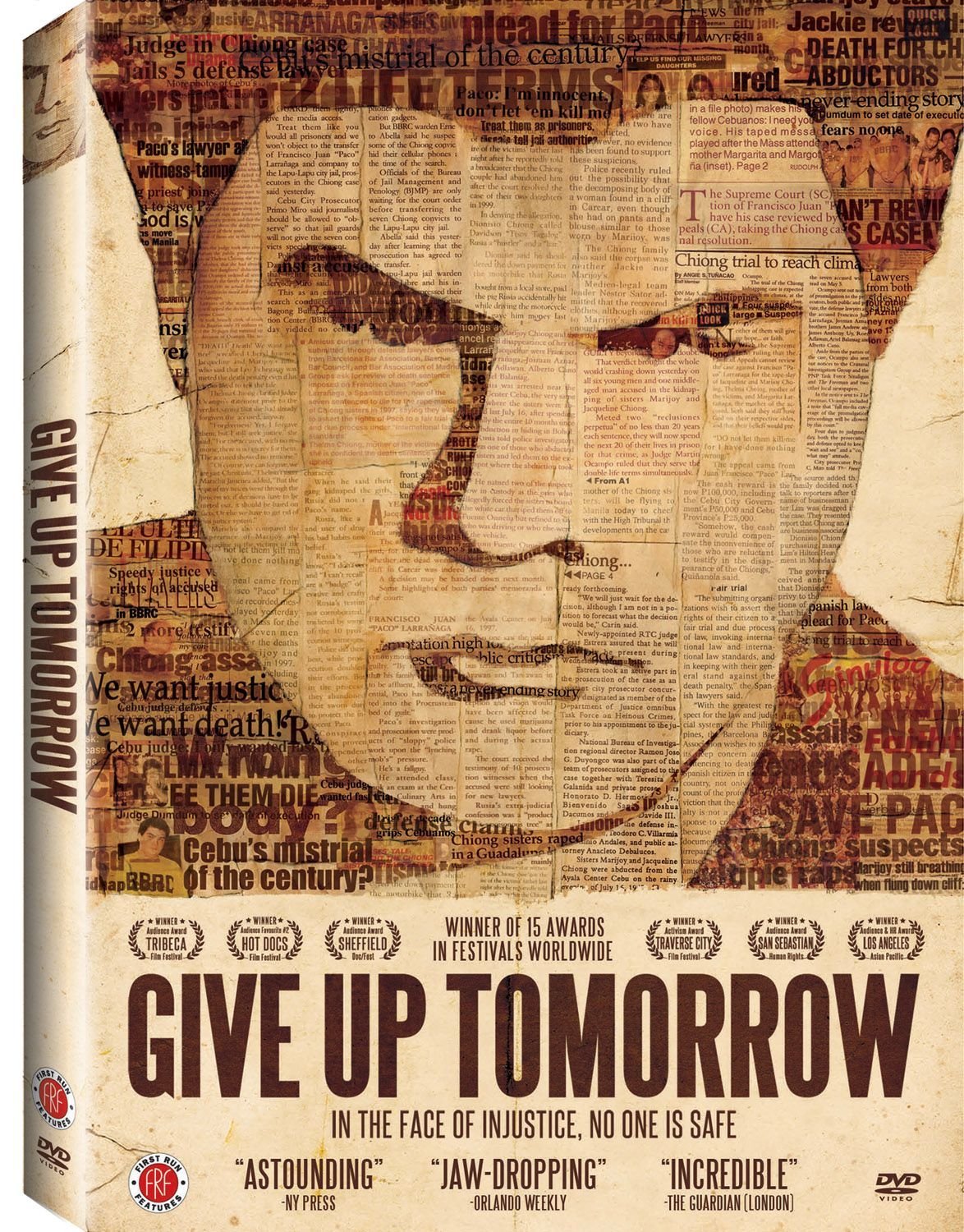

In a new project, Cline and Honda will be composing the soundtrack for an upcoming documentary called Almost Sunrise, which follows the healing journey of two veterans who don’t want to become part of the shocking statistic that 22 former American soldiers commit suicide every day. Almost Sunrise is directed by Michael Collins, who also directed the award-winning film Give Up Tomorrow, and recently received $100K in support from a Kickstarter campaign to help finance the editing of hundreds of hours of footage.

