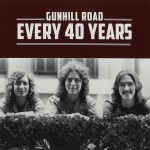

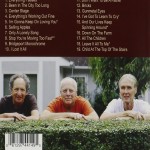

Amongst the incredible line-up of movies at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival was the world premiere of a cool documentary about the folk-rock band Gunhill Road, best known for their 1973 Top 40 hit song “Back When My Hair Was Short”. The name of the film, Every 40 Years, is a reference to the 40 year gap between the band’s heyday and their reunion that saw them performing a couple of gigs and recording a fine new album.

The film was co-directed by Eric Goldrich, the son of Gunhill Road’s pianist Steven Goldrich, who wanted to learn more about that phase of his father’s life and also to document the band’s reunion. Mixing vintage footage with new interviews with the band and associates – including Kenny Rogers who produced their first album – Every 40 Years tells the touching story of a band that tasted fleeting success, then got a chance decades later to make music together again.

There’s also a Santa Barbara connection – Gunhill Road’s singer/guitarist/songwriter Glenn Leopold lives in Santa Barbara, having moved here toward the end of a successful career in the animation industry, something he got into after the band petered out. Leopold, Steve and Eric Goldrich, and Gunhill Road bassist Paul Reisch were in town for the premiere, and the band even played their first real West Coast gig at the Red Piano afterwards.

This interview with Glenn Leopold was done by phone on 2/10/17, for an article on noozhawk.com.

Jeff Moehlis: Have you been enjoying the film festival this year?

Glenn Leopold: It’s really been interesting. I can’t say that I have a film in it, but my friend has a film in it, and I’m the subject. I’m the subject matter and not the show maker. I didn’t have to pick a bunch of films because I knew I was going to have to be practicing with the band for a few days, so I wasn’t under a lot of pressure to fill out my schedule of what movies I was going to see.

JM: I enjoyed watching the documentary Every 40 Years. Do you think it accurately captured the history and spirit of Gunhill Road?

GL: I think Eric Goldrich, who directed it, really did capture it. I think it has the feeling of those 70’s days when you didn’t know who you were going to be signed with, and what they were going to do for you, and whether the record was going to do anything. It was a whole different scene. Music has changed so much today from the way it was then. I don’t know if you can really duplicate 42nd Street – you had all these low-budget theaters there, and now of course it looks like Blade Runner or Vegas on steroids. I think it did capture the spirit of what we were doing there.

JM: I was lucky enough to catch you guys perform at the Red Piano also. What’s it like to get back together and play?

GL: The first time was in 2011, so that was really surreal because it had been like 35 years since we’d sung together. I had some trepidation at first. Paul [Reisch] and Steve [Goldrich] were practicing without me in New York, and then when I came out we did the first song, and all of a sudden the voices were blending, it was like being right back in the 70’s again. And so that was really fun.

And then we did it on stage with other people and with a big audience at the Outpost in the burbs in New Jersey, and it all clicked. That gave us the impetus to keep going from there, and maybe record again. I never thought that we’d end up with a movie, and I never thought we’d have a 19 track album. As our piano player Steve Goldrich puts it, it’s been quite a ride, and it just keeps on going.

JM: When you played at Red Piano, it was billed as your first West Coast performance in 40 years, or something. Do you have any stories about your West Coast performances during the 70’s?

GL: It’s interesting that you ask about that, because we never really played a gig on the West Coast. For some reason, and it might be a misconception on my part and maybe the record would get played a little, but I don’t think it was as big of a hit on the West Coast as it was in the Midwest and on the East Coast. So, maybe west of the Rockies it wasn’t as big of a hit.

But we never really played a gig out here. We did American Bandstand, which of course we were singing but it was lip-syncing, too. We were singing but they were playing the record. We did that with Dick Clark, and that was the year when all the tapes were destroyed, I guess in a fire. They don’t have any of that year’s shows. So that one doesn’t exist for anyone to watch, we just have a still of us with Dick Clark.

And the other thing where we actually played live, without playing the record, we played a couple of songs on Midnight Special. I want to say that after us came Slade, I think. It was in the morning, and instead of having the big audience you always saw for the big-name acts, we were playing early in the morning in front of a couple of kids from a bus tour or something, a tour of the studio in Burbank. So those are the only real gigs that we played on the West Coast, believe it or not.

