Jimmy Webb’s songwriting credits are quite remarkable. He is most closely associated with Glen Campbell, who sang the definitive versions of Webb’s songs “By the Time I Get to Phoenix”, “Wichita Lineman”, “Galveston”, and more. (A lesser known gem and Music Illuminati favorite is “You Might As Well Smile” from Campbell’s 1974 album Reunion: The Songs of Jimmy Webb.) Other songwriting credits include “Up, Up and Away” (The Fifth Dimension), “MacArthur Park” (Richard Harris, Waylon Jennings, Donna Summer), “All I Know” (Art Garfunkel), and “Highwayman” (The Highwaymen). Other artists who have recorded and/or performed his songs include Linda Ronstadt, Barbra Streisand, and Frank Sinatra. Webb has also released his own wonderful albums over the years, most recently 2013’s Still Within the Sound of My Voice.

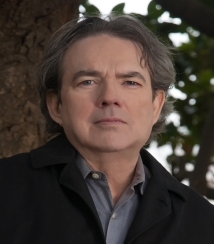

This interview was for a preview article for the concert by Webb and Karla Bonoff at the Lobero Theatre in Santa Barbara on 6/7/14. It was done by phone on 5/21/14. (Jessica Walker photo)

Jeff Moehlis: What can we look forward to at the upcoming show?

Jimmy Webb: My show is entertainment. I play a lot of hit songs. I also furnish a kind of anecdotal backdrop to some of that, to the way the business works. It definitely has its humorous side. Some truly crazy things happened to me when I sort of stumbled onstage in this business. When I got the idea that I wanted to be a songwriter I was fourteen years old, and I was plowing a field of wheat in the panhandle of Oklahoma. And four years later I had a recording on the radio stations by Glen Campbell, who was probably the greatest vocalist of our generation. Some people might say, “I think Harry Nilsson was.” Harry Nilsson was as good a friend as I’ve ever had in my life. We were extremely close, and I rate him very nearly the top vocalist that I ever heard. But certainly Glen was up there in the same rarified atmosphere.

I went from fourteen years old plowing fields, somehow a magical transformation took place, and I found myself in this world of big stars and people like Mr. Sinatra, who took an interest in me, Liza Minelli took an interest in my career, as well as Barbra Streisand and many, many others. I would say that I have a fairly deep background in this business, and I share that with the audience. And it’s meant to be entertaining. It’s not maudlin, it’s not boring, it’s not old fogey stuff.

My co-star is Karla Bonoff. We’ve been out many, many times together. We’ve shared a musical history with Linda Ronstadt, both of us having numerous recordings by Linda. We do some work together onstage, but mostly she does her show, I do my show. It’s a good mix. It’s two completely different voices, different textures, different careers, but all familiar music. People know that they’re in the right place when they’re at our concert.

JM: Speaking of Karla, do you have a favorite song that she wrote?

JW: I do. I really love “All My Life”. But there are so many songs, and she’s so well regarded, extremely well regarded in fact among the people who know what songwriting is about. And it’s nice to have someone on the program who can actually sing, as well. She has a Linda Ronstadt-like beautiful soprano voice. I’m more the songwriter-singer type, and nobody has ever rhapsodized about my vocal quality. I think that she’s my saving grace. I adore her and her songs. We’re really a good partnership. I just played a few gigs with her in the Washington state, Oregon area. She had her dog along with her, and her guitarist/friend Nina.

I think a little more than a year ago… it’s hard to believe because it was so far away on the geographical map that I tend to think that it was a long time ago, but it wasn’t. We toured Japan together, and that was really [laughs] kind of bizarre. Singing songs in English, until you find out that most Japanese do speak a good bit of English. You find out that they understand more sometimes than you would believe. And that they’re extremely emotional people. We’re taught that they’re very unemotional, and I found that their coolness is basically a charade that they indulge in to protect their emotions, because they’re extremely emotional people. Music brings that out in people. Their true feelings tend to surface.

I always go out after the gig, shake people’s hands, get to know them, listen to their stories. I mean, if they’re going to listen to mine, I should be willing to listen to theirs. I find that, by and large, it’s an opportunity for them to vent sometimes things that they’ve been sitting on for a long time. So it’s good for everybody!

JM: You mentioned Glen Campbell, and of course some of your best known songs were sung by him. When did you finally get to meet him, and what was that like?

JW: We had a couple of records on the charts before we met. It was strange, really, to have spoken to him on the phone and to have had at least one big record, “By the Time I Get to Phoenix”, which he won a Grammy for Best Male Vocal Performance in 1967, and we hadn’t met. It was like, “We should get together sometime. Play some songs, or something.”

