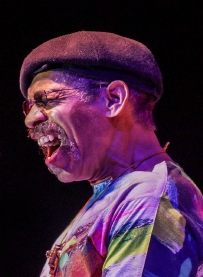

Keyboard player/singer Lonnie Jordan is one of the founding members of the band WAR, a melting pot of soul, funk, Latin, and jazz influences whose songs include “Low Rider”, “Spill the Wine”, “Why Can’t We Be Friends?”, and “The Cisco Kid”.

WAR’s fortunes took off when singer Eric Burdon asked them to back him up after leaving the Animals. They recorded two albums together, and had a huge hit song in 1970 with “Spill the Wine”.

WAR raged on after Burdon’s departure, and in 1972 they released the Number One album The World Is a Ghetto. More ’70’s success followed, with “Low Rider”, especially, striking a chord which resonates to this day.

This interview was for a preview article for noozhawk.com for the 5/27/18 WAR concert at the Santa Barbara Bowl, a show with George Clinton & Parliament Funkadelic also on the bill. It was done by phone on 5/7/18.

Jeff Moehlis: This is a show where WAR is sharing the bill with George Clinton. Did you and George know each other back in the ’70’s?

Lonnie Jordan: Yeah, we knew each other. We didn’t actually hang out, but we always met each other onstage whenever we would play together back in the day. It was fun. It was just like one big party [laughs].

JM: Were you surprised to hear that he’s planning to retire from touring?

LJ: Not really. You know, he had his run. Like the song “Home” says: “I’ve had my run and I’m ready to go home.” So no, I’m not surprised.

And he’s deserving to retire. But to be honest with you, I doubt if he does retire. It’s hard to retire when you’re making music, and when you’re making people happy. I’m just sayin’ [laughs]. I don’t plan to retire. James Brown didn’t retire.

JM: I imagine that even if he stops touring, he’ll keep writing and recording music.

LJ: Oh yeah, for sure. I mean look at Tony Bennett, my favorite artist. Frank Sinatra couldn’t retire either. Nobody retires. They may get a little tired, but they don’t retire.

JM: Going way back to WAR’s early years, how did the song “Spill the Wine” come together?

LJ: You’ve probably heard a million stories, but the story I’m giving you is from the horse’s mouth. We were in the studio still creating “Spill the Wine”. We were done with the track, and that’s another story that has to do with a connection that I had a run-in with Jim Morrison. That’s a whole other story [laughs]. But to make the story shorter and everything…

We were in the studio at Wally Heider’s in Los Angeles, and it just so happened that Eric [Burdon] was in the song booth improvising. He was trying to come up with a story. We were all having a hard time, and a young lady was in the booth with him. I won’t mention any names, and I won’t even tell you what they were doing.

I had bought a bottle on wine – back in those days I wasn’t really that into wines. I just figured wine is wine. So I bought a big bottle of Boone’s Farm [laughs]. You know, that’s all I knew. Otherwise it would’ve been whiskey. So I had this big bottle sitting on the left side of the console board, and a styrofoam cup. But as I was watching Eric in a dark lit room while the track was playing, he couldn’t seem to come up with anything. But I noticed he was being inspired in there – I won’t go any further than that. As he was being inspired, I took the top off and poured this big bottle of wine still looking at Eric. I’m like, “Wow, I should be in there.” [laughs] As I was pouring it I wasn’t paying any attention, and it all spilled over into the board, and the board started smoking [laughs].

It didn’t ruin the tape. The tape was still going, the volume was still there, but everyone thought it was funny and Jerry [Goldstein] had to get on the horn to tell Eric in the monitors in his earphones that Lonnie spilled wine in the board. And that was a “bingo” from that point on. “Spill the wine.” Eric was just having fun. He just started singing and blurting out things, and that was one of the blurts he blurted out: “Spill the wine”.

And next thing you know, Jerry and Chris Upton, the engineer, had this bulb lit up in their head and it just went from there. And the girl that was in the room, she was already speaking Spanish on the track. Nothing connected or related to “Spill the wine”. She already layered hers on the track of what they were doing, which, again, that’s personal [laughs]. So that was there, the track was there, we just needed to put a story to the struck. So up came “Spill the wine”, and there it was.

JM: You mentioned Jim Morrison. From the horse’s mouth, did you really punch Jim Morrison at that party?

LJ: No, I still don’t believe it. Jerry Goldstein said I did, Eric said I did. I did not punch Jim. I can tell you what I did. I think they all turned around and saw him backing up slowly into the fireplace. They were all high. I wasn’t taking any acid, so I can tell you I knew what I was doing. I wasn’t even introduced to acid at that time, but the whole house was on acid. It was a party.

Jim lived right behind, on the hill down below. He loved Eric. I was playing the piano – it was at the time that we were still creating the music to “Spill the Wine”, and Eric and I were sitting at the piano while everybody else was partying. The next thing I know Jim jumped up on the piano. I didn’t even know who he was. I didn’t know a lot of the American artists back in those days. I knew the British Invasion, the people who were at the house, but I didn’t know who Jim Morrison was, or Lydia Pense. I really didn’t know.

