Ian Anderson is the frontman / singer / songwriter / flautist / acoustic guitarist / musical mastermind for Jethro Tull, which is celebrating its 50th year. Anderson is the only member who has been with the band since its beginnings.

Next up was Jethro Tull’s classic album Aqualung, released in 1971 and regarded by many to be the band’s best. This included the signature tunes “Aqualung”, “Locomotive Breath”, and “Cross-Eyed Mary”.

Jethro Tull followed with two concept albums, both of which reached No. 1 in the US charts: 1972’s Thick as a Brick, and 1973’s A Passion Play. They released many more albums, notable ones including the compilation Living in the Past (1972), War Child (1974), Minstrel in the Gallery (1975), Songs from the Wood (1977), and Crest of a Knave (1987) which somewhat controversially beat out Metallica for the Grammy Award for Best Hard Rock/Heavy Metal Performance.

This interview was for a preview article for noozhawk.com for Jethro Tull’s concert at Vina Robles Amphitheatre in Paso Robles, CA on 6/3/18. It was done by phone on 5/1/18.

Jeff Moehlis: What are some of memories you have of Jethro Tull’s first tour of America?

Ian Anderson: Well, good and bad. I think the first show was either at the Fillmore East or maybe the Boston Tea Party. It was an important gig, the first thing we ever did, so it was pretty nerve-racking. There was no kind of warm-up of maybe playing in a few Midwestern towns in a pub or a club somewhere. It was straight into the deep end playing two of the most iconic venues in that period of time – the Boston Tea Party where Dan Law was the promoter, and Bill Graham, of course, at the Fillmore East. So these were pretty scary places. You were in at the deep end, straightaway you were going to be judged by a very savvy audience and by two of the biggest promoters that have ever been in the USA.

I guess it went OK, otherwise we would’ve been on the next flight home. But there was a lot of hanging around. We didn’t really have a lot of work, so there were days when we were just sitting in some terrible, terrible hotel sharing rooms and waiting for our manager to tells us we had another gig somewhere. So it was 13 weeks of being away from the UK to play maybe three weeks worth of shows [laughs]. It was a toughie.

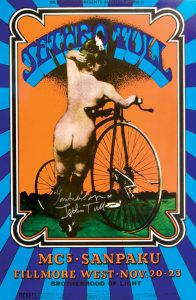

I think actually on that tour we supported Led Zeppelin in a couple of places, and memorably we played in Seattle with a band we were warned not to go anywhere near, not to talk to them because they were very violent and aggressive and scary. Quite nervously we did our soundcheck and waiting to go on before the MC5. You know, there were pretty scary onstage, but a couple of months later we were playing again in the USA and some of the guys from the MC5 came to see us in Detroit and were real pussycats, really friendly. They remembered us, and we were getting a bit more well-known and playing in bigger venues, and they came backstage to say “Hi”.

And I met people like Mountain – Leslie West and Felix Pappalardi from the band Mountain. They subsequently went on to tour with Jethro Tull a couple of times. You know, there were lots of opportunities, I suppose, to see some of the great bands, sometimes to work with them, sometimes just being in the same hotel [laughs]. It was memorable, but as I say, good memories and bad memories.

JM: The tour eventually found its way to California. What were your initial impressions of California when you came?

IA: Generally speaking – I suppose it’s partly geographical – there’s an easier affinity between us Brits and, perhaps, New England. It’s partly geographic, but it’s also, I guess, because of a bigger concentration of immigration from England, Scotland, and Ireland, into what became the New England states and Nova Scotia, and even down the Eastern Seaboard, too. So that’s always seemed an easier fit.

Once we got to the West Coast, everyone said, “You’ll love California. You’ll love San Francisco. You’ll love Los Angeles.” I suppose because it was talked up as being so great – fabulous weather, everything’s kind of laid back, and a lot of fun and palm trees and stuff – but I’m afraid I didn’t really take to it at all. I just hid in my hotel room for the first few years when I was in California [laughs]. I mean, of course we made the odd excursion out to Fisherman’s Wharf out in San Francisco, or to some club – I think the Whisky – in L.A. We sort of had a little bit of a look at things. We sort of sniffed the air. But I never felt very comfortable, particularly in Los Angeles.

