Will Oldham has been steadily releasing records for nearly two decades now, under different names including (rarely) his own, Palace Brothers, and, for most of the last decade, Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy. His music receives much (well-deserved) critical acclaim: for example, his 1999 album I See A Darkness – the title track of which was covered by the late Johnny Cash – was ranked as the 9th best album of the 1990’s by the influential indie-arbiters pitchfork.com, who say that it “confirm[s] that Oldham is indie’s detached and brilliant DeNiro.”

The following is the transcription of a phone conversation with Oldham on 9/20/10, and formed the basis of a preview article for his 10/27/10 concert in Santa Ynez, California as part of the Tales From The Tavern series.

Jeff Moehlis: I want to start off with something a little bit tangential to your upcoming show in California. In particular, I think it’s cool that you took the cover photo for Slint’s Spiderland album. Did you have any idea at the time that this album would be so “important” and influential?

Will Oldham: Of course not. I don’t know what else to say [laughs].

I think the record was completed and came out essentially after they stopped playing together. They sent me a copy wherever I was living at the time, I don’t remember, I think I was living in Madison, Virginia, and it was an intense listening experience. But, yeah, there was no way to know how it would trickle out to the ears of other listeners around the country.

You hear a lot of great and powerful music, and the assumption is always that it has a huge life ahead of itself, and most often it doesn’t. Most often great and powerful music does not reach a lot of people’s ears. So there’s no way of knowing.

JM: I read that you’re in the car on the cover of their first album [Tweez]. Is that right?

WO: That’s right, yeah. My father took that photograph.

They are trying to put together a Spiderland 20th anniversary reissue, and it wasn’t too long ago, maybe two or three months ago, Britt Walford, the drummer, and Todd Brashear, the bass player, and I went out to where that Spiderland cover was shot, and a filmmaker named Lance Bangs took some photographs and shot video of us swimming in that same spot, with the idea that it would be a part of this reissue. Although those fellows are, you know, at times they can be perfectionists to a fault, so it’s anyone’s guess whether or not that reissue will ever come out.

JM: So maybe it’ll be for the 30th anniversary instead of the 20th.

WO: There you go. That’s the optimistic way of looking at it.

JM: You mentioned your father having taken that photo. I’ve noticed several Oldham’s on the credits of your albums. I was curious – how would you characterize how your family has contributed to your music and career?

WO: Characterize it? I guess it’s just been essential, as with many friends… I can be, I guess, a bit introverted. So one way that I try to ensure that I get to interact with friends and family at all is by inviting them to participate and collaborate on the music work that I’m involved with. That ensures that I get some face time [laughs] because otherwise I might just get holed up somewhere.

JM: Another question about Slint. Did you ever record or perform with them?

WO: I think that, at the very very beginning, the idea was that I was supposed to play guitar and provide vocalizations, and at their very first performance, which was before they were called Slint – I think they were called Beads: Tiny Matted Tufts of Hair, that was their entire name – at that time it was before Todd had joined Slint, and Ethan Buckler of King Kong was the bass player – he plays on Tweez. The performance was at a Unitarian church that Ethan’s parents went to, just during a normal Sunday morning service, and I sat on the pulpit with them in front of the kick drum to keep it from sliding.

Then there was another time when Slint had a performance, I think it was at a place called Cafe Dog here in Louisville, and we rehearsed and would play this Neil Young song Cortez the Killer, and I was going to sing it with them. And then the police shut that show down and we moved it to another place that night called the Urban Alternative Homestead, and I believe that in the wee small hours, in hazes and fogs of intoxication, that we actually did do the song at one point. That was it.

JM: Are there any bootleg recordings floating around of this?

WO: I’ve never heard them.

JM: Are there any Louisville bands that you’re particularly fond of, either from back then or now, that maybe people outside of Louisville wouldn’t know so much about?

WO: There have been tons. Some bands… [laughs] I don’t know if it’s worth talking about bands that are gone and never made any recordings. There’s many of those. There was a band called Mr. Big in the 80’s that made recordings but didn’t release anything. Britt Walford had a band in the 90’s called Evergreen, he was in with other guys, I think Tim Ruth was the co-mastermind of that band. They made one record, it’s on Temporary Residence, I believe. It was on Carrot Top vinyl, and then Temporary Residence that put out the CD. It was one of the best.