Cline graciously took part of a rare day off to talk about the Almost Sunrise project, plus his former job at Rhino Records and making music with Wilco and Mike Watt. The interview was done by phone on 6/10/14.

Jeff Moehlis: How did you get involved with the documentary Almost Sunrise?

Nels Cline: I met Michael Collins through my wife Yuka a few years ago. He’s one of her good friends, and did the film Give Up Tomorrow. He’s a fantastic person.

JM: Do you have any personal connection, that you’re willing to share of course, to the topics that the documentary covers, such as veteran’s issues, mental health, and so on?

NC: Not really. To me, it was just the absolute surprise and shock at the statistics that Yuka forwarded to me by email. I would have done the film anyway, frankly, whatever Michael was doing the film on. If he was doing it on, you know, a certain kind of baboon or something, it would’ve been fine, because Michael’s awesome.

But I had no inkling that so many veterans were committing suicide, at such an alarming rate. I don’t have any intimate family history with anything like that. My parents were much older than all of my friends’ parents. My dad was stationed in World War II somewhere in the south. He was actually too old to be drafted but they drafted him anyway. And it was all fine with him. I know others who served. In my day it was all about Vietnam – I’m 58 years old and registered for the draft. But no, I don’t know any returning veterans.

JM: It’s kind of hard to keep track of all of the projects that you’ve been involved with. Have you ever done anything like this before?

NC: Yeah, I have. It’s been a while since I’ve composed specifically for a soundtrack, and I’m looking forward to doing it with Yuka. I scored two really horrible movies in the 90’s. Those were done pretty much beyond low budget. And I played on a few soundtracks.

I guess the last one I played on was a documentary about the man who coined the term “genocide” and made it a crime against humanity, Raphael Lemkin. My good friend Dougie Bowne is now finishing that soundtrack. But I’ve done a little bit of it, a particular scene that was causing the editors some grief, so Sean Lennon and Erik Friedlander and Shahzad Ismaily and I did some playing on that. That’s the last soundtrack effort. But now Dougie is scoring, I think, that entire film, and just keeping a few of the things that we already did [laughs]. We were just sort of a repair crew at that point.

JM: Do you know the rough timeline for the Almost Sunshine project? It sounds like you haven’t recorded yet.

NC: No, we haven’t. I actually don’t, and I’m certainly concerned in that both Yuka’s and my schedules are pretty much solid until early next year. But we’re going to just figure it out, because we can work here in the house. I tend to work really quickly, and when Yuka starts gettin in her sound design mode she can be rather meticulous, so we’ll just have to figure out the pacing.

JM: Speaking of documentaries, a few years ago I saw the documentary Rhino Resurrected, and it had a few clips of you. I was curious if you could reminisce a little bit about working at Rhino Records?

NC: [laughs] Well, I wasn’t super enthused with that movie. I guess I didn’t really know it was a movie just about Richard Foos when I was being interviewed for that, so it didn’t really tell the story of Rhino that I knew, which extended beyond Richard Foos owning the store. There were many years with different staff and different kinds of memories that weren’t really applicable to the Foos years.

I worked there for almost ten years, and it was an absolutely remarkable experience. And yes, of course, it was rather dysfunctional and neurotic in some ways, and snarky and all those things that we associate with the snobbery of independent record stores, now immortalized in the movie High Fidelity and the book, which I haven’t read. It was a locus of activity. It was a meeting place. It was like a community center in some ways, which I would attribute to a combination of just the record store phenomenon itself, but also particular to the smallness of Rhino Records in its early days. I think PooBah was similar, as well, in Pasadena, smaller than the store that we were modeled on which was Aron’s Records in West Hollywood.

So all kinds of things went on there that were musical and non-musical. It was a time when people were very obsessed with their music in a specific way, and things were smaller so it was manageable. You could actually potentially hear everything if you wanted to that came through the store.

And I met a lot of my musician colleagues while they were shopping there. People like Charlie Haden and Vinny Golia, and the list goes on. There were many people I didn’t end up playing with that I at least got to sell records to [laughs], like Ry Cooder and David Hidalgo and Dave Alvin and Lux and Ivy from The Cramps. All kinds of colorful individuals.

