Pianist Mike Garson performed over one thousand concerts with David Bowie, more than any other person. He joined Bowie’s band for the Ziggy Stardust tour, and played on the Aladdin Sane, Diamond Dogs, and Young American albums. He re-entered Bowie’s orbit in the 1990’s, and played on Bowie albums including Outside, Earthling, and Reality. You can hear Garson’s diverse piano skills on Bowie songs ranging from “Aladdin Sane” featuring his avant-garde solo, to “Young Americans” and its Philly soul splendor, to the frenetic “Battle For Britain (The Letter)”

Garson has also recorded and toured with a number of other notable artists, including Nine Inch Nails and The Smashing Pumpkins, and has released a number of solo albums. He has composed over 5,000 pieces of music in virtually every imaginable style.

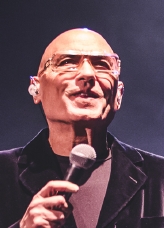

This interview with Mike Garson was for a preview article for noozhawk.com for the concert “A Bowie Celebration” at the Majestic Ventura Theater on 9/26/18. It was done by phone on 11/6/18. (Steve Rose photo)

Jeff Moehlis: What can people look forward to at the upcoming show?

Mike Garson: I’m very excited about this band that I have. It has four alumni in it, people who worked with David in the last few years of touring: myself on piano, Carmine Rojas on bass – he played on Let’s Dance, just a great bass player; Earl Slick who’s on lead guitar, who has been with us since ’74 and rejoined us in 1999 – he’s a great guitar player; and Mark Plati who is also a guitarist – he produced the Earthling album and Hours, and he toured with us in ’99 and 2000, 2001.

So we have all those guys, plus Bernard Fowler on vocals, who’s the Rollings Stones back-up singer for 30 years; then we have Gaby Moreno from Guatamala – she’s a powerhouse singer who sings the hell out of “Five Years”, which is one of