This guy, who was Jim Morrison, had a Superman outfit on, and he kicked over the lid on our hands. We moved our hands out of the way just in time. Eric jumped off the piano, ran up to the room upstairs, came downstairs, shot a gun. He shot the chandeliers out with his gun, and nobody ducked. I knew everybody was on some strange drugs. I’m the only one that ducked [laughs]. It was a strange thing. He shot the chandeliers, and as I say nobody ducked.

Jim Morrison backed up into the fireplace. What I did was I put my finger on his chest, on that Superman logo, and I said, “You need to quit, whoever you are.” Because he kept rolling his fist around, and said, “I bet you’d like to hit me.” I knew he was high, and I said, “You’d better cool it man” [laughs]. So he backed up when I touched him, and I guess I looked like I hit him but I didn’t. Like I said, I touched his chest, and I moved my body back with my finger, and I guess it did looked like I struck him, but I didn’t hit him, because I never hit people, not with my hands having to play piano [laughs]. I didn’t have insurance on my hands at the time. I never hit anybody. If I was going to hit him, it would’ve been with a bat or something.

But he backed up into the fireplace, and this young lady came running in the house, to the fireplace, and said, “Is James here? Where is James?” I said, “Are you looking for that guy?” “Yeah”, and she picked him up like he was piece of paper, and took him out of the house, took him, I guess, back to his house. Then that’s when I found out the story about who he was. “Oh, that guy!” I didn’t know.

The only American artists I knew back in those days… Well, we knew Jimi Hendrix. You know, Jimi’s connection with The Animals, Eric being our lead singer, and Chas Chandler of The Animals producing his first album, and he and Eric being really good friends. He jammed with us the night before he passed away. We were the last band he jammed with. We used to pass each other back in the day, when he was playing with The Isley Brothers, Little Richard. And then we were on the road around the Seattle area, playing all the hole in the wall clubs, and we passed each other many times back in the ’60’s. We pretty much knew each other. We knew him when he was just a back-up player, doing exactly what we were doing, playing the same kind of music. R&B stuff.

JM: What do you remember about the night you jammed with Jimi Hendrix shortly before he passed away?

LJ: He was pretty cool, just the same person that we knew in L.A. in the past. My manager and producer Jerry Goldstein had this bungalow, and he always came there. As a matter of fact, one of our first gigs that we did was a festival with Jimi Hendrix, Mother Earth. It was a whole bunch of people – Marvin Gaye was on that one. A lot of people were on that – The Grass Roots. It was a three-day festival. [JM: This must’ve been the The Newport 69 Festival]

He was the same guy. Just shy and mellow. He came down Tuesday night, didn’t bring his guitar. I asked him, “Man, are you going to bring your guitar? You should jam with us.” So he did. He brought his guitar the next night, which was Wednesday. We were at Ronnie Scott’s at the time, in England. We had like five nights there. We were playing in the middle level, and Osabisa was playing down below. I would go down there to listen to those guys play.

But then Jimi came down the next night and we jammed on Memphis Slim’s “Mother Earth”. The only scary part that seemed weird to me is that afterwards, when he goes back to his flat or wherever he was living, and we get this call from Monika saying that Jimi has vomiting and she didn’t know what to do. We were telling her to call the ambulance, and she was panicking because she didn’t want to get in trouble. She was still going to school. She wasn’t a nurse – she didn’t know what to do. She didn’t want to get busted with the drugs in the room. The law back then was a little bit more strict than it is today. Nobody was mad at her. She couldn’t help it, and she didn’t know all she had to do was turn him over. He could’ve probably survived it had he turned over, but nobody really knew what was going on. We didn’t have a cellphone where you can take a picture, or “go live”. We just didn’t have access to all that.

JM: The album The World Is a Ghetto was a huge hit for the band, and went to Number One. What are your reflections on that particular album?

LJ: Like most of our songs that we wrote, everything was basically improvised, pretty much like how Eric taught us how to improvise on the stage back in the day. Whatever you do onstage, you can go in the studio and do the same thing. Just turn on the tape. If you don’t, then you’re going to miss everything, because we cannot repeat it. My take on it is that it was something that just came out of our heads, that came off the streets. Everything that we wrote pertained to the streets. We would just take it and pick up the tempo, and write some words according to what was going on at the time. The music just came naturally.

The World Is a Ghetto was basically about us connecting with the world like troubadours, making people aware of what was going on, especially those that never had the chance to travel outside their town or city. They don’t know what’s going on. A lot of people that don’t travel are afraid of other people [laughs], or if they stay in one city with one race of people, they are afraid to connect with another race of people because they don’t know how they are, however they’ve seen them on TV. They don’t know. The World Is a Ghetto was something pretty much related to that issue, in its own way, without being political. Because we never wanted to ever be involved in any type of politics.

JM: What do you remember about the recording of the song “Low Rider”? Did it also come from a jam?

