Bruce Sudano has had a varied and interesting musical career, from co-writing the song “Ball of Fire” with Tommy James, to recording James’ song “Tighter, Tighter” with Alive N Kickin’, to co-founding Brooklyn Dreams and recording the song “Music, Harmony and Rhythm”, to marrying and managing and co-writing with Donna Summer including the hit “Bad Girls”, to writing “Starting Over Again” which was a hit for Dolly Parton and “Tell Me I’m Not Dreamin’ (Too Good to Be True)” which was recorded by Jermaine and Michael Jackson, to a recent active solo career.

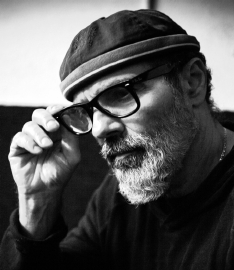

This interview was for a preview article for noozhawk.com for Sudano’s performance at the Libbey Bowl in Ojai, California on 9/4/16, as the opening act for The Zombies. It was done by phone on 8/22/16. (Darren Lau photo)

Jeff Moehlis: Were you a fan of The Zombies back in the day?

Bruce Sudano: Without a doubt. As a teenager growing up in Brooklyn, my first band did a cover of “She’s Not There” and “Tell Her No”. Then later on with Argent, “Hold Your Head Up” was a big favorite. So yeah, they were definitely part of the equation in my early formative rock-and-roll-band Brooklyn basement-rehearsal saga [laughs].

JM: What can people look forward to for your performance at the upcoming show?

BS: I basically do 30 minutes. I do it as a duo – it’s an acoustic duo – which on the surface when I say that it may not seem like it’s a good fit with a rock ‘n’ roll band like The Zombies, but I’ve done numerous shows with them over the last year and a half, and it actually works really well. My set is topical, in that I tell stories – my songs are stories. I do a combination of some new songs that I haven’t recorded yet, which are kind of politically topical, and then I do a couple of songs from my last couple of albums, that are emotionally charged, based on the saga that I went through with my wife. And then I do a couple of older songs from the catalog, songs that were recorded by other artists that I had success with. It’s kind of like that.

I have a little bit of edge [laughs]. Even though it’s an acoustic thing, I have a little bit of a soulful and rock ‘n’ roll edge to my deal. It works really well with The Zombies. It’s actually quite complementary.

JM: If you don’t mind going way back, can you tell me about your association with Tommy James?

BS: I had a band called Alive N Kickin’, and all through high school and college Alive N Kickin’ was one of the top club bands in the New York area. We were the house band at the club in Manhattan called The Cheetah, which was on 52nd Street and 8th Avenue. Tommy’s apartment was on 8th Avenue and 54th Street, and somehow through our manager he came down to see the band. I was an aspiring songwriter. I was a teenager who wanted to be a songwriter. So I met Tommy.

On breaks in between sets of me working at the club, I would go over to Tommy’s apartment and try to write songs with him. I was very naive as a songwriter, and Tommy was at the top of his game right then. He was one of the top Pop Stars of the moment.

I co-wrote a song with him that was pretty much a hit for him in 1969, called “Ball of Fire”. My story is that the song was called “Ball of Fire”, and my contribution to the songwriting was “of”. I sat there and tried to help out, but basically Tommy constructed the song. You know, then he brought me into the studio and I sang backgrounds on some songs. I would just watch him work, and watch him make a record.

In those days, as a young person, you couldn’t get into a recording studio. It was very difficult – they were expensive, they were booked. It wasn’t like today where you are able to record in many different ways. Getting into a recording studio in those days was a dream. So basically he mentored me, and then wrote a song and produced my band, and we had a hit with “Tighter, Tighter”. I’m forever indebted to Tommy. He brought me up under his wing and I learned a lot from him. I got my first record deal with Roulette Records with Morris Levy because of Tommy. That was a whole other learning experience.

JM: Speaking of Morris Levy, he was somewhat notorious, shall we say? Did you have any crazy interactions with him? I guess you were pretty young…

BS: Well, because I was so young… I mean, here I was, I was this little skinny kid with hair down to my shoulders. We ended up having a big hit song and we weren’t getting any royalties. Basically I would go up to Roulette Records every other week and go see Morris, and say, “Morris, this song is Number 40. How come I don’t have any money?” He’d go, “Aagh,” and he basically would write me a check for $1500, and sent me on my way.

Meanwhile, everybody else at the company, and anybody who knew anything, would be like, “I can’t believe this kid is going up into his office and asking him for money, and actually getting it.” But I was just so naive, that I didn’t know any better. I didn’t care. Because I didn’t know, I didn’t care.