There were other parts of California I was more charmed by. I quite liked San Diego. I quite liked San Francisco, except for the experience of playing there in the early days, because it was the end of the hippie era and everybody was just out of their brains on whatever it was they were smoking or taking. I felt really outside all of that. I didn’t enjoy playing at the Fillmore West, for example. I really hated that. It was a very uncomfortable experience. I just felt like I was from Mars, you know, having nothing in common with the people in the audience who were there for a different kind of a celebration. Whereas playing at the Fillmore East was a little easier because it was a New York crowd, and they seemed a bit more awake and a bit more alert, and a bit more intent on listening to and judging the music. So I always found the West Coast to be difficult.

But later on, it sort of changed around a bit. These days I don’t even stay in New York. If we have a show in New York we stay out of town, drive in for soundcheck, play the show, drive out of town as soon as we leave the theater, and stay somewhere 30, 40, 50 miles away in order to get away from New York. I feel claustrophobic and trapped in New York City, whereas I’m much more at ease now in California than I was. There’s little more sense of space. I still wouldn’t like to be stuck on any of the major freeways around Los Angeles at rush hour [laughs]. But it’s kind of easier.

Your perspective changes a little bit as you repeatedly go to places. Several places I used to like I don’t like anymore, and some places that I really felt uncomfortable in now I quite enjoy going there. It just changes around.

JM: I have a music question for you next. What inspired you to incorporate the flute into the music of Jethro Tull?

IA: Well, desperation, really. I was a not very good guitar player when I was in my teens, and when I was about 18 years old I heard Eric Clapton for the first time, when he joined John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. I realized that this guy was so far ahead of the pack, there was no point in trying to catch up. I was never going to be that good. Of course, then I heard about Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck and Ritchie Blackmore and other hotshots down in London who were doing sessions. It seemed the world was getting pretty crowded with very innovative and exciting guitar players. And then, of course, along came Jimi Hendrix, too, to make it impossible.

So I looked around for something else to play. I suppose for reasons of practicality I had a harmonica, and learned to play a blues harmonica. And I bought a flute. I traded in my Fender Stratocaster for a cheap student-model flute and a Shure Unidyne III microphone, and armed with these two new things set off the South of England to try and give at least a year to be a professional musician.

I didn’t do anything with the flute for the first few months, until around December of ’67, because we were approaching Christmas. I got the flute out and managed to get a few notes out of it, and then a few more. By the end of January, when Jethro Tull became Jethro Tull, I was playing the flute in quite a few pieces of music during the show. And then improvising. I tried to translate what I did on the guitar into the flute. It was just a different technique, different instrument, and by the time we recorded our first album, which I think from memory was about July of ’68, I mean I’d only been playing for about 7 months. At the time Jethro Tull became noticed, and there was a bit of a buzz about the band, I’d only been playing the flute, I suppose, for about 2 or 3 months. I made my name and reputation as a flute player really under totally false pretenses, because I never had a lesson in my life, and I really knew nothing about the flute, including for sure where to put my fingers on the keys or anything about it at all. It was just being self-taught, and fumbling around to try to find some things to do with it.

There weren’t a lot of flute players around in those days. It wasn’t unheard of in pop music or in jazz or in folk music, of course. But it certainly wasn’t featured in any blues bands who were playing around at the time. I was the only flute player in terms of rock music until rock music developed, particularly in ’69, when the term “progressive rock” was first coined by the British music press. I had it pretty much to myself. There was a flute player in the Moody Blues, and Chris Wood in Traffic played flute a bit onstage. He was a saxophone player, really. And somebody in King Crimson, I think, also played a flute. And then, of course, along came Genesis, and Peter Gabriel played a flute, although I think wisely he decided not to continue with that. So for all of that period of time during the late ’60’s and early ’70’s I wasn’t having a lot of competition out there. So it seemed like a very wise choice to get away from the guitar and take up an instrument that was not very common in that musical genre.

JM: One of my favorite Jethro Tull albums is Benefit, which I think has been overshadowed by the one that came next. Incidentally, Benefit came out in the U.S. exactly 48 years ago today. When you look back at that particular album, what are your reflections on it and its role in the evolution of the Jethro Tull sound?

IA: There have been lots of albums that, I think, in their different periods have kind of set the bar for a change of genre in a different peak in the band’s career. Most notably, I suppose for me personally, probably the second album Stand Up is the one that marks the departure from the imitative kind of simple blues thing that we began with to finding more influences, more eclectic musical settings for simple songs that I was writing.