LJ: It was all a jam. Our saxophone player Charles Miller came in, and he had just bough a lowrider car [laughs], you know, a nice Chevy car. It was time to go into the studio, and he drove the car to the studio, came in and had a bottle of tequila. We already had the track already made, and he sat down on the bench – I’ll never forget – and he had a lemon, he had salt, and some shot glasses. Of course I took a shot with him. He sat down and put his headphones on. “Charlie, you’ll like this!”

He started listening to it, and we knew how he was. He could take a song and make it funny, make it street, whatever it was he would make it happen. And he did. He just started singing it with that attitude. Like we always do, we were rolling the tape. If you don’t, they you’re going to miss it. So we always had the tape running. We never said, “Are you ready?” He just sat down and put his phones on, there was a mike there, and we just turned the tape on. And there it was right there. He had it. It was like magic [laughs].

By the way, before the song actually came out we filmed the Duke’s lowriders and the Imperials lowriders. They were pretty much rival car clubs back in those days. We gave them a copy of a whole bunch of cassettes while we were filming. We took those films and used it as our backdrop whenever we would play the song onstage. We took the film all the way to New York, to Japan, to Germany. People had never even seen a lowrider back then. Except from California to Albuquerque they knew about lowriders. But beyond that no one had ever seen it. People went into shock [laughs] when they saw all these cars hopping up and down. They just didn’t know what to make of it. We were the first to introduce it, not to mention the song.

JM: What advice would you give to an aspiring musician?

LJ: Well, if you’re going to really play music, don’t drive yourself and other people crazy not being committed [laughs]. Commit yourself, and learn the piano first of all – because that’s the mother of all instruments – before singing, before guitar, before bass, or any other instrument, even violin. Learn the piano, because that will help you know all the fundamentals of music for all the other instruments, including your voice.

Also, I would advise if you’re going to really get involved in the music, get involved in the music business as well. Learn the business. Learn how you get paid [laughs]. That’s the bottom line. I don’t have to go into details about that. Learn how you get paid.

JM: Do you see any path that would lead to you playing together with the other members of WAR from back in the ’70’s?

LJ: Not really. That’s pretty much like if I would get back with my ex-wife again, which I have no plan to. No plans at all. But we did make beautiful music together, which is our children that we had, pretty much like a marriage, because we did have a marriage. I still love the guys, but we moved on from each other. And it’s been so long – out of sight, out of mind.

I can’t really ever say we never will, because as we get older life seems to turn different avenues all the time for one another. So I can never say never, because you never know if the right opportunity would come around. When I say opportunity, it might be the right money – who knows? It could be an assortment of a lot of different things. I don’t know, I really can’t tell you. Again, I wouldn’t say never.

JM: Well, personally I think WAR should be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Maybe that’s an occasion…

LJ: That’s one way. I’m sure they would make us play. That’s a thought.

Let’s put it this way. If it’s the right opportunity, and we have a good offer, then we could work out something. As long as it’s not something that we have to do all the time. So I don’t know. I really don’t know. That’s a hard question.

JM: Do you remember playing in Santa Barbara over the years?

LJ: Yes, I do. We played the Bowl in, maybe the ’90’s or the ’80’s. We did do the Bowl.

You have to also understand that I lived in Santa Barbara in the ’60’s. I lived there for five years, when the original guitarist Howard Scott went into the Army. I met my first wife at a club in Oxnard where all the soldiers would go.

On Haley Street there was a club there Sneaky Pete’s or Speakeasy – I forget the name of it, it’s been so long. It was a happening place. And when I was living there I used to play jazz at an Italian club owned by a Madam [laughs]. A lady madam. I was in this band and we would do shows. I was just waiting for Howard to come back so we could put the band back together back in L.A. But that’s where I lived. I lived there a long time. On Figueroa Street I played the Sportsman. There was a lot of jazz going on back then. There was a jazz club right across the pond where the graveyards are – Falcon Lounge. It was a really nice one. There were a lot of jazz clubs back then, and I had the opportunity to go to all of them. I lived there a long time. I saw Strawberry Alarm Clock and the Chambers Brothers at the Earl Warren Showgrounds. That was a great show.

JM: I didn’t realize you had such a Santa Barbara connection.

LJ: Yeah. I used to live off of Milpas, on a street called Mason. There’s a lot of factories around there. It was factories then, but now even more. There’s probably two or three houses now [laughs]. That’s where I lived in a little house. I called it “running away from L.A”. But I left and came back to L.A. real quick, after five years.

One of my closest friends Ray Estrada – he’s passed away, but he used to sing the Spanish part on “The Cisco Kid”. He was the one who turned me on to all of the clubs there, because he also played jazz guitar. We had a band together, so when I went back to L.A. the band got back together, and we started recording with Eric and went from there, I made sure that Ray came down and put his Spanish part on there. You know, to show him some gratitude. His daughter to this very day is very happy about that, that I did that. I’m glad she’s happy. I don’t even think she was born then, but she found out about it as she got older. As far as she was concerned, her dad was a star. That’s good. She’s forever grateful.

Discussion

No comments for “Interview: Lonnie Jordan”