Morris, for all his notoriousness, and he was such a character, was also a great guy, and a father. There’s always a duality that goes on with those kind of people. Growing up in Brooklyn in those days, many of the clubs that we played in were run by what might be called questionable characters. But they were lovable, crazy guys. I was kind of brought up of the school of be aware of these people, but don’t get involved. So I always kept my distance, but they always viewed me as the quirky little artist kid who didn’t know any better. And I think that’s how Morris viewed me. I guess he just said, “Alright, here’s fifteen hundred bucks. Just go away you little kid.”

JM: He probably owed you more than that.

BS: Oh, yeah, he definitely owed me a lot more than that, for sure. It’s not like I was getting what I deserved, but at least I got something.

JM: Are you aware that some people find parallels between the song “Ball of Fire” and what happened on September 11th? Obviously it’s a coincidence.

BS: I think I am aware of it. I mean, I remember somebody bringing it to my attention a couple of years ago. Kind of odd, but it obviously is a coincidence. But we can get into the whole concept of prophecy in the spirit, and who knows how all things work. But we can just view it as a coincidence because more than likely that’s all that it is.

JM: Later on you were part of the band Brooklyn Dreams, and you guys had a hit with “Music, Harmony, and Rhythm” and ended up on Casablanca Records and all that. Can you give a nutshell of what was going on with that band, and how that played out?

BS: I had been to L.A. numerous times, back and forth from New York, and then finally in ’76 moved to L.A. Joe [“Bean” Esposito] and Eddie [Hokenson] were guys that I knew from the neighborhood – we had played in bands in the neighborhood together – and the three of us founds ourselves out here. We ended up putting a group together. We were all pursuing solo things, and it would be easier if we put something together as a trio.

We got signed to Millennium Records in New York. We gave up our apartments out here in L.A. because we were going back to New York to record, and then they said, “No, there’s been a change. You’re going to record in Los Angeles.” We had no place to live. We moved in with our friend Susan Munao, who was another friend from Brooklyn, who was the V.P. of press at Casablanca Records. I called her up, and I said, “Susan, we have no place to live. Can we come and stay with you for a few days until we can get new apartments here in L.A.?” She said, “Sure”. We were sleeping on the floor in the living room, and one Sunday afternoon Donna [Summer] came over to visit her press person. That’s how I met Donna.

You know, Brooklyn Dreams recorded its first record. “Music, Harmony and Rhythm” happened. Donna came and sang background on our song called “Old Fashioned Girl”. Then subsequently what happened was that Millennium sold our contract to Casablanca. We basically had no control over that. I think it was kind of a power move by Casablanca, because at this point now I had a relationship with Donna. They were trying to keep Donna under control, in a way. So then we found ourselves on Casablanca and went from an R&B kind of group, and got put into the disco world [laughs]. That’s a little bit of the Brooklyn Dreams story. There was “Heaven Knows” with Donna, co-writing “Bad Girls” and numerous other songs.

JM: Speaking of “Bad Girls”, of course that was one of Donna’s huge hits. How did that song come together? What was the process like?

BS: We were having these conversations with Donna. Casablanca Records was on Sunset Boulevard, and across the street there was this place that I think still exists – there were lots of call girls walking up and down the strip right about there. Donna and a couple of the other black girls, and even the white girls, that were working at Casablanca would go across the street to call us a trolley and they would get confused with the call girls that were working at the place next door.

So Donna had this thing in her mind, and she wanted to write a song about it. There was another friend from Brooklyn who had a studio called Magic Wand in Burbank, and when he had downtime we would go to the studio and set up mikes and just vibe on things. Someone would have an idea, we’d set up some vocal mikes. Joe and I would be on acoustic guitar, and Eddie would be playing a percussion instrument, Donna would be on a mike, or I’d be on piano, depending on what we were doing. And we would just jam. “Bad Girls” came out of one of those jams, and that’s how it happened. Just like that.

JM: A lot of the songs that Donna was recording in the studio around that time, including “Bad Girls”, were with Giorgio Moroder. What was it like working with him?

BS: Giorgio was easy. He was very good at translating the songs. He had great people – a great engineer, and great arranger. He work with Harold Faltermeyer on the “Bad Girls” record, and Harold did most of the arrangements. Jurgen Koppers was the engineer, and got great sounds, and Keith Forsey was the drummer. So it was a combination of Giorgio’s ears and working with talented people who filled out their roles really well.

JM: Not too long after “Bad Girls” came out, there was the big Disco Demolition Night in Chicago. Did that have any noticeable effect on what was going on with you and Donna?

BS: I don’t know if it had an effect on what was going on, or if it reflected what was going on. But there was definitely a backlash that was taking place, I think that we were already aware of. Because even on the Bad Girls record, “Bad Girls” is more of a rock / R&B song even than a disco song, and “Hot Stuff” was more a rock ‘n’ roll song than a disco song. So I think that Donna was already consciously transitioning out of what was typically disco, already at that point. And certainly The Wanderer record album that followed that was certainly even more of an evolution away from that. So stylistically, we were already really aware of a backlash, so we were already transitioning out of it. So I don’t know if that thing in Chicago was a reflection of what was already part of the consiousness, which I would think that it was, as opposed to it driving the consiousness.