By the time we got to Aqualung, another album that certainly made a big change for the band’s fortunes… It wasn’t instantly a huge hit out of the box, but it progressively sold over the next couple of years, particularly, but then to this day I suppose it is the biggest selling Jethro Tull album. And Thick as a Brick, which followed it, was the scary one, because after Aqualung what do you do? It seemed necessary to try something a bit braver, and Thick as a Brick was not something that I think our record company or our management were very comfortable with. They thought this was maybe a step to far, but I thought let’s push the boundaries a bit, and see if we can drag our fans down that rather more elaborate direction.

And by putting it in a slightly comedic context, a slightly surreal humor environment, that I think was the wise and forgiving way of embarking upon that music. It was serious, but yet it was lighthearted and a bit of fun. So hopefully I wouldn’t be accused of being too deadpan, because bands like Yes and the early Genesis were incredibly serious. There was no humor attached to any of that, all of it was sort of showing off them being terribly serious about their music, whereas we were just having fun with the idea. We weren’t such good musicians as them, but we could put it in a more theatrical setting and have a little fun with putting an album and then a tour together which was not something that everybody else was doing at that point. I think maybe Alice Cooper had just begun, and that was the only other really theatrical act around at the time. That was a good thing to be part of, the feeling, particularly in live performance, that you were bringing elements in to make it more of a show, more of an experience that involved other elements, not just standing onstage playing your music.

JM: Speaking of bringing humor into the music, I read that you were a big fan of Monty Python, and that Jethro Tull even helped to finance the Holy Grail movie. Could you tell us more about your Monty Python connection, and how they influenced what you were doing?

IA: I think Monty Python were what you might argue were the third generation of British humor. They were the TV generation. Prior to that there’d been the radio generation of British humor, which really was the surreal humor that came out of a number of precursors. Some of the guys from Monty Python were into radio before they managed to get onto TV. It has a tradition, you see, that kind of slightly weird, surreal humor. It’s something very British, and goes back into some elements of humor that began even to the ’20’s and 30’s in music, and transferred into that kind of slightly wacky, weird radio stuff through programs like The Goon Show and Round the Horne, and other radio things of the ’50’s and ’60’s.

And then Python came along, and of course after they’d had their run at it essentially in the early ’70’s, it evolved into other British humor, into a number of rather surreal and weird camp kind of performances from different musical troupes, who in the tradition of Monty Python took TV by storm, at least for a while. So it’s something very British. It’s something that I think influenced us – when I say us, I mean we British musicians, not just me or Jethro Tull. It was something that I think we all kind of tuned into. We felt it was ours. We felt it was a very national form of humor. We felt it was British. Of course, it was making fun of the British most of the time, but we’re good at making fun of ourselves. So we all rather liked that.

When Monty Python were making their Holy Grail movie, and the word was no one would fund them, no one would put up they money, we in music industry – a few bands including members of Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, and me, and the managers, and folks who were involved in some of the record companies back then – we put up money to fund making the movie. To this day, I get a royalty check, which is nice to have from something that you were a part of getting it to happen.

My only regret is that Life of Brian, which was I think a bigger, more important movie than Holy Grail, we didn’t get the opportunity to invest in, because somebody told a little fib to Pythons and put up all the money, and we were excluded from the funding of Life of Brian. Traditionally in the theater, the term “angel” is the one that’s used for coming to the rescue and putting up the money for a production, and if that production is successful then traditionally you get offered the follow-up. You know, you become an investor is somebody’s life and career and commercial and artistic success, and you’re invited to participate again if it’s successful. And unfortunately we were not able to do that, so I, for one, was a bit pissed off about it. But I know for a fact that the Pythons were told a fib, because I spoke to John Cleese about it some years later and he was quite surprised that he’d been told that none of the original investors wanted to participate again. When I asked him who told him, then it became clear that a bit of subterfuge had gone on.

JM: You’re being very coy – I assume you don’t want to name who told the fib?

IA: Well, if he was alive today then I certainly would mention his name, because I feel angry about it. But I think we’ll leave the dead to their own memories that we prefer to have about them.

JM: Fair enough. As something that I perceive as humor in the music of Jethro Tull, on Passion Play there is “The Story of the Hare Who Lost His Spectacles”. I have a friend who calls that “Winnie-the-Pooh on acid”. What inspired that story, and that music?