The band Malignant Growth which sort of morphed into Fading Out – they made a full length recording. We reissued that on Palace Records. I love that record, I love that band. That’s led by a fellow named Brett Ralph, who later led a band called Rising Shotgun. I don’t think Rising Shotgun ever released anything, but they had some really great shows for a while.

King Kong, especially back in the early 90’s, was easily one of my favorite bands.

There’s bands now, like The Picket Line, that we made a record together, and Phantom Family Halo, and Bad Blood. These are bands that are playing around now that I get a lot out of.

There’s an old band called The Endtables. Drag City just reissued their recordings which were probably made in, like, ’81, ’82. The frontman for that was a fellow named Chili Rigot, who’s a painter now, but he was in multiple bands throughout the 80’s and 90’s. Two or three of his bands, I think, are represented on a Louisville punk compilation called Bold Beginnings, which is a really great comp. I’m not sure if it’s in print, but I think you can buy the MP3 version of it. I think it’s so exciting. Like I said, there’s two or three Chili Rigot bands on there, The Monsters, and Gull of Glee.

Then there was a band called Bodeco, which still plays every once in a while, kind of a hard swampy rock band.

There’s been so much good music here through the years. I’m sure it would be very difficult to name them all.

JM: I’ll definitely check some of those out.

WO: That Endtables record is really exciting. It’s cool that Drag City put it out. Of course vinyl is nice, but on the enhanced CD there’s a couple of video clips of them performing in ’80, ’81, ’82, something like that.

JM: OK, on to California. What should we expect from the concert in Santa Ynez?

WO: Oh, boy, we’ll see. Emmett Kelly is the Cairo Gang, and we made this record last fall, put it out in March, I think, and then started playing shows. We’ve done four or five small tours, and each tour we’ve done differently, with a slightly different repertoire, and a different lineup of musicians for each trip. I think there was even one trip where every night we had at least a slightly different lineup of musicians.

So the rest of the year, starting next week when we play in Chicago, we’ll have a six-piece group. I think the rest of the year – I think there’s three more small trips – we’ll have the same six people on each of those trips. But we haven’t all played together. We won’t until next week in Chicago. So I couldn’t tell you exactly what to expect.

The newest addition is a woman named Angel Olson, who’s based out of Chicago. Emmett’s been familiar with her music for a while, so we’ll bring her in as an energetic vocal ingredient, primarily. There’ll be a very strong rhythm section from here in Louisville, a drummer named Van Campbell and a bass player named Danny Kiely. Danny’s also played with The Picket Line, he’s on that Funtown Comedown Picket Line record. Van has a group called Black Diamond Heavies, which is a duo, him and a guy who plays Fender Rhodes. They’re a pretty heavy rock band that energizes the whole audience. He plays a little bit of piano, he plays a little bit of organ, a little harmonium – a guy named Ben Boye who’s based out of Chicago as well. So there’ll be six of us up there. We’ll play a lot of these Wonder Show of the World songs, and then we’ll probably have worked up a few covers, then we’ve some new songs that we’ve written, and then we’ll play some older Bonnie Billy songs as well.

JM: You mentioned Emmett Kelly, and of course you two released the album just recently. How has playing with him influenced your music?

WO: Well, to give a good answer would probably take a perspective that a greater length of time would provide. Overall, Emmett is a positive and curious and proactive force in making music, and making it expand and feel good to play, and feel good to write, and feel good to record.

Emmett, just overall, brings more joy into the process from beginning to end than many folks that I have played with. He’s got a intense fluency with music, and an ability to translate language into music and back again, which helps us cut to the chase and get to where we want to go with the song or the performance.

Then we’ve written these songs together, and he challenges me rhythmically and melodically as a singer, and helps me to become a better singer, which at the end of the day is one of my driving forces in life.

JM: To put this somewhat bluntly, you’ve been at this a while. You’re 40 – I’m 40, also. More broadly, how would you characterize the evolution of your music over the years?

WO: Evolution… [laughs] Maybe I’m more of a creationist in terms of my life and music. I wouldn’t know how to characterize. There’s things that happen more naturally as time goes on. And I think for the most part that’s for the better. There’s things that, just through practice, and practice, and practice, and through doing become second-nature, which allows me to take a step further that I couldn’t have taken before.