And I think that the fact that people could go to any record store of worth, and have this kind of random experience of searching through the stacks for whatever rather that having to have a specifically directed mode of shopping in mind for a title… it was kind of a fun activity. And, yeah, it ended up being rather social as well.

JM: We miss those stores nowadays.

NC: I don’t really like to be in this role of nostalgia-meister, specifically, but I think it’s worth reminiscing about, maybe, what the value of that experience was, only in the sense that it could create connections between people, not just connections to culture. Not just music, it can be anything. To know that you’re going to be around some like-minded individuals, around people who are very challenging. It wasn’t just musicians that were hanging out at Rhino. It was music writers, people from the music industry would come in.

I was just watching a movie the other night, and it said something like Music Guru – there was a woman named Kathy Nelson who was a record industry person. I don’t remember if she was in A&R at that time. But it just jogged my memory. I remember several people from the so-called music industry who were extremely cool, and Kathy was one of them. Some of these people have survived and become music supervisors or DJs or whatever it is they’re doing. But everybody hung out and talked and compared notes.

And the other thing was that I became exposed to a lot of music that I would not have been exposed to otherwise. In the late 70’s, when I started working at the record store, it was the height of the punk era. And I was on Jazz Island, you know. I was the first guy at the store to be a quiet individual, generally [laughs], rather than obnoxious or whatever. Not everybody was loud, but there were some distinct personalities that didn’t mind saying what they were thinking.

But beyond that, I was trying to assess and absorb John Coltrane and Weather Report, and listening to Derek Bailey, and as such had no real interest in a lot of other stuff that was going on. At least so I thought. But gradually I ended up hearing pretty much every independent single that came through the store, because we just took everything on consignment or we just bought it outright. So every underground record was there, pretty much. If someone brought it to the store we had it.

I remember much later when I was interested in this music and following it by the early 80’s, people like Calvin [Johnson] from K Records coming in and selling me stuff personally. Shonen Knife and whatever. It was really nice, actually, to hear not just all that music and get interested in it, but also just how I became aware of Nick Drake, for example, when one of the employees was really into Nick Drake and really into the folk scene in the late 70’s. And how I heard a lot of other blues and rockabilly, and this kind of stuff that I probably would not have been as aware of. So it was a real gift, in that way.

Sometimes, of course, it’s overkill. It’s hard to hear music for eight hours at a stretch, especially when you want to go home and practice and learn some things. But ultimately it was more enriching than aggravating.

JM: I’m sorry, but I have to ask you about Wilco. How does your approach to playing guitar differ with Wilco than other projects?

NC: Well, in some ways it’s very similar, because I’m thinking about the sound of the guitar, and thinking about my specific kind of syntax, the use of various effects or looping, and whether it’s going to be applicable to whatever my ear brings to bear on the situation in terms of note choice. But, you know, Wilco’s not specifically an improvisational endeavor, so it differs in that sense primarily. We play a setlist, and it’s what in so-called rock and roll they call “a show” rather than in improvised music or jazz where they call it “a set”. So there is a show aspect to it because you have fancy lights and a big audience and a setlist that is very slaved over by Mr. Tweedy to make sure that the audience is getting all their food groups. And it’s a balanced presentation, it’s got all the highs and lows, the louds and softs.

I do my own sets that way in my own band, The Nels Cline Singers, within the parameters of that music, trying to present a well-rounded program with all the possibilities potentially explored and every stone uncovered. In my own music or in improvised music I rarely have to have memorized as many songs as I know in Wilco [laughs]. But that was a gradual process. It started out with about 65 and just sort of expanded from there. It wasn’t like I had to learn 200 songs all at once.

JM: Is there any news to report on the next Wilco album?

NC: It’s gonna be a while. We’re taking a break. There were some experimental recordings done a while back, and Jeff [Tweedy] has got another thing that he’s doing right now, and we’re all doing other stuff. So I don’t know the ETA. I know we’re going to hunker down and get to work pretty soon. We’ve got some residencies coming up later this year to celebrate Wilco’s 20th year as a rock band in the world. So we’re going to play in some towns for a few nights, try to play a bunch of songs.