IA: That, I have to say, was largely to do with Jeffrey Hammond. I just wanted some surreal moment… There were two sides, because we’re talking about vinyl records back then, and I wanted something that would be the end of Part 1 and the beginning of Part 2, something a little different that would separate the music in a way that gave this little hiatus between the two sides, that it would have its own rather curious and surreal identity. So Jeffrey came up with “The Story of the Hare Who Lost His Spectacles”, wrote the words, and the idea was it would be a spoken word piece and John Evans and I came up with some musical ideas and we put that together. It was Jeffrey’s baby, really. He was the one who came up with not only the words, but actually performed it, and of course when we then came to make a video that we used onstage when we did the Passion Play tours, Jeffrey was very much at the center of that as a performer.

You know, Jeffrey was one of those guys who if you met him in private life he was incredibly shy, really the antithesis of a performer. He liked to really just have a quiet life away from the glamor and the pizazz. He was embarrassed to talk to fans or strangers. I mean, he was not exactly a recluse, but just a very shy and private person. But when he walked onto the stage, he became ten times larger than life. And that was always the very exciting thing about having a guy like that in the band, who went through this metamorphosis every night [laughs]. Five minutes before he walked on he became this completely different person for the next couple of hours, which was great.

Jeffrey came to one of the shows three or four weeks ago, when we started the UK tour. He had been quite ill for the last few years. It was great to see him out of the house. He looked pretty well. I think he enjoyed the rare occasion of going out of his house and doing something, and being with other people. So I think he probably found it exhilarating, but exhausting, too. He tires quickly. But it was good to see him, and he was in good form. He contributed a little bit to the show in ways that people will see when they come to the show.

JM: I interviewed to you about two years ago, and we were talking about similarities between songs, like [Jethro Tull’s] “We Used to Know” and “Hotel California”. I mentioned to you a song by Country Joe and The Fish called “Love Machine”, which reminds me a bit of “Locomotive Breath”. Did you ever get a chance to listen to that?

IA: I think I did, because I remember you telling me about it, but I don’t recall what my conclusion was. It’s, of course, the case that people, without being directly plagiaristic… You know, you hear stuff on the radio and you’re aware of other things going on in your musical world, and you kind of half-remember little things. They all sit there somewhere in your head.

When The Eagles were on tour with Jethro Tull, actually as an opening act back in the early part of 1972, we were still at that point playing some of the music from previous albums, including the song “We Used to Know”. I guess The Eagles probably heard us playing it onstage. They may well have heard it on the radio, anyway. But I’ve never accused The Eagles of plagiarism. You know, I can see the similarities, particularly in terms of the chord sequence, the actual harmonic nature of it. But the time signature is completely different, the melody is substantially different, and the lyrics, of course, are totally different. So, for my money, The Eagles came out with one of the best and most classic pop-rock songs ever. I mean, who would not liked to have written “Hotel California”? If there’s a little bit of my song kind of in there, then I am flattered. I’m certainly not someone who would accuse them of plagiarism. I never have. Other people have continued to make that comparison to this day.

JM: My last question for you is kind of obscure. There’s a song called “Left Right” which was finally released on the Nightcap album. To my knowledge it was never recorded again, although pieces of it perhaps figured into “Baker St. Muse”. What’s the story behind that song?

IA: Well, it’s just one of those pieces. There’s lots of them over the years, particularly in the ’70’s – you know, outtakes, things that were tried, demos that were made and half-recorded in the studio. You know, a few of those were found for the Songs From the Wood album and for the 40th anniversary remix that Steven Wilson did of Heavy Horses earlier this year. So some of this stuff does find its way out there eventually, and in various states of repair, because quite often they were unfinished studio recordings.

They’re of interest, I suppose, to the fans who just simply want to hear everything, but I’m pretty guarded about it because somewhere along the line I had taken the decision as a record producer not to go further with that idea. So, whatever my reasons were at the time, it was something that you could consider as not being up to the standard, or certainly not fitting for a particular album. So I’m a little wary of going back and saying, “Oh well, we’ll release that anyway.”

It’s just something I’m told some of the fans at least are really interested in. But I have a bit of a reticence about doing this, and certainly there are things that have been put in front of me, old tapes that have been discovered, and I’ve said, “Listen, I’m sorry, but that absolutely is not something that I want people to hear.” Sometimes it’s because it’s a crap song, but it could also be because maybe somebody’s performance is really not up to the mark, and I would be embarrassed for them if that was made public. Bearing in mind, we’re talking about things quite often that are just demos, just fooling around it a preparatory state in the studio. I don’t think it’d be very fair to some people if they got to hear somebody trying out some ideas in an arrangement that didn’t work.

Discussion

No comments for “Interview: Ian Anderson 2018”