But, you know, at some level it’s still stepping toward the same goal, and maybe if the goal was in the center of the circle, instead of circling it, it’s like a toilet flush – I get closer to it I feel on each revolution, but if and when that center is reached, that’s probably just going to be the end. Or the end will be the center, the flushing you know, but it’s circling and getting closer and closer and closer, I feel like, to this thing that music is to me. It’s just because of doing, getting up everyday and doing it, getting up every day and thinking about music and communicating with musicians and making records and writing songs and playing shows and rehearsing and listening and listening and listening to music. It just gets closer and closer to that thing that music is to me, I guess.

JM: I’ve heard your music described many different ways. I’m wondering, as far a genre for your music, how do you perceive it? Or does it matter? Should we put a label on these things?

WO: [slowly] I don’t think that it matters. Of course people ask me that question all the time. Everybody asks it. You know, people at customs when you go into a foreign country to play music, they’ll say, “You play music? What kind of music do you play?” And usually I try to think of the thing that relates best to my perception of whoever is asking the question. So I could say it’s underground music, it’s country music, it’s folk music, it’s R&B, it’s jazz, it’s gospel music, it’s experimental music, or innovative music – that’s one that we’ve been joking about lately. But it just kind of depends on who’s asking and why, why are they asking, why does anyone ask. It’s just what it is. Whatever element people bring to it, but then it’s whatever element people perceive.

You know, you can listen to country radio, and you think “what the hell makes that country music?” It’s just because they decided to play it on that station instead of the pop station. Or there have been songs that have been hits for R&B artists and country artists in the same twelve months in the last ten years. What makes it one thing or another? It’s pretty random. So, I don’t really understand.

There was a record store I went to once, I think it was in Texas somewhere, or Louisiana, where they just put everything alphabetical. I was so relieved, you know, because sometimes I want to find something, and I don’t know what kind of music it is. It’s a record I’ve heard, it’s a record I like. I go in and try to buy it, and I don’t know where to look for it. Because it just depends on how someone classifies it, and to me it’s just music. I never think, I want to hear the sounds of blackness right now, I just think, ooh, I want to hear this person’s voice.

JM: I get the impression that you don’t think, OK it’s time to make my country album, or it’s time to do a folk album, or whatever. You just do what you want to do, right?

WO: And what’s possible at any given time. Part of it is what I might want to do, but then also sometimes someone can present an opportunity to play with a person, or to record with a person, or to work on a certain kind of song. So if that’s possible, then that’s where we go.

JM: Which of your albums would you recommend to newcomers to your music?

WO: I guess it would depend on the newcomers [laughs]. There’s the rare person that I would say listen to something like Get On Jolly, which is the collaboration with Mick Turner, Marquis De Tren. That’s very dear to me. But most often I would… I don’t know, I’d try to figure out what the person’s ear is before I would recommend something, because I could recommend the record [Superwolf] with [Matt] Sweeney for one thing, and the record [The Brave and the Bold] with Tortoise for another thing, or the record [Ask Forgiveness] with Greg Weeks and Meg Baird for another thing, or The Letting Go, or Lie Down in the Light. They have a sweetness to them that might be good for old people, I don’t know.

JM: Do you have a personal favorite album?

WO: An all around favorite… Arise Therefore has always been a very important record for me. And Joya, Ease Down the Road… it’s just different for different things. One thing that I love about Ease Down the Road and Greatest Palace Music is the amount of people that play on both of those records. That meant I got to spend – you know as I was talking about at the beginning of the conversation – quality time with people that I love, like, and/or respect, and make music with them, and interact with them. So it’s different for different…

Musically, sometimes I feel like a certain record might have gone someplace that I didn’t have an idea that that was possible for me, say The Letting Go or the intensely collaborative records like this record with Emmett, or the record with Matt, or the record with Tortoise, or the record with Mick, or the one with Meg and Greg. So each one is very significant to me, but I guess at the end of the day I guess I don’t have a favorite favorite. I mean, on each day I have a favorite, but it’s different each day.

JM: You mentioned a lot of people you’ve worked with. How do you decide who to work with, or how does it happen that you collaborate with different people?

WO: I mean, each case is as specific as the individual or individuals involved, I guess. You know, with Ask Forgiveness with Greg and Meg, who are both in the Philadelphia-based group Espers, I think I’d seen them play in Santa Monica opening for the Incredible String Band, I’d heard about them, and I was just very moved by the set. I started listening to their records, and it was something that when I would listen to the Espers records, it’s like the color powder blue. I can’t control my feelings about the color powder blue, it sort of disarms me and melts me and makes me feel great, and so it was with the Espers’ recordings. Every time I would hear them, I would just get excited, and sometimes I would have to call a friend and just share my feelings, because I didn’t know what else to do with the feelings.