JM: I’m a big fan of Mike Watt. How did you end up playing with him?

NC: I met Watt officially when both Thurston Moore and David Crouch, the manager of Rhino, endeavored to bring us together for potential music making. But I had met the Minutemen en masse at at gig at McCabe’s in the early 80’s.

At some point or other he asked me to play on the last fIREHOSE record that Mascis was producing, Mr. Machinery Operator. I played about a thirty second guitar solo on that, and we sort of bartered that if I did that, he’d play on the B-side of a 7-inch single by my old trio Nels Cline Trio, because we were in-between bass players. And he did that, and we recorded that in my friend Wayne Peet’s garage in West L.A. The rest is history [laughs].

I ended up playing a lot on Ball-Hog or Tugboat? along with the drummer from my trio, Michael Preussner. Watt called us “The Break-in Crew” because we were the first tracks for that record, and did a fair amount of material. There’s still a lot of stuff from that record that hasn’t been released, a few songs at least. Anyway, that’s how it all started. Eventually I ended up going on the road with him, and with Michael and Vince Meghrouni as The Crew of the Flying Saucer. And I’m actually going to do a recording project with Watt next month here in New York, primarily of his basslines and outlines, and it’s going to be called Big Walnuts Yonder, with me and Greg Saunier, the drummer from Deerhoof, and Nick Reinhart, a friend of Watt’s from Pedro. We’re going to flesh out a whole record in about three days, and it’ll be about the fourth record that I’ve done with Watt that hasn’t emerged into the world.

He’s got a bunch of stuff in the can, not just stuff with me but lots of other stuff. There are two Brother’s Sister’s Daughter records, which is this mostly-Japanese project, they haven’t released. And a Black Gang reunion record with me and Bob Lee. The initial recording was completed, God [laughs], it’s been a long time now. I’m not sure how long ago. But, anyway, he’s piling up the stuff in the can. It’s exploding out of the can, probably, at this point.

JM: What advice would you give to an aspiring musician?

NC: Sorry to sound trite, but in my case I think that there’s a confluence, if you will, of persistence or perseverance, and deep denial [laughs]. If you can manage to not give up what you love doing, if you really love doing it, then I think that’s my main advice.

The other advice I have is, if you want to do something that’s not normal with music, it’s going to be a tough road, but do it and don’t take any shit. Because you might change the way we think about music forever. But it’s a very tough road. In spite of the fact that you have to learn a lot of stuff, it’s easier to play other people’s music, and sort of fit in. That certainly has its own skill set, which is a language that one must learn. But to walk on the road less hoed, or one unhoed, is certainly a much more difficult endeavor just in terms of staying on that road, because people will want to deter you, they’ll want to tell you that you don’t know what you’re doing, or they’ll want to tell you that you can’t do that, or whatever it is. And I say, do it, and don’t take any shit if you really are committed to that idea.

But the perseverance thing is the number one thing, because, God, there were times when I just thought that I was delusional, that I should not be pursuing music anymore. Because it was basically kind of ruining my life [laughs]. Struggling and driving myself insane in the head, you know? But I didn’t give up, and things got really, really lovely, eventually. It did take a long time, but then again, number one, I’m not that fucking talented and I just kind of gradually got better, I think. The other thing is I can’t do anything else [laughs]. But if I had not thought, “Ah, yeah, this year’s so much better than last year,” like every year’s a little better than the last one, I would’ve certainly seen my life as a big long delusional kind of sad story and given up. But I was convinced that every year was better, and because I enjoy what I do so much, it wasn’t that hard to keep going.

But I think it is hard for some people, especially if they start really thinking about it, and they realize that the rewards are few other than the doing. At least for a very long time. I mean, I was never out there to make money or be a star, or anything like that. I wanted to survive playing music so I could keep playing. But it’s much easier said than done.

JM: Where are you speaking to me from?

NC: New York City. I live here in the West Village, and I actually have the day to myself today to take care of some things. Then I’m playing the next couple of days here in New York, and then touring in another couple of weeks. I’m going out with a young man named Julian Lage. We have a guitar duo and are playing a couple of jazz festivals.

Discussion

No comments for “Interview: Nels Cline”