It turned out to be a very off-the-wall thing where I ended up in the studio one day doing a commercial, just playing on a commercial, and he was there. I recognized him, of course, because I saw him on television like everybody else. I was really excited. I was a complete hippie, whacked-out kind of a guy. I had hair down to my shoulders, and at the time I wore a yak vest [laughs]. He was very turned out, always very polished and wore a suit on television and stuff like that. In those days the music business was very polarized, with the hairy guys on one side and the clean-cut guys on the other side. Well, he was one of the clean-cut guys. I walked over to him, and I said, “Mr. Campbell, I’d like to introduce…” And he looked at me, without even letting me finish, and he said, “When are you going to get a haircut?” [laughs] That was the very first thing he said to me. Years later he would deny that, say, “Oh, I never said that to you.” But that’s exactly what he said.

So we were kind of on not the same course politically, because he tended to be conservative, and was good friends with Bob Hope and John Wayne, and people like that who were very Orange County, and very Republican, and I was so not that. And so against the war, and was writing music that was subversive in the extreme. A lot of people don’t know that, but that’s where I was coming from. Somehow or other we formed a partnership that lasted almost fifty years. We made a lot of records together, we toured together. It was a pleasure to play live onstage with him. He was remarkable. Nobody could touch him with a guitar in his hand, and his voice was a marvel. It was a five octave, completely flexible instrument with no breaks between his chest and his head voice. Very much like Nilsson. They both had a fluidity to them. And we was funny. He knew, like, ten thousand jokes. I mean, most of them were kind of dumb, like “It’s cold outside. I saw a chicken with a cape on.” You know, that’s a Glen Campbell joke. I know… [laughs] But he knew a million of them, as the old vaudeville expression goes. He was always fun to be around.

And he went through some real changes. I saw him go from a very, very conservative guy to being pretty whacked-out there on different kinds of substances. He had some crazy relationships, and somehow or other came back to Earth, and, I thought, finished his career on a high note. I don’t think that you’ll ever see anyone else with Stage 4 Alzheimer’s touring the world three times, and going out every night and singing and playing their hits in a very, very acceptable way. There were certain nights when people had no idea that Glen had any problems with his memory. Because once he got in the groove with the guitar and the song it was all kind of automatic.

JM: I saw him at the same venue where you’ll be playing, and it was great. I really enjoyed it.

JW: That’s great. I’m glad to hear that. A lot of people really enjoyed it. Every once in a while somebody would grumble. It was funny. He went down to Australia a couple of times, and one night he made a mistake. He sang “Wichita Lineman”, and then he just turned to the band and kicked it off again, he sang it again. He sang it twice. He started to sing it again, and his kids were saying, “Dad, you’ve already done that twice.” But the crowd, because the Australians are so terrific, they got up on their feet and they said, “Sing it again!” [laughs] Ten thousand people yelling, “Again! Again!” A lot of it kind of depended on your attitude when you went in to see him. But if you went in with a full heart, and understanding what the situation was, he did not disappoint as an artist. I don’t think there’s very many people who could do that.

JM: What advice would you give to an aspiring songwriter or aspiring musician?

JW: Give up the idea and go back to the farm [laughs]. No, that’s a joke. It’s a joke based on having survived the school of hard knocks.

I’m chairman of The Songwriters Hall of Fame, and I also sit on the Board of Directors at ASCAP. I’m actually Vice Chair at ASCAP, and we’ve been going through a heck of a time here in the last fifteen years or so trying to defend a small bit of turf, a safe ground where songwriters can create and get paid for what they do. Because nobody will do anything for nothing. So songwriters have definitely been threatened by digital interests, by companies like Pandora that want to pay next-to-dirt for using music. We have somebody like Adele who has six million plays and gets a check for $20,000. I mean, it’s outrageously ridiculous. It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that over time, people are going to become less interested in being recording artists and songwriters. Most songwriters don’t make a lot of money, and never have made a lot of money. In the heyday of Elvis Presley, for instance, we made a penny on one side of a record that sold for 99 cents or a dollar. The songwriter would make a penny. So if a song was a hit and sold a million records, the songwriter would make $10,000. The record company would make a million, which they would split 8% probably to the artist, but the rest they would keep. Even in the heyday of records, of mechanicals – which really now when you say mechanicals it’s a synonym for downloads – what we’re paid for downloads now is so much less than a penny, it’s not even worth talking about. You’re into the mils, you’re into counting mils.