So then I started to think about how can I… You know, I want to do something with these feelings, so what’s a good thing to do with them, well maybe to try to be in the same room, and have the energy circulate instead of having it sort of end in me. Have it circulate around and see what happens. There was a group of songs that seemed appropriate to present to them, and they were in agreement, and so we tackled it.

JM: Many people have come to know your music through Johnny Cash’s cover of “I See A Darkness”, and that is probably your best known song, in part for that reason. Do you have any reflections on that song in particular?

WO: Sure. Fortunately, for the most part, it’s a relatively interesting song to play and to sing. It can creep into the set without stomping on any of our buzz onstage. At the same time, each time we play it we’ll probably play it a little bit differently, and each time I think about it as it’s being sung, I think about the lyrics a little bit differently.

Sometimes it’s frightening, and I wonder if it’s how… I don’t know, sometimes, the chorus… [pause] I don’t know if it has a subliminal effect, like if I keep singing it, and if there’s a reward, meaning a reward even of energy from the audience for singing that, is this sort of dark vision, to dumbly paraphrase, being rewarded [laughs] and does that feed itself and make for a dark or darker vision as days go by? When maybe we get to age 40, any light that we can grab should be grabbed. I love the song, and sometimes it’s a little troubling. My relationship to the song is a little troubling.

JM: Who would you say have been your major musical influences?

WO: Different people at different times. In my teens there were people like Phil Ochs, or The Misfits, and Samhain, then Danzig, The Mekons were huge, Madonna was huge, Lou Reed, a bunch of Lou Reed records. There were Jesus Lizard live shows, more so than their records.

Then I probably started playing music, and so then it would be people that I would be playing music with. You know, my older brother [Ned] was huge, Dave Grubbs was really big, influential to me. But then people I would play with: Mike Fellows, and Sweeney, and my older brother, and guys who played in the Anomoanon – Aram Stith, and Jason Stith, and Jack Carneal.

I remember I lived in Baltimore for a while, and there was a band called Quix*o*tic, which had the Billotte sisters, Mira and Christina. Mira’s gone on and played with White Magic. During that time, both of the Billotte sisters were strong influences.

Also, throughout the years, really since I was a teenager, most of the records of Leonard Cohen, and then in the last fifteen, twenty years maybe, all of the records of Merle Haggard. In the last ten years, R. Kelly has been pretty important. The Fall definitely were. More recently, June Tabor, and Suzanna Wallumrod, who is a Norwegian singer making records now.

JM: Quite an eclectic bunch.

WO: Just keep listening.

JM: You mentioned Lou Reed, who is one of my personal favorites. Did you get a chance to meet him as part of the business or anything?

WO: No. I had a dream once that I met him, which is, you know, just about the same. But, I can’t think of a time…

I think that the last record of his that I listened to a lot was New Sensations. And every once in a while I think, oh that’s a pretty good record, but for some reason I won’t play it again. Like I think I really liked Songs For Drella, listening to it a couple of times, but I think I got disillusioned.

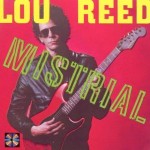

When Mistrial came out, it was just such a terrible, terrible record. And then when New York came out, I thought it was a mediocre record but everybody was loving it so much. I just felt like this is sort of a bad energy zone, to be paying attention to somebody who feels like he’s done something creatively important and it doesn’t interest me. And sort of that’s the direction that his music went from then on, this sort of somber, self-important,…

It was more the lack of sense of humor, and the lack of experimentation that were very much a part of his records from the Velvet Underground on, up to New Sensations. After that, it was more this kind of austere poet laureate, just sort of speaking his lyrics and claiming that he could never sing when. But if you listen to his records you realize that the harder he tried the more powerful the performance has been.

JM: I do like The Raven.

WO: I haven’t listened to that one, but I’ve heard it’s good.

JM: But I’ll admit I don’t put it on often. The 2CD version, which has more experimental stuff, is good.

WO: I should listen to that.

JM: There’s an author [Jason Hartley – the book is The Advanced Genius Theory: Are They Out of Their Minds or Ahead of Their Time?] who had this idea that certain artists are so good that they leave their listeners behind, and Lou Reed was used as an example. I just read the first bit of it, but it addressed exactly the experience that you’re describing, that the new stuff doesn’t seem as good, but that people like Lou Reed are operating on a higher plane that most people just don’t understand. I don’t know if I buy that.