JM: The band is best known for the song “Back When My Hair Was Short”. How did that song come together?

GL: There was this guy that was producing or directing a special, I think it was a documentary about the Randall’s Island Music Festival. Apparently the promoters lost money or ran off with the money or some kind of thing where it turned out to be a debacle. It was all about people getting ripped off. At one point, I was asked if I could write a song that would encompass that kind of cynicism. So that was sort of going through my brain when I was talking about people ripping off one another in “Back When My Hair Was Short”. I’m not sure that they ever made the movie, or if it ever got submitted to them, but it ended up being in the Gunhill Road repertoire.

It was the only song that Gil Roman, who was our bass player at the time, sang lead on. Because it was kind of a quirky… I don’t know if you’d call it a novelty song, but it was just kind of cynical and had a couple of drug references. And that was the song that Gil sang. It had a little slower tempo than the single did. That’s the one that ended up being rerecorded, the tempo was upped, I changed the lyrics, and it just took off right out of the gate. Neil Bogart, who was head of Buddah Records, I guess he was shepherding it. Whatever the promotion was, that song really caught on. It just had a catchy melody, and I think people really dug it.

JM: The single and album versions of that song were different. How did that happen?

GL: Neil said, “I think if you change it, if you up the tempo and take out the drug references, this would be a hit.” My feeling originally was, I’m a singer-songwriter, and I don’t want to change my words, or something stupid like that. I was digging my heels in at age 24 or 25. But then I was walking around the house, and I was thinking about it, and I said, well, I could change it to “white sock sport” and take out the drug references, and still sort of keep the cynicism and hypocrisy, the difference between long-hair and short-hair and people are still ripping you off, and things like that. So we went in and we rerecorded it.

Kenny Rogers had produced the album that had the slower version on it, but Neil Bogart hired Kenny Kerner and Richie Wise, who I think had discovered Kiss. I think the band had a different name before it was Kiss. But they had them come to the studio in New York and we recorded it with an up tempo. We were playing on it, but there were different sidemen playing, a drummer and stuff. You know, I think it had a calliope at the end.

And Neil was right. He was a consummate record guy, and when he said do something, I should’ve said, “Whatever you say.” I mean, it wasn’t like a long drawn-out fight where I said, “I refuse to change this” [laughs], I just had to wrap my head around it and just see if I could do something that was still appealing to me. I mean, it still has that line at the end, “More than ever it’s love / No lack of faith undermines it”, which is not something that you’d find in pop lyrics, particularly.

JM: Neil Bogart had a reputation as a colorful figure. What was he like back then?

GL: Honestly, we didn’t really have that much interaction except when it came time to either re-sign a contract or argue about something that they weren’t doing. So it wasn’t like I saw him in full action, like that Scorsese series [Vinyl] that’s all about the music business. I mean, Buddah was a colorful place. We knew the people who were there, but Neil, we didn’t spend that much time…

One time he asked us to play a benefit for special needs kids – his parents were on the board up in Westchester. We said of course we would do, and figured it was pretty good to get brownie points with the boss, too. So we met his parents. They were typical New York Jewish parents. Our dealings with him were fine except for the time when they were claiming that when he reissued the first album, which had the newer cut of “Back When My Hair Was Short”, it counted as a second album, which of course it really didn’t count as a second album. So that was what we were trying to clear up when we had our little bit of head bumping with him. So that’s kind of it.

I wish I had more stories, like things were being thrown at us [laughs], furniture and things. It wasn’t quite that intense, but it was still veiled threats, like “Sign this or I’m going to pull the record, pull the promotion from the record” and stuff like that. That’s how that went.

Of course, I had some information at the time that Neil was thinking of leaving Buddah, and our manager Paul Colby at the time said, “There’s no way Neil would leave Buddah.” And of course, I think right after we had re-signed, he started Casablanca Records, and the first thing he did was The Johnny Carson Years [Here’s Johnny: Magic Moments from The Tonight Show], then it was Donna Summer and he launched the disco craze.

JM: I guess you guys didn’t latch onto the disco craze.

