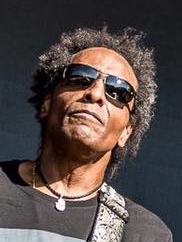

If you’ve heard Bob Marley’s music, then you’ve almost certainly also heard Al Anderson on guitar. That’s him on “No Woman, No Cry” (both the live and studio versions), and many other Bob Marley classics.

Anderson joined up with Marley for the breakthrough 1974 Natty Dread album, contributing guitar with a bit more of a rock feel than was common at the time in reggae. He also played on the Live!, Rastaman Vibration, Babylon by Bus, Survival, and Uprising albums, and was an integral part of Marley’s band for five major tours. Anderson also recorded and performed with the legendary Peter Tosh, including on his first solo albums Legalize It and Equal Rights.

For the last ten years, Anderson has kept the music alive with The Original Wailers. This interview was for a preview article for noozhawk.com for a concert by The Original Wailers on 9/7/18 at Discovery Ventura. It was done by phone on 8/9/18.

Jeff Moehlis: What can people look forward to at the upcoming show?

Al Anderson: It’s going to be like a church sermon with a lot of music, and a lot of singing along and response from the stage to the audience. We have a great relationship with our audience. It seems that they know most of the songs, so we give the opportunity to sing along with us as much as we possibly can.

JM: Your involvement with Bob Marley started with my favorite Bob Marley album, Natty Dread. How did you get that gig, and what were those early recording sessions like?

AA: I was with Paul Kossoff, the lead guitarist of Free, and Island Records had called him to overdub some guitar parts on the Natty Dread album. But his health wasn’t really great, and Free wasn’t touring at the time because of that. He was integral part of the band – his guitar sound was everything. He did the song “All Right Now”. He also had a great touch. He was a great player. So Island Records CEO Chris Blackwell called him to do the session for the Natty Dread album, and he wasn’t in good health. They sent a taxi for me, and I was a substitute for him. Bob was pleased with my production with him, and asked me to join the band.

JM: Did you get a lot of guidance from Bob on what to play, or did he give you a lot of freedom?

AA: No, he just said, “Let me hear what you have.” I was playing a lot of jazz-rock stuff that was maybe a little too fast, and a little too busy in the early stages of the recording. So he didn’t really like that, although they recorded it. But they didn’t keep it. And then he goes, “Play some blues.” So I said, “No problem.” I did “No Woman, No Cry” – that was the first part he really liked, because that was almost like a two-take, one-take song. He really liked that, so he said, “Give me more of that.” I didn’t know what direction he wanted to go in, and at that time he didn’t know me and I didn’t know him. So we were trying to figure out where to take it, and we landed with what was recorded.

JM: Did you experience any culture shock when you started hanging out with him and the rest of the band, being an American coming into a band of people from Jamaica?

AA: Major, major, major, major. It took me a year to learn the language, because you know they speak Patois, and it was very difficult to understand it. They speak fast, and it’s slang. It took a long time to understand what was happening. Basically, I was just trying to get in where I was fitting in to the program with him.

I spent a lot of time with him and his mother in Delaware before I went to Jamaica. I came from England with him to Delaware, where his mother was living with his two half-brothers. We stayed there for quite some time, to get it together to get to Jamaica, to wait for the release of the Natty Dread album. I lived together with his family – his mother and half-brothers – and it was just a wonderful thing. His mother treated me like a long-lost child. It was great. She fed me. She was just a wonderful lady, Mrs. Booker. She’s an inspiration to my livelihood.

JM: Can you tell me about the concerts that were recorded for the Live! album that come out in 1975? At the time, did you realize that something really special was going on?

AA: We didn’t even know we were being recorded. The management and the record company, Island Records, wanted everything to be a surprise. I could never figure out why you would never tell a group of musicians who was being recorded that they’re being recorded. And at that same time I realized that it was the greed from the company, or that somebody was greedy. It possibly could be management, but I think it was more on the recording/distribution. If they recorded us without our acknowledgment, they could do whatever they wanted to do with the image and the sound without your involvement, and then pay you less of what you should normally deserve from a royalty.

What people don’t know is that Bob Marley & The Wailers’ musicians did not get royalties for the live albums that were recorded, and for a lot of material. He paid us a yearly royalty for our involvement, but we didn’t get royalties for the individual and the live recordings, which made a huge success for the company and the management and Tuff Gong Records. That’s what a lot of people aren’t familiar with. They think that the money was equally distributed.

You have to understand that Jamaica did not have an upright performing rights society for musicians, where they looked after publishing, record royalties, and your images. That didn’t exist in Jamaica. There was a lawyer in France who won a landmark lawsuit against Universal, because television and radio was taking advantage of all of the songs being played without giving Jimmy Cliff, Robbie and Sly, Steel Pulse, Third World, The Wailers, Bob Marley & The Wailers – they weren’t giving us our royalty that we deserved from the European Society, and from ASCAP and BMI either.