WO: For some artists, there is an essential relationship with the audience, even though Lou Reed was always vocal about, you know, “Fuck the audience”. At the same time, he needed to have a relationship with the audience, because that’s how we make a living. We make a living by having a relationship, having an exchange with the audience. And then probably at a certain point, like with New York, once he reaches a certain kind of critical acclaim, at a point in his life and his work when he doesn’t have anything to prove anymore, he’s sort of done all that he could want to do. And financially, if he just keeps his pace he can make live guarantees and he never has to worry again about pleasing an audience. And so that relationship is kind of over at a certain point, and when that’s over, yeah, you have to be in love with the person in order to get something out of listening to their work as it goes on. If they don’t have to care about us, then it’s kind of a masochistic relationship that you begin to have with those artists.

JM: Here’s a question that, whenever I do interviews like this, I ask. What advice would you give to an aspiring songwriter or musician?

WO: [laughs, long pause] I don’t think that there’s any broad or sweeping advice that I would have to offer to anybody. If someone said, how can I finish this song, then maybe I could say something.

I’m not sure that I have the same motivation as someone else who writes songs or plays music. In my experience, I’ve found that my advice, in terms of making records and making music, doesn’t really get communicated, or doesn’t really apply to folks.

I don’t know. It would depend on the individual – man, woman, young, or old, and what their motivations were, and what their practices were. I think that there’s very few people that I would have advice that would be valuable to them. [laughs] I have a particular way of doing things, and most people think it’s retarded. They’ll ask me, what would you do about this – they’re writing songs – and I’ll say, and they’ll look at me like I’m from Mars.

JM: Well, this of course begs the question. You say that you have a different motivation, and a different way of doing things. What is your motivation for doing music? I guess you covered this earlier, how you have an ideal that you’re trying to reach. Is this a fair characterization?

WO: Yeah, that’s the motivation. Once I accept the fact that I make music for a living, I make music, that’s what I’m involved with, that’s where – by accident, by design, by privilege – that’s where I’m situated in this life. So once that’s written and the truth, then what I said before about the spirals is how it works. And then, getting to the place where that’s the truth…

It was abandoning the illusion of choice at a certain point, and realizing for one reason or another I grew up with an older brother who was a really good musician and was very curious about music, and then in a large, very very strong, very inventive, energetic musical community here in Louisville. And at same time I was studying theater, intensely studying in the history of performance and improvisation and movement and all these things, and I realized at a certain point when I was 21, 22, that that’s my quiver, that’s my bag of tricks. That’s what I have.

If I’m going to do anything that has breadth or depth to it, it sort of has to be in the conveyance of some kind of language and art, and melody, and working in that practice, because I know that stuff. It’s almost a responsibility – more than a responsibility, it’s just, those are my circumstances.

I can imagine, oh, I’d love to be a great chef, I’d love to be a great plumber, or a great lawyer, or I’d love to drive trucks. But I didn’t have any of those experiences. That wasn’t, at that point, woven into the fabric that was me. It was just about this relaying of text, this music. Music and acting, to some extent as well, of course. So the motivation was just to try to be true to the cards that I’ve been dealt.

You know, I think some people are like, ah, I’d like to be onstage, ah, I would like it if people look at me, or I could write a better song than that. Or whatever. I’ve never been able to relate to the term “rock star”, or to these video games, or even to the love of the audience. None of that makes any sense to me at all.

I feel like it’s my trade, and part of the trade is having a relationship to the audience, but it’s not necessarily their attention or their approval, it’s more. Have we established a strong enough communication and can we continue with that? And if we can’t, it either has to be fixed or abandoned. And if it’s abandoned, hopefully that’s at the point of retirement and/or death.

I don’t have anything else to do. I don’t have any other well to draw on. I don’t even think I would be good at Dairy Queen, you know, working at the drive-through window, I don’t think I would be good at it. I don’t think I could function doing that. So I don’t know. I wouldn’t know what else to do.

JM: One phrase you said made me think that maybe this is advice to an aspiring songwriter: to be true to the cards that you’re dealt.

WO: Yeah. Even as a kid, you know when we were studying world history, and studying European history, and learned about the guild system and apprenticeships, I thought, gosh, that makes sense, you know?

You have your internal identity and your external identity, and your external identity is shaped by everything outside of you, and you can push and pull with that, but at a certain point you have to yield to that in order to maintain the health of your internal identity.