So it’s been very, very tough to sustain a community, and also a tradition of songwriting, when fewer and fewer people are really capable of making a living doing it. It’s ironic that more people than ever want to be in the music business, but at the same time the economics, as configured by the digital interests online, which is where the business is slowly but surely moving… The CD has stuck around at least ten years longer than it was expected to, because a lot of people still like to own things. They love their records with the big covers and the artwork and everything. You see a resurgence in the vinyl market, the 33 1/3 market. I just found out that my last two records are going to be pressed on vinyl, because they did pretty well on CD, largely because I had a largess of talent on those records. I had Billy Joel, I had Jackson Browne, Willie Nelson, Lyle Lovett, Lucinda Williams, I had Joe Cocker, on the last record I got The Jordanaires back together. I had people like Vince Gill, Amy Grant, Keith Urban, Michael McDonald. I really don’t want to leave anybody out, but I had superstars all over those records, so now they’re going to be pressed on acrylic. It’s a sign that just because some mucky-muck at a digital radio station says, “People aren’t interested in CDs anymore”, well, that’s not necessarily true. It sounds good, and it’s good for them because they don’t want people to be interested in CDs, and they don’t really want people to be interested in vinyl records. But people like to own things, they like to be able to stick things up on the wall, and decorate their dorm room with posters. That’s just the way people are.

I’m not a Luddite. I have a Mac Air, and I use a computer constantly. In fact, I’m writing a book on my Mac Air. You can’t dismiss me and thousands of others like me as being anti-technology, and old farts who want the world to go back to the way it was. That’s not true. We merely recognize the fact that all the formats that are now “obsolete”, they’re not obsolete. People still like to have their records in their bookcase, and they always will like to do that. Like the caveman used to like to collect their spears and put them in a certain place in the cave. It’s so deeply embedded in human nature that it’s going to take more than a pronouncement from someone that such and such is true.

In the meantime, we were almost pirated out of existence. Billions and billions and billions of dollars worth of music was traded illegally, and people thought it was funny. It was a cool thing to do. But it actually affected real, live human beings in a really negative way. And it hasn’t been good for the music business, because the music isn’t any better. If anything it’s worse. That’s my little speech.

JM: Here’s an obscure question for you. I read that Iggy Pop recorded his album Kill City at your home studio back in the ’70’s. How did that come about?

JW: That’s right! Well, I had a studio at home. He was a good guy. He would come up, and I didn’t really charge anything [laughs].

But I had a beautiful studio. I had two Scully 16-Tracks and a board. It was a full-fledged recording studio with a control room. It had a fireplace. I’ll never forget the day when the bees came down the chimney. The bees swarmed down the chimney and attached themselves to one of the mic stands. Somebody came running into the house and said, “There’s bees in the studio!” I said, “You’re kidding.” We went out and there were literally like millions of bees, all glommed up together, you know what I mean, in a swarm. They’re on this mic stand, and I said, “Turn the mic on!” I said, “Let’s roll some tape.” [laughs] And so we taped the bees for a half an hour. We’ve still got that somewhere.

I had inputs built into the walls of every room of my house, so when I would have a party I would put discretely placed microphones in all the rooms, and then run the 16-track. And I’d have everyone at the party on tape, talking at the same time, and I could pull up different people saying different things. So I still have those tapes, at my 30th birthday party. I had Roman Polanski there, and, oh my God, Joan Baez was there, Kinky Friedman, and Brian Wilson, Harry Nilsson of course. Just a great conglomeration of talent and energy. Somewhere they’re all on tape. I’ve never listened… Who wants to sit and listen to a party, you know? But I recorded it.

So Kinky used to come up, Ringo Starr used to come up, Harry would cut there, Larry Coryell cut there. It was a very, very select group of people. I wasn’t taking ads. I wasn’t advertising. I made my second album And So On there, and I actually got a Stereo Review award for Album of the Year from them. That was back when Stereo Review meant something. Of course, they eventually went out of business because, I don’t know, high fidelity, hi-fi, the whole idea of high-end electronic gear kind of was usurped by the Walkman, really. It became mobility, it became accessibility instead of fidelity, if you will. But it’s interesting to know that some people are getting back to fidelity. People who are interested in acrylic records, pressings, they’re interested in fidelity. It’s young people. It’s guys your age or younger who are doing this. It’s not us. And you know you “us” is. We’re all the old hippies. But it’s not really us. We’re not clamoring for 33 1/3 RPM, it’s a much younger group.

So anyway, there’s the answer to your question. He came and went. I’m not sure if I ever really heard the whole record.