GL: You know, we were still doing, and still do, the kinds of songs that we liked. I mean, unless you’re chasing stuff… And I’m not going to say that people haven’t done really well chasing what’s current or trying to stay current, but really, I was used to writing songs because there was something that I wanted to say, or there were some lyrics that sparked my interest and then the melody came, or there was a melody that sparked my interest and then the lyrics came. As to doing like a Bee Gees thing and suddenly doing Saturday Night Fever – I mean, they were great. Barry Gibb and those brothers were amazing melodicists and stuff. But we weren’t really in that ballpark. If we had more records on the charts, maybe we would’ve evolved into something different. But pretty much we were a folk-rock group, and it wasn’t going to be competing with Donna Summer or anything.

JM: You mentioned Kenny Rogers, who produced your first album. What was it like working with him?

GL: Well, he was great. Obviously, I knew him from The First Edition. I think he’d been in the New Christy Minstrels before that. He was a great guy, and he actually might have played bass on one of the songs. Gil didn’t play bass on that album – they had other people coming in to play bass. And Kenny sang background vocals. He really liked this one song “42nd Street” that I had written.

We recorded it down in Torrance where they had a song that I guess was a big hit on the West Coast called “Chick-a Boom (Don’t Ya Jes’ Love It)” by Daddy Dewdrop. There was a great little studio down there.

Kenny was great. I think he liked the songs we were doing, and he was open to ideas and we were open to ideas that he threw out to us. I know that when we sang “She Made a Man Out of Me”, the first version of it – there was a single version of that also – Kenny had this real high part [sings]. Kenny’s voice is distinctive, so I can always hear that harmony in there. He’s a nice guy. Still a very nice guy.

JM: In the documentary, the song “42nd Street” was highlighted a bit. That was a different era, and you grew up out there. What was the craziest thing you saw or did on 42nd Street back then?

GL: Whoa! Probably taking a picture of our band in the middle of 42nd Street might have been the craziest thing we did. We waited for traffic to subside.

The craziest stuff I saw… That’s a good question. You always were seeing people lounging in hallways, like I say in the song. And there were these subway arcades where you could buy ten 45 singles for like a dollar. I was always looking for things that were written by Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, or Carole King and Gerry Goffin, or Hal David and Burt Bacharach. Or even Randy Newman, if he’d written a song for somebody. I was checking it to see who did the songwriting, and not really who was the singer, because I just knew those songwriters were so great, in my opinion. They were the Brill Building writers.

So those arcades were down in there, and there were bookstores down in there, and these little record stores. For a kid from Westchester, it was kind of an adventure. I mean, obviously I had to keep my eyes open because there were some seedy elements. But 42nd Street was nothing like it is now. It has become a family destination – it’s just crazy. I mean, when I left New York back in the late ’70’s, people were sleeping in Grand Central Station, and now it’s food courts. It’s all changed. Those pictures of the marquees, where you could go see a couple of movies for a dollar or two, or it might’ve been even less, they’re like relics. It was just a whole vibe.

There were some great bookstores around Times Square, too, at the time, little bookstores. I used to collect paperbacks. For me to buy an H.P. Lovecraft book, they were like three dollars or four dollars. That was about the equivalent of eight or twelve paperbacks, because hardcovers were expensive. It was just an adventure to go into those bookstores and look in those record shops, and then going to see a couple of Philippine horror movies with John Ashley. It was great. It was goofy fun, but at the same time you knew that there was heartbreak somewhere, because people were lounging in hallways and there was the whole seedy underbelly of it. There were Tad’s Steaks for $1.29, and spaghetti by the plate, and downstairs drugs were being sold and stuff. I wasn’t a part of it, but I was observing it as a kid.

JM: In the documentary there was a brief mention of the Gold Record that you guys made. Could you fill in the story on that?

GL: Mike Harrison, who was a DJ on WNEW FM, which was the premier FM station in New York City at the time, really liked “42nd Street”, and I think he tied into the lyrics and what I was describing. That was how he found that whole experience, too. So he played the heck out of it. I’d find notes from my mom that said, “10:00 in the morning, Mike Harrison played ’42nd Street'”, then I’d find a note, “at 3:30, Dennis Elsas played ’42nd Street'”. It was weird to hear it on the FM. To hear your song being played on the radio was amazing.

