Saxophonist David Sanborn has seemingly played with everyone: David Bowie, Stevie Wonder, Eric Clapton, Bruce Springsteen, James Taylor, Elton John, Linda Ronstadt, and many, many more.

Sanborn started playing saxophone to strengthen his chest muscles after a childhood bout with polio. His earliest recordings date back to 1967 with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, with whom he performed at a little festival called Woodstock. His profile grew immensely in the 1970’s, when he was the go-to guy for laying down a saxophone solo. In that decade, he also started recording his own albums.

One notable milestone in Sanborn’s career was the 1986 album with keyboardist Bob James called Double Vision. The album spent 63 weeks on the Billboard charts, and won a Grammy for Best Jazz Fusion Performance, Vocal or Instrumental.

This interview was for a preview article for noozhawk.com for the Double Vision Revisited show with Bob James and Marcus Miller, who also played on the Double Vision album, at the Granada Theatre on 8/11/19. It was done by phone on 7/25/19. (Melanie Futorian photo)

Jeff Moehlis: What inspired you to to revisit the Double Vision album with Bob James and Marcus Miller?

David Sanborn: We had actually never done this music live before. We were on a jazz cruise a couple years ago – Bob and Marcus and I were all there together doing separate things, and we decided to have a concert one night where we just played all that music live. We had never performed the music live. We did the album and put it out, and then because of our various schedules we never had a chance to go on the road and play the music live. So when we did it on the cruise a couple years ago, we realized that, wow, this stuff is pretty good, and were lamenting the fact that we had never done any shows. So we said, “Let’s try to get it together.” It took us about a year and a half to work it out with everybody’s schedules, because everybody’s working a lot individually. We came together, and now we’re going to do it. It’s pretty much that simple.

JM: Were you surprised at how successful that album was?

DS: Oh, completely. All of us were completely floored by the fact that it was so successful. We never expected it. In retrospect it was kind of odd that we never went out to, in a way, capitalize on it, or just to honor the fact that we had made this record that had reached so many people. We missed the opportunity to do it while the record was still current. But, better late than never, right?

JM: Exactly. I know that you had worked with Marcus before that record, but was the Double Vision album the first time you had worked with Bob?

DS: I played on some of his records that he did for CTI, and I think some of the early stuff that he did for Columbia. I’m not sure of the timing and all that, but I’m sure that we had crossed paths before that. But we had never actually kind of played in the same room together. I mean, we might’ve been thrown together in a couple of oddball situations here and there. I remember I did something at the Grammys one year with him and George Benson and George Duke… I can’t even remember what that was [laughs], sometime in the mid-80’s. But aside from that, we’d never really done anything together.

Then Bob and I did an album together, a duo album four or five years ago, and we talked then about the fact, once again, that we’d never done that music live until we did it on the ship, and here we are out there doing it.

JM: Are you willing to go on record on what your favorite Bob James composition is?

DS: Oh gosh, there’s so many of them. I mean, I love all of the stuff that we did on Double Vision, and honestly I don’t remember which ones were Marcus’ and which ones were Bob’s. You know, having done a record and tour with Bob, there’s so many of his songs that I enjoy playing from that record – it’s called Quartette Humaine. That was a great record for me to do, and then consequently we played the music live. But I’d be hard pressed to pick a favorite Bob James tune.

JM: I have to ask because the 50th anniversary is coming up. You played at Woodstock – what are your memories of that?

DS: Wet. A mess. It wasn’t that out of character from a whole lot of other festivals that were going on at the same time. It just happened to be bigger and a little messier, and somehow it captured the zeitgeist of the world. It was a moment in time when everything seemed to come together. I think the fact that there was thirty to forty percent more people than had ever been at a music festival before, and there was no real violence, and it was relatively peaceful in the face of some difficult circumstances – you know, the rain, the mud, and the fact that there was no security.

It was kind of the apex of the ’60’s. It was 1969, right? It was in so many ways the end of the ’60’s. I think it became very clear to corporate America that “Hey, this is something here. It’s something we can make a little money with.” Not that they weren’t aware of it before, in the mid-’60’s, but it just became clear that this was more than just a little section of the economy [laughs] as it were. This youth movement thing was something that they could really capitalize on, and in a way it kind of put the nail in the coffin of any kind of idealism.

Then we got into the ’70’s, and things were a little darker, you know? It was kind of the end of an era, in a way. And it was a great moment. All these great musicians were there, all this great music happened. I came up in the ’60’s, so for me it wasn’t this great moment, it was just kind of the evolution of things to that point. I don’t know, it’s very hard to talk about what that represented, if anything. I mean, I certainly didn’t think about it at the time. It just seemed like one more festival, and all of a sudden it’s like ca-ching, trademark [laughs]. It was thrilling and depressing, in equal measure.

JM: I think it was Arlo Guthrie who said about Woodstock, “I’m told I had a good time.”

DS: Yeah, that’s pretty much it. That was definitely a big part of it, but it wasn’t all of it. I mean, the drugs were there, but they hadn’t completely overwhelmed the movement and the idealism. But it was getting there, and then the ’70’s hit. The death of that, to me, was quaaludes [laughs]. Then we moved into the quaalude ’70’s. Oh boy, here we go. We’re not enlightened, we’re just sedated [laughs].