JM: Casablanca Records has quite a reputation as a crazy place. Was it really as crazy as the stories we hear?

BS: Well, I mean, yes it was. But in context – it was a very vibrant, alive culture. The craziness that went on was just also a part of what was going on in the culture, in general. So the craziness at Casablanca, I think, sometimes that story overshadows the amount of creativity on all levels that were happening there, in terms of the album art, and the music that was being made. It was really a very creative, alive place. You know, yeah, there was craziness for sure going on, but the craziness was going on in the culture. What was going on at Casablanca was just reflecting what was happening in the culture at large.

But the story is that Neil Bogart was a visionary kind of guy, and Donna was an amazing artist and an amazing songwriter, Giorgio was an amazing talent, and there was just a lot of creativity going on there in the moment. Casablanca was a great place. It was really alive and there were a lot of creative people working there.

JM: I understand that there’s a musical in the works about Donna. Can you tell us a little bit about that, and what the status is?

BS: The status is that we just completed a six-week workshop, as step one, just to see where we are with the script. Now we’re making some adjustments. We’re looking to be on Broadway in the not-too-distant future. Too soon to say exactly when, but we’re working, and it’s going to be amazing.

JM: It sounds like it’ll be cool!

BS: It’s going to be amazing. That much I already know.

JM: You also wrote the song “Starting Over Again”, which ended up being a hit for Dolly Parton. What’s the story behind that?

BS: It was a song that I was writing about the divorce of my parents. I was basically 29 years old, and my parents were getting divorced. Regardless of my age it still affected me, and I was writing the song. One day Donna said, “You know, I’m going to sing that song on the Johnny Carson Show. Maybe if I sing the song your parents will stay together.” I was like, “There’s no way that’s going to happen.” She said, “Well, I’m going to do it.” So she went on the Johnny Carson show, sang the song, and the next day Dolly Parton’s people called asking about the song. Dolly recorded the song, and that’s how it happened.

JM: Did it work to keep your parents together?

BS: No, it didn’t. I kind of realized that, and that’s why I said, “C’mon Honey, there’s no way that that’s going to happen.” But she was always positive and optimistic.

JM: What advice would you give to an aspiring musician?

BS: The advice that I always give is be true to yourself. There’s a part of your artistry where you have to glean from other people, but at the end of the day you have to be your own muse, and be your own person, and not follow the trend. If you are part of what’s happening now, fine, and that’s truly what you are, fine. But ultimately as an artist you have to be true to yourself, and not be swayed by what is currently in vogue. I think the biggest mistake artists make is chasing it. You know, that’s not what you want to do. You don’t want to chase, you want to lead, and you can only lead by being true to who you are.

JM: I have a friend who knew Richard Adelman, who played with Donna.

BS: I knew Richie well.

JM: What was he like?

BS: I don’t have any specific stories, other than to speak about who he was as a man and a drummer. He was a sweetheart of a guy. Very sensitive and intuitive and funny, and easy to be around. And at the same time he was an excellent drummer. He would lock down in the pocket, and drove the band in a very consistent, steadfast kind of way. Even after his accident, he remained a sweetheart of a person. He never became bitter, and he was a gentleman until the day he died.

JM: You were part of the American Hot Wax movie, back in the day. That had such an amazing cast, including some people from the heyday of early rock ‘n’ roll. Any memories of that experience that you’re willing to share?

BS: It was a great experience. It was three months of our lives where we were basically all on the set every day. That’s not to say that Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee were on the set every day, because they weren’t. But the other cast of characters…

I became lifelong friends with Kenny Vance, lifelong friends with Brenda Russell, lifelong friends with Jay Leno. It was just a great time. Floyd Mutrux, the director – I stayed in contact with him. In fact, I know that he has a musical called “Heartbreak Hotel” that’s running in Pasadena right now, that I’m planning on going to see. I just went to see The Color Purple on Broadway because Brenda wrote the music for that. We’ve remained friends. So it was a great experience, so much fun. Richard Perry. I mean, it was just a great time.

And for us, for Joe, Eddie, and myself… My first influences as an eight and nine year old into music was my parents taking me to the Brooklyn Fox. Joe Esposito, the singer for the Brooklyn Dreams, his step-father was the the stage manager at the Brooklyn Fox. So for us to be able to be a part of that film was really like coming full-circle, and it really meant a lot to us. To me, it was a great movie. I think it captured the essence of that time, of that moment, very well. It was a very influential time in the music world, those shows that happened back in those days. It was a special time.

Discussion

No comments for “Interview: Bruce Sudano”