We made some good records there, actually. I made about three or four there myself, and I did the soundtrack for Tombstone [JM: actually, the official name is Doc], the Frank Perry film that was kind of the first revisionist… you’ll have to go to film school to get this verified, but if not the first, it was one of the first revisionist Westerns about Wyatt Earp and his brothers, the truth behind the fact that they were really gamblers and card sharks, kind of disreputable people. Frank Perry was a great filmmaker. You can’t know your films without knowing the films that he did with his wife.

JM: What are your plans, musical or otherwise, for the near future?

JW: I’m touring, and I’ve been doing more. It may seem hard to believe, but I’m getting better at it. My voice is getting stronger, not weaker, as I’m getting older, because I have no discernible bad habits. I don’t drink, I don’t smoke, I don’t do anything that’s detrimental to my voice. My voice has really blossomed. It’s very strong. Touring will wear anybody’s voice down. I mean, it will wear anybody down, I don’t care who you are. But if I get a clean start, not singing for two or three days, my voice is real clear, real strong, in tune. I offer my last two albums as evidence of the fact that I’m a much better singer than I was when I started.

What I’d really like to do… I’m kind of busy right now, writing a book about the California years. I’m writing it for St. Martin’s, so it’s the real deal and I have to take the writing seriously and put time in. Meanwhile I’m dashing out and doing my odd concert, like this flight out to Santa Barbara. Which, by the way, my son Charles Webb graduated from the University of California at Santa Barbara. He still lives there. He loves it there. He would love it if he got his name in the paper. He’s a great guy. He lives in a co-op, and he loves living in a co-op. He makes spaghetti and meatballs every Thursday night. But, anyway, I make these little runs out. I may do four or five gigs at a time, or it may just be a one-off like this one, which is a very, very special gig to me. It’s very special. I’d like to see everybody show up, because I’m going to do a damn good show.

In the back of my mind is that my next move will be another album. I still have a record deal. I mean, I’m very, very fortunate at my age, having never really had a punch out Top 40 album, Top 10 album, I’ve never had them, I’ve always been a boutique artist, but I’ve always managed to have a label. And I still have one, and I would like to do an album of all original songs, which is something that I haven’t done in a long time. I have a lot of these songs, some are written, some are half-written, some are just twinkles in my eye. They’re in my notebooks in various forms. That’s the way I work. If anyone’s read my book, Tunesmith, which is about songwriting, they know that I’m a great advocate for the notebook, and I always have a notebook in my hand and a pen nearby, because that’s the way you get all the good stuff.

And so, I’m working on these ideas for songs, and concepts for the album itself. I’m extremely upset by the fact that it seems like mankind is bent on its own destruction. This is something that I cannot comprehend. I can’t comprehend a kind of petroleum-based economy, open-ended expansion that consumes all the resources that we have, and at the same time is exponentially doubling and tripling the population so that eventually the whole freaking mess falls off of a cliff. Cannot understand it. My generation, we wrote about things like this. We got angry and we wrote about things like this. I think that that’s not so much the trend today. The trend is, you know, let’s party. It’s happening, but let’s party while the Titanic goes down. I really have some things I would like to say to the world. If this might by some misfortune turn out to be my last record, I really feel like I have some things I need to get off my chest. So that’s where I want to go. It’s a solo album. I’m even thinking maybe going back and possibly asking Linda Ronstadt to produce or co-produce, because I think she produced one of my best records, Suspending Disbelief. So that’s kind of where I’m headed record-wise.

I’m also determined to get a Broadway show on. I came back here thirty years ago to do that, and I’ve been very close. I’ve been as close as technical rehearsals, the Friday before the opening. I’ve had the show canceled out from under me, three days before the opening. I’ve literally spent years working on musicals. The last one I was on for four years, and rug was jerked out from under me. It can be very cruel, very disturbing. One has to pick oneself up, dust oneself off, and jump back into the fray. Because it’s very difficult. It’s probably the most difficult thing to do in the entertainment business. I would equate it with making a major film. It may be even trickier to get a musical on. I admire anyone, whether the show runs or not, I admire anyone who’s able to open the curtain on opening night and say, “Here’s our show.” That is something you can be proud of, no matter what happens. Since it’s so difficult to do.

That’s what I’m looking at. That’s my future. I’m still very excited about music. I haven’t cooled on it. I love performing. I wish I had another fifty years. I know I don’t, but I feel like I’m just getting warmed up.

Jimmy…..I have not the words to describe how monumental you have been to the American music scene. Suffice it to say, you have touched souls you never knew and changed hearts, with the stroke of a pen to staff paper……thank you, from a kindred spirit who wants to see your ass on Broadway, dammit!!! All the best to you and yours,

Shawnice