So Steve and I got the idea that it’d be great to give him something to thank him for championing at least that cut from the album on the FM, which was kind of a big deal in those days, to be on FM. So we got one of those singles from Mercury which was just a black vinyl single, and we got some gold spraypaint, and we spraypainted it gold. And we put a little inscription, “Hearing you play ’42nd Street’ on your show is worth a million to us.” We got a cheap frame and we put it in there, and we delivered it down to WNEW in New York. We didn’t think anything more than we were just trying to thank somebody. How else really could you thank them for playing your stuff, which was so great to us?

Then years later – I’m talking about 2014, or maybe right after we recorded the new album; it took us a year or so to mix it back and forth – I googled Mike Harrison to try to find out if he was still a DJ somewhere. Maybe he could play it. What I found out was he was now the publisher of an online publication – it was RadioInfo and TALKERS Magazine, which were the premier online radio trade magazines in the country. I get back this beautiful email from Mike, because I didn’t even know if it was him. I figured it was him, because who else would be involved with radio? But I hadn’t talked to him probably since back in 1971 or ’72. And I got back this beautiful email that said, “It’s so weird that you reached out to me about Gunhill Road, because I was just mentioning the group to my son, who’s now an attorney. I believe things happen for a reason, and I believe in serendipity. I remember that you guys gave me the sprayed gold record, and I was so touched by it. I carried it around with me every time I moved offices or moved to different locations. I carried in around until it literally fell apart” – the cheap frame fell apart – “and I treasure this fake gold record as much as the real ones I got from Fleetwood Mac and Bruce Springsteen later on.” It was just great.

He said, “I would do anything to help you guys.” He did the liner notes for us, he introduced us at The Bitter End [reunion concert]. He just became like the Fifth Beatle. Mike couldn’t have been more complimentary about the songwriting and about the way the group sounded. He loved the album. We’d done 19 tracks, and he said, “Nobody just does this.” It was all on our own power. Nobody was telling us what to do, so we just did the songs that we wanted to do, and how we wanted to do it.

Honestly, I had forgotten totally about the fake Gold Record until he mentioned it in the email. Then, of course it all came rushing back. I forwarded it to Steve, and of course Steve couldn’t believe it either. It was fantastic. It was like having given George Martin a thing of Life Savers or something, and then years later you contact him and he says, “I want to produce your album.” It just blew us away. I said, “God, I hope he likes it when we send him the album,” and of course he did. He’s just been fantastic. He’s a real mensch. He’s just a great guy.

JM: After the music thing tailed off, you had a successful career in the animation industry. Could you give a summary of that part of your life?

GL: What happened was that as the group went through different incarnations… After the hit record then we didn’t have another hit record, we kept trying to get a record deal, and the venues we were playing got smaller and smaller, bass players came and left, and we tried playing with a drummer for a while. Then finally by 1976 it was just Steve and I playing for this college circuit, where people remembered the record. But it just he and I. We would talk to each other over the phone and say, “What are we going to do?”

Now Steve worked for his dad. His dad was a pharmacist who was making additives, kind of industrial products. Steve, when we weren’t playing, would be helping his dad. So Steve sort of had a job to go to. I didn’t. Music was all that I’d really known, as far as doing stuff. To make a long story probably longer, I went out to California to visit a friend, and there I reconnected with Tom Catalano, who had produced for Neil Diamond and Helen Reddy’s “I Am Woman”. He was a pretty big producer. And they had offered me a songwriting contract even before I started playing at The Bitter End, but it was like for $100 a week and I never took it. So that’s another example of something like, what if I had taken that contract and ended up writing a song and Neil Diamond sang it? You could say, what if I had taken that trail? But it’s not like Choose Your Own Adventure. You get one time through, at least unless you have a time machine to go back.

So I went out to visit my friend, and Tom Catalano had a record label called Tomcat, which looked like a fruit label from those cartons of lemons and oranges you get, like a California fruit box. So I played him some songs that I had written over the years, and he said, “Ah, where have you been? These are great.” Blah, blah, blah. So I moved out my stuff out to California, and I didn’t realize that Tom was going through a divorce and that the record label was getting ready to fold. It was being sponsored by RCA, and had been around for a couple of years.