JM: Speaking of the ’70’s, you hit some high points in the ’70’s. It wasn’t all quaaludes, right?

DS: Yeah, right. You know, I had a very good run of things in the ’70’s and the ’80’s, and even into the ’90’s. I have no complaints. You know, the fact that I’m just able to make music after all these years, that I can continue to do something that I’ve done professionally for 55 years, that’s kind of remarkable to me. That I actually do this. I never really had a straight job. The last straight job I had, I think, was I worked on an ice cream truck for a day when I was in high school.

JM: I want to ask you about a few people that you worked with, one being Stevie Wonder. What was that experience like, touring and recording with him?

DS: I loved playing with Stevie. He was one of the most creative people I’d ever played with. I mean, he would write a song every day. We would go to soundcheck, and he would have a new song for us. It was either a complete song or the beginnings of another song. I remember “Superstition”, he was evolving that song. “Tuesday Heartbreak” and “You Are the Sunshine of my Life” and all that, and then “You and I” – those were all ideas that he came up with in his hotel room the night before, and then he kind of workshopped it with us at soundcheck. It was an extraordinarily creative atmosphere to be in. And to be on the stage with somebody who consistently, night after night killed it… That’s pretty much all I can say about Stevie.

JM: Another one who I know everyone asks you about is David Bowie, and like a lot of people I love the work you did on “Young Americans”. How did you get that gig with David, and what was it like working with him?

DS: My friend Michael Kamen was asked to be the musical director for Bowie when he did the Diamond Dogs tour in ’74. Michael knew me, and he knew that Bowie was looking for a saxophone player, so he called me and I did that tour and Bowie liked the way I played. Then we to Philly to do the Young Americans album, and he asked me to join in on that which I did, and then I did a tour with him for that record. And it was great. It was one of the high points of my life, working with him.

Once again, he was an extraordinarily creative person. He’s somebody that never stopped working, and I think that’s the thing that strikes me about a lot of people I worked with – James Taylor, Rickie Lee Jones. These people are hard-working people. They work at what they do. Of course they’re extraordinarily talented, but they don’t rest on their laurels, they don’t take it for granted. They’re always working. I’ve been lucky to be around that kind of creative energy in my life. It’s been inspirational to me.

JM: I talked to Mike Garson recently about that time with David, who he called the “ultimate casting director”.

DS: Oh yeah, I think so. I think he was great. He was creative on so many levels, as a conceiver of how to stage music, and an extraordinarily creative musician. He was an artist. He was a true artist. An artist in the true sense of the word.

JM: I also want to ask about Todd Rundgren. What do you remember about recording with him on A Wizard, A True Star?

DS: I don’t remember much about that. I was living in New York at the time, and he had a studio there, and I just remember Randy Brecker and I went in very late at night and worked with him. I had known him from Woodstock, when both of us were living up there. He was very active as a producer, and I think he engineered one of The Band’s records, Stage Fright. He was just up there working with different people, and I knew him socially, and then I had a chance to work with him. He asked me to do that thing on A Wizard, A True Star. But my work with him was not extensive.

JM: There have been so many artists that you’ve worked with. Are there any that really stick out to you, that are kind of a “pinch me moment” because they were so exciting to get to work with?

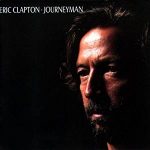

DS: Not really. I guess Eric Clapton was great to work with. He and I were very close for a while. We were on the road together in a couple of situations, and I recorded with him and he played on my record. But there’s so many extraordinary musicians out there, some of them famous and some of them not. So not all of the moments were with people who were well-known. There were a lot of wonderful experiences with people who were kind of below the radar. So it’s hard to say, really.

JM: What advice would you give an aspiring musician?

DS: Well, you’d better believe in what you’re doing, because you’re going to go through some rough times. But if you have a passion for music, and for making music, that’s what will sustain you through the hard times. Because it’s not easy, especially these days. And I guess to me, it’s about being in music for the right reason, which is because you have to do it, not necessarily because it’s a good career path.

JM: You’re doing the Double Vision Revisited tour – anything else in the works that you’d like to mention?

DS: I used to do a television show called Night Music back in the ’90’s. I started out thinking that was such a great experience to do that show, why don’t I try to do some version of that now on whatever distribution formats seem to be the most appropriate. So I started out with that idea, of just playing music in an informal circumstance or setting with people I admired, friends of mine, people that I always wanted to play with or new artists that I wanted to played with. So I started doing this thing called Sanborn Sessions, and we recorded I think seven or eight shows at my house – I have a home studio in New York. It’s kind of fly-on-the-wall stuff. I had Michael McDonald and a great gospel singer called Brian Owens on, I had Kandace Springs, a really great singer/songwriter, Jonatha Brooke, another singer/songwriter, Cyrille Aimee, a great jazz singer, and Terrace Martin, who’s a hip-hop producer and saxophonist. We’re going to distribute it across difference social media formats – Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, whatever seems appropriate. We’re going to start that in the fall.

Discussion

No comments for “Interview: David Sanborn”