JM: It’s amazing what record companies have gotten away with, and maybe even nowadays are still getting away with.

AA: They are, but not as bad as it was in the 70’s and into the early-80’s. Because there’s a lawyer from France named Andre Bertrand who won a landmark case, into the millions of Euros for all the artists that wrote and produced music in Jamaica. He made all the European companies pay the recording artists what they rightfully deserved, which was a landmark lawsuit.

JM: Could you tell us about the sessions for the Uprising album, which was unfortunately Bob’s last studio album?

AA: We basically were a tag team. We didn’t sleep for maybe a couple months, and all we did was wait for our turn to either produce or record. It was all-in. “We’ve got to do this record”, so we all jumped into the river, and we all swam ashore at the same time. It all happened. We were like a school of fish. At that time, in terms of recording and producing, we were at the top of our game.

When Natty Dread was happening, he had just left Peter [Tosh] and Bunny [Wailer], and he was making a decision on his career, where he was going to go as a solo artist, and how many musicians, and how his production was going to be, and who was going to manage things. He was putting all the pieces to make the puzzle correct for himself, because it was his first opportunity to think on his own without the other two members – Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer.

JM: Speaking of Peter Tosh, you recorded and performed with him, also. Was there a difference between Bob’s approach and Peter’s approach to music?

AA: Peter was Malcolm X, and Bob was Martin Luther King. Totally different people. Same doctrine, same philosophy, but individually just completely different how they produced their music and how the songwriting came to the bandmembers.

JM: In what sense?

AA: With Peter, we would rehearse the song, and then eventually have a broad idea of what exactly he wanted. We would go in and then improvise with Robbie and Sly, and just knock it out. Bob would write the songs, pretty much on his own, and then he brought the song into the studio and the band would produce the music for him. Peter was more of an inside producer along with Robbie and Sly, with the members. Bob was more like bringing the song into the studio that he had written, and the band would produce and improvise on everything, and even add in. It was an all-around production. It was similar, but it was really different how Peter and Bob orchestrated the music they wanted to record.

JM: How would you describe the Bob Marley that you knew?

AA: He was like running the country. He was like the Prime Minister of Rastafari for Jamaica. He sacrificed his life for his family, his friends, and the country. He was a leader.

Peter was more of a lone wolf, and Bunny also. But they had a large contribution, too. If you didn’t understand or couldn’t read politics in the news, these guys would give it to you in a song where you’d completely comprehend what was going on with the government. “Roadblock”, “Legalize It” – these are political statements. You know, “Legalize it and I’ll advertise it.” Then Bob was “Roadblock” – “I’ve got to throw away my herb stock, be careful for the police on the road”. It was information being passed over to music, so that people on the island could understand what was happening in the government. They were like messengers.

I grew up in America and worked with Motown people, and was familiar with The Beach Boys and Ed Sullivan and Elvis and The Beatles and Chuck Berry, but Jamaica has a whole other way of looking at music, and how they produce and arrange and distribute their music. It’s completely different. It’s not as advanced, and never was, as in America. It’s very complicated when it comes to financing reproduction and distribution in Jamaica. I don’t know whether it was because of the colonial system, or it’s just that the artist wasn’t entitled to a royalty of what he was responsible for creating. And greed, the old greed theory of take as much as you can. Which was a sad part of a lot of the amazing music that came and is still coming out of Jamaica still.

The performing rights society has to look after these artists’ royalties, to be paid to the artists and contribute to the people who produced, arranged, and directed anything having to do with the creation of whatever song that was made and put out to the market. That’s the fair way of looking at it. You would never go to Wall Street and just all of a sudden start taking people’s money. We want Jamaica to be like Wall Street, and equally distribute through the record company to the artist, to the musician, to the directors, to the ghostwriters, to the songwriters, and get their fair share also.

JM: One curiosity in your bio is that I read that you played in an early version of Aerosmith. What’s the story behind that?

AA: I never played with Aerosmith. I used to help them lift their equipment on the road. I would get into all the shows, and Joe [Perry] and Steve [Tyler] would throw some cash at me for food, and I would crash on the floor up on Mass Ave. when they were living in Boston. I was touring with them pretty much as a friend and a roadie. I sold guitars to Brad [Whitford] and Joe. Joe always wanted a Les Paul Junior Custom, or a Standard. I used to get them in New York pretty cheap in the ’70’s, and bring them up to him. And he’d buy every single one of them. They were just great friends, and they used to look after me. I didn’t have a job.

Then I ended up working in Dorothy Muriel’s bakery. It was fantastic between being with Aerosmith and working for Dorothy Muriel. I had enough to get an apartment and a car in Boston. I left Boston and I had met Traffic and Chris Blackwell, and they invited me to come over and do some recording. I worked with Richard Branson first. He was the first CEO who gave me an opportunity to make some money and get me a royalty. He treated me very well. He’s a great guy. Very clever, very smart, very cavalier. He was the first guy who was talking about cellphones and cell communication. He was going to get an airline and a train, get involved in the railway. Just an amazing visionary, which he still is today.