But meanwhile, I moved all my stuff out here, so I needed a job, a regular job to keep the lights on as they say. And through a friend I heard about a job over at Hanna-Barbera. She knew somebody that worked at ABC children’s programming, and they said there might be a job over at Hanna-Barbera. So I went over and met with the person that hired people. He said, “Well, there’s a job opening, but it’s in the stockroom changing water bottles and punching animation paper.” He said, “You’re kind of overqualified for this job”, because I’d graduated from college and everything. So I started punching animation paper and changing water bottles.

Then I started looking at the scripts and reading some of the stories, and eventually I submitted some ideas that got accepted. And then they started an apprentice writing program. There was a Popeye script that I wrote that the woman at CBS really liked called “Spinach Fever”, which was a parody of disco, you know, with Popeye opening his can of spinach… It landed on the turntable of a record player and the needle came over it and opened the can, and then Popeye ate it and in his disco suit beat the hell out of Bluto, who was wearing his white disco suit. It was a parody of Saturday Night Fever – “Spinach Fever”. She really liked that, so I ended up doing 13 Popeyes, then I wrote some half-hour Scooby Doo’s.

And then a show started up about these little characters, these little creatures who were three apples tall and blue called the Smurfs, that came from Belgium. So that started. It was an hour-long show, and I wrote a few episodes for it. And then they expanded it because it was so darn successful to an hour and a half, and they asked me if I would story-edit the last half hour. So that meant 13 half-hour stories. So there was a whole series of books by Peyo, who created the Smurfs. Actually, the Smurfs sprang from these books about Johan and Peewit, who were medieval serfs, you know, they were low on the totem pole guys that helped the knights and stuff, and the the Smurfs were ancillary characters. So I took some of those stories and adapted them, and then from there I never really looked back.

I worked for Hanna-Barbera for probably 20, 25 years. The last things I was doing for them was Scooby Doo on Zombie Island, which became a huge hit and re-launched their whole video department. Then I worked on a second made-for-video Scooby Doo and the Witch’s Ghost. And the last one I did for Scooby was a story for Scooby Doo and the Alien Invaders. So it was great. There were Emmy nominations for Smurfs.

There were Emmy nominations for a Christmas show I wrote based on a poem by a woman from the Midwest. The poem was called “Jeremy Creek”, and we called it “The Town That Santa Forgot”. Dick Van Dyke did the voice, and he came in with a video camera and he was taking pictures of us. And we said, “No, we should be taking pictures of you.” And he was saying, “Well, this really the first animated thing that anybody asked me to do.” I guess maybe Mary Poppins didn’t count as a fully animated thing. But he was nice as could be. And then I got a third Emmy nomination for working on Disney’s Doug, which was almost like a sitcom. It was Porkchop the dog and Doug. It was a pretty big hit for a while. So that became my second career.

And over those years, also, I wrote a couple of horror movies – The Prowler, and one that’s called Too Scared to Scream. Because I love horror movies. It was just great. And regarding songwriting, I would write lyrics into the script, for Scooby on Zombie Island, for Smurfs, and some other specials sometimes. I wouldn’t even bother doing the music because they had people to do the music. So I’d just write the lyrics, and then I would describe the action, and it was great. It was really a fun job.

So I went from one dream job to another dream job, making up stories. I mean, obviously there were deadlines and meetings, things that went on along the way. So it wasn’t always a bed of smurfberries. It was really fun to be a part of something that was so successful, as the Smurfs were. It was just huge. We were pretty good friends with Peyo and his wife and his kids. We would go to Belgium all the time, to Brussels. So it was really fun. Of course, being friends with Scooby and Shaggy, [in character] “Rello”. “Let’s get outta here, Scoob!” That was always fun working with those guys, too, because they were always hungry and scared.

And now I’ve moved to my third career.

JM: I probably saw a lot of your work growing up.

GL: People have said to me, “That was my whole world.” And I said, “Yeah, well I hope you were raised OK [laughs]”. I tried to make the stories funny. I just tried to make them funny to me, and if I thought they were funny and sort of clever, I figured… You know, I always liked Rocky and Bullwinkle while I was as a kid, and even though some of those references maybe I didn’t get, I obviously got enough of them to think they were funny. So I tried to make them work on levels that adults would like, never forgetting the kids. So there were funny sight gags and stuff, too. It was great.

JM: There’s a theory out there that Shaggy was a bit of stoner, which is why he was hungry all the time. Any insights on that?

GL: I’ve heard that so many times. I can tell you that in my experience… Shaggy was kind of modeled on Maynard G. Krebs from The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis. If you look at him closely you can see that was the reference. Yes, they are hungry and scared, but sometimes people are just hungry and scared, not just because they have the munchies. They’re just naturally hungry. These guys are naturally hungry, let’s put it that way. I know that’s gone around for years, but as far as I know, I never saw any evidence of that.

JM: What brought you to Santa Barbara?

GL: Well, we’d been coming up for years from L.A., because a cousin of mine was a doctor, so it was a good excuse to come up and get a check-up, and have a weekend away from the maddening crowds and traffic. Of course, it was always expensive, even back in the day. Santa Barbara was always more expensive than other places.

You know that old saying – you ask somebody, “If you ever find anything, any good deal somewhere let us know”? All of a sudden the phone rang, and a friend of my wife who’s a realtor told us about a place, and I thought maybe it could be something that might be interesting. It really needed a lot of work and stuff like that, so it didn’t look like it was going to happen. But then it did happen, and it was really a fantastic move. I mean, we love L.A., love the ethnic food there. There’s nothing in L.A. that we didn’t like except the traffic. You’re so exhausted by the time you got to a meeting [laughs], you could barely pitch.

But Santa Barbara has really great people who have usually been involved in successful careers elsewhere, although there’s certainly people here that have launched their careers from here. But they’re just interesting people, they’re kind people, they’re charitable people, and they care about the environment, about oil spills and things like that. It’s really a great place. Everything seems to just take minutes to get to. The only drawback was there was no rain – now we’re getting no sun. But it’s just a great place, and we really didn’t know how great it was until we actually spent time here. It’s really a small town, but big enough to have a symphony. Could it have more movie theaters? Yeah, maybe, and more restaurants.

For inspiration, if I’m walking on the beach I’ll get ideas for lyrics, or I’ll be working on story ideas for scripts while the waves are going. We’ve really been blessed to live here. And, of course, people didn’t know about my previous career singing. People will say, “I didn’t know that you wrote songs. I didn’t know that you played.” It was just something that happened back in the way back, the wayback machine. That’s how it all came down.

We used to come back to L.A. on Sunday nights, and I’d say, “Can’t we come back on a Monday? We could leave early.” And then, when my wife retired – she worked at Hanna-Barbera, too [Alison Leopold, who was an ink and paint supervisor for many shows] – I could do my stuff by email and we didn’t really need to go in except for meetings and stuff. It became more of a hassle each time you’d drive in, because people are on their phones, people aren’t paying attention. You’re driving at 80 and all of a sudden the traffic goes to 0. There’s no such thing as slowing down. It goes 80 and then 0, so if you’re on your phone or doing anything besides really concentrating I don’t know how you avoid accordion-ing yourself.

It’s a great town. I love California because at least the sun is warm, and you can wear a T-shirt all year long, you can usually park somewhere and walk. There’s plenty of great places, but this has been a really great place with lots of talented people.

JM: What advice would you give to an aspiring musician?

GL: Wow, that’s a good question. I thought you’d ask about aspiring writers. But for an aspiring musician, it seems like what musicians have to do now is just build up a fanbase by playing a lot. I mean, in the old days the Holy Grail was trying to get a record deal. Once you got a record deal, that was sort of like, “Wow! You’re on record!” Now you can make your own records and put them on YouTube, so now the record companies look at the internet to try to find people.

The advice for all things creative is to be true to what you want to say. A music producer once told me, “Glenn, if you have something to say, say it.” I think that’s kind of true for everything. You have your own kind of vision. Everybody sees the world a little differently. Try to make your stuff unique. And if you believe in your stuff, don’t chase trends. Just do something that feels good to you, that you enjoy doing, and then how much more can you ask for? And if you can make a living out of it, that’s just gravy.

But, honestly, doing horror movies and writing Smurfs and having people come to hear your music, I mean you’d pay people to come listen. The few times when I’ve played with a friend of mine who’s a guitar player in Santa Barbara, I forgot to put the tip jar out. That’s how anxious I was just to start playing for people [laughs]. We’d go the whole night and the tip jar would be gone. So much for being a smart businessman.

But creatively, for music or anything else, just write what’s in your heart, your commentary on the world, or whatever inspires you. You know, try to do something different, or just do something even familiar but just do it really well. And work with people that you like, that you get along with. I think everything else follows from that. It’s probably been said by other people – if you love what you do, then maybe other people will, too. The idea being, if you believe in it and you think it’s something good, then other people will, too.

It is weird to have people come over and say, “Oh, we really enjoyed that.” I don’t know what to say beyond just, “Thank you.” Songwriting’s really so personal, much more so than the writing of Smurfs, because Smurfs was created by somebody else. I was writing for something that already existed. But songwriting is such a personal experience – it’s you and the guitar or piano or whatever in your room, and then you take it out and give it to your bandmates and arrange it. Then it’s out in the public, and you find out if people liked it or hated it, or if it sounded good. It’s like writing a letter. It’s like any kind of writing – it’s very personal.

I always try to encourage students, whether they’re in the elementary schools or over at UCSB, just to be creative. Come up with some interesting twists. Just do what’s fun for you to do, and enjoy what you’re doing. If you’re writing stuff just to make money – I’m not saying people can’t do that and make money or chase a trend or try to copy something – but to me it was always, if you like what you’re working on, whether it’s a script or a song, and you’re enjoying it, then even if you never sell you’ve still got the enjoyment and the time spent being creative.

And I can guarantee you that if you’re in that sweet spot, the time really flies by. I mean, you can sit there to work on something, and two hours, three hours just go by. Whereas sitting around doing anything else, you’re watching the clock drag by. So if you spend your energy on something you like, is it work? It can be work just because you’re trying to do something and make it good. But it’s not work like digging a ditch – unless you really like digging ditches, which is OK, too. It’s really just a matter of inspiration and following your inner voice. I know it sounds really cliche, but just write what you like and what you want to do. Let nature take its course.

JM: Will we have to wait 40 years for the next Gunhill Road album?

GL: I think if we do that it’ll be called “Dust in the Wind”, because we’ll be dust by then. No, I think we’re probably going to go back in and record some more. The idea of showing the documentary and then playing would be a fun way to try to drum up some interest or something.

We’ll record again. Obviously, it’s not like a money-making proposition. I guess you could make a million dollars if you started with two, and then spend a million recording. But now music is sort of given away pretty much free, and money is made by performing live.

But it’s really just being out there and touching people, and putting these songs for whatever posterity is, and having people respond to it. We can’t wait 40 years. I don’t think our vocal cords will allow us to do that. And it’s too much fun to do it. I mean, it’s been six years just to get this thing made. When Eric was doing the documentary, I don’t think he realized how much work it was going to be. I kind of knew, because I know a lot of people who work on documentaries, and how much work it takes to go through the footage and get the story that you want to tell. So from 2011 to recording the album in 2013, then having it mixed by 2014 and playing The Bitter End and then the album came out in 2015, and here it is the beginning of 2017, so you’re talking about six years [laughs] that already went by.

So no, it won’t be 40 years, I can guarantee you that. It’s too much fun working with the guys, and really connecting with people. I think that’s why people do all the stuff that they do anyway creatively – it’s to touch other people. You can’t even put a price on it. It’s really so much fun. It’s great. We’ve all been really lucky to be friends for 50 years and to play together again, which is something we never thought that we would be doing. People really respond to us and to the story.

I was thinking this week that in a way it’s actually better that we were sort of a One Hit Wonder. If we had four hits, it would just be that we had some success and then disappeared. With one hit, it’s almost like we had the door cracked open [laughs], and then it slammed on their fingers. It was just a thing where you just got a taste of it, and then it was gone. So I think it actually works better than if you were like England Dan and John Ford Coley, who had like three or four hit records. But whatever it is, it’s fun, and it’s thrilling for Eric as a first-time director to be experiencing the ride, which is also connected to his family. It’s great for him to see that kind of acceptance. But it’s hard, it’s hard doing documentaries. That stuff is not easy. But like everything else, you learn about stuff as you go.

Discussion

No comments for “Interview: Glenn Leopold”