Some people get dealt cards that are completely fucked across the board, and there’s no way they’re ever going to have a winning hand, and there’s no justice in the world. You know, there is no justice in the world. And some people are dealt cards that if they keep playing them, keep playing them, and bluff sometimes, you know they can keep their head above water. But there isn’t any justice. Some people are dealt a fucked hand, where their internal self is so strong, and they might be capable of writing – and they are, many people capable of writing such good songs that we won’t hear, that or we won’t even recorded or performed, even in the way that reveals the true strengths of the songs – but that’s what you do. You have what you have.

JM: What is the songwriting process typically like for you, or is there a typical?

WO: There isn’t a typical. It would be different for each song, or each set of songs.

JM: Do you set aside time to write songs, or do they just sort of bubble up? Are you working on a bunch of different songs at the same time?

WO: Yeah, usually I’m working on a bunch of different songs at the same time. Usually I set aside time for them to bubble up. In setting aside time, I find that you can prepare yourself… Say, you say I’m going to work on writing songs every day, for an hour and a half between 9:00 and 10:30 in the morning, or between 10:00 and 11:30 at night, or whenever you have access to no intrusions. If you keep doing it, it can maybe start off uncomfortable, but eventually your mind starts to become comfortable with the idea that you’re letting it find its way to and through songs at that time. So your subconscious or your semi-conscious state will start to make choices during the days and weeks that make that into a valuable time. So that you’ll realize, oh, I didn’t drink that coffee or I didn’t fuck that woman, because I needed to write this song right here. Or I didn’t take a phone call from my brother because it was going to be upsetting, so I could get to the song. Or I did take the phone call from him because I needed to get this stuff off my chest in order that my brain would be free to allow the song to be worked on.

JM: What are your plans, musical or otherwise, for the near future?

WO: I’d love to record a few singles, you know seven inches, before the end of the year. And then we have these three Bonnie Billy and the Cairo Gang trips this year, in 2010. And then I’m also working on some songs in collaboration with somebody, which should be done in the next few days, I think.

And then I’m trying to do something that I can’t remember ever doing before, which is that at the present time, by Christmas or by New Year’s, there are no plans after that. And I’m going to see how long I can go without making any. Usually at this point I’ll have a recording session booked, or a tour booked in February, March, even May by this time of the year. I’m trying to see what happens if things are open.

JM: Do you want to set the record straight on anything about your music or career?

WO: I don’t know. Can you think of anything that’s a possible misconception?

JM: Well, one thing that springs to mind is that people think of you as a very serious, and perhaps even dark person. But I get the impression that you’re actually pretty funny, and enjoy things as well. Is that true?

WO: I don’t know who gets that impression. There are days that are unbearably heavy, and there are days that are just wonderfully ebullient, and then most days are probably a mix of the two things. Both are true. [laughs]

Comedy is very important to me. I have tried to foster working relationships with Neil Hamburger and Galifianakis, and Tim and Eric, and that’s because… Making a record of course is intensely rewarding, and there’s a lot of work that goes into it. But the great thing about comedy is that the reward at the end is laughter. I’m one of those people that when I know a funny joke, I usually can’t tell it, because I’m usually

laughing too hard to tell it. So I’m not the best joke teller. But that’s a fault that I can live with.

[some chatting, wrapping up the interview…]

JM: Where am I reaching you at? Louisville?

WO: I’m in the place where I do some work, which is just a few blocks from my house. A work place.

JM: Do you record stuff there also?

WO: Yeah, we rehearse over here, and listen to music over here. I don’t have a record player where I sleep. I don’t have a landline, or a computer or anything over there. All that stuff is done over here.

JM: You mentioned your older brother Ned. You also have a younger brother Paul.

WO: Paul and I have recorded a shitload of music together. He’s recorded I See A Darkness, Ease Down the Road, Superwolf, Get On Jolly. I know there’s more in there. And he’s played a lot of bass, and he’s stopped engineering. Now he lives in the Bay Area making guitars, he went to school to become a luthier, so that’s what he’s does now. But he still masters, he still masters our records. He’s an amazing mastering engineer, and a very good friend.

JM: How did you end up scheduled to play in Santa Ynez?

WO: Emmett’s mom [Carole Ann Colone] set up the show. She sets up shows at that place where the Tales from the Tavern is. She has a band there called She’s My Band.

Excellent interview. Thank you for asking such thoughtful questions.