JM: He actually did those things, too.

AA: Yeah, he was amazing. Chris Blackwell was the same. He had a different route that he took. Chris was more interested in building an empire out of the music that the artists were creating on behalf of his distribution.

JM: What advice would you give to an aspiring musician?

AA: Definitely, most definitely, get a great teacher that shows them the theory of how to make music, one, and two, the theory of how after I make music and create music, how I’m going to be a recipient of what I have distributed on behalf of my name and my association. Then you’ll last a long time, and keep a long-lasting relationship with all of your members and friends and whoever’s involved with what you’re doing, what you’re creating.

It’s all about the creation aspect. The guy who writes the song and has his name as the songwriter, it doesn’t mean that he produced the quality of what was distributed. The Wailers were the producers of Bob Marley’s music. He was an amazing, incredible songwriter. Not a great producer. He wasn’t so tech-savvy with mixing and so on. He knew what he wanted to hear, he knew what he liked, and he knew what he didn’t like, and that worked. It worked one hundred percent for him. But in terms of how Bob Marley and The Wailers was produced, it wasn’t Bob Marley who produced all the music and wrote all his music. It was a big collaboration with production and songwriting, which a lot of people aren’t familiar with. And that doesn’t take away from the amazing, incredible poetry and songwriting Bob revealed to us. The real deal about it was that the band produced most of the music that came out of the Tuff Gong studio, everything that was produced live.

JM: And I would guess that if he was still around, he would admit that, too.

AA: Absolutely. He was straight. It’s just that during that time music hadn’t evolved in Jamaica. It was just evolving. It was just coming to a turning point of “Oh my God, this guy has 130,000 people in the arena.” He was doing 180,000 people in New Zealand and Australia. He was becoming this huge box office sell. It was just turning around, and then it all disappeared really fast.

I believe if he was alive today he’d be one of the top draws of all these artists. Without a doubt. I mean, U2 went from playing for a couple hundred people to a couple hundred thousand people. And it took a long time and a lot of hard work, which I give Bono and the guys credit for. But they were able to achieve their agenda because they had the longevity. Bob, he only got a few years. Wow. He passed very early – 36 years old. It’s just not fair.

JM: I know that Bob Marley played a concert at the Santa Barbara Bowl. Were you a part of his band at that time?

AA: Yes, I was. We came from Australia – we were exhausted – and it just turned out to be an amazing day. The recording is really great. The Harvard show – the Amandala show – was great, too. Those two shows are forever going to live with me, you know, inside of me for my participation.

JM: Bands that play at the Santa Barbara Bowl often say that they’re excited to play somewhere that Bob Marley played.

AA: Yeah. We had a huge group. We had horns, percussion, I think we had three engineers, two side engineers, stage engineers, Carl Peterson. These dates, the sound and the band was more and more powerful. When I joined Bob, it was a five-piece band that toured, and Tyrone Downie and myself sang back-up. The I Threes were nursing their newborn children. So it was a five-piece band. It was Bob, Carly [Carlton Barrett], Family Man [Aston Barrett], Tyrone, and myself. We toured Canada – it was 1975, I believe. It was amazing. This was part of my early involvement, and I was amazed how much sound was coming out of five musicians.

And we have a five-piece group today that I’m very satisfied with. We’ll be touring with Chet Samuel on vocals, Omar Lopez on bass, Noel Akein on keyboards, and Paapa Nyarkoh on drums.

JM: Is there anything in the works, perhaps some new recordings?

AA: We have Ineffable Music Group, which is an amazing management company, and we have Paradigm, who are doing an amazing job at keeping us on the road. The Original Wailers didn’t really have that going for us when we started in 2008. Now it’s 2018, and things are really starting to happen.

We’re in the studio producing a new album, which has kind of a Jamaican reggae feel, and we’re going to record 20 songs. It’ll be 20 songs, and instead of doing an LP, it’ll be EPs of five or six songs, so we can put out something every six to eight months, and keep everything fresh. Better EPs. If you’ve got 15 songs on a record, you’re not going to listen to every song. I going to go, “Oh, this is my favorite. I like this jam, and I like this part.” Then I’m going to put on something else other than what I’m listening to. So if I put on five songs, you’ve got 15 to 20 minutes of music, max. That’s enough to satisfy you, where you’re either going to play your favorite song again, go to another song you like, then move on to somebody else. Young kids’ attention span… they’re not going to listen to a sixty-some minute record with 15 songs, and they’re five minute songs. We wanted to keep it down to every six to eight months release a fresh EP with five or six songs, like five songs with lyrics and one instrumental, and keep all our friends and fans and music lovers more interested in less amount with more content.

Discussion

No comments for “Interview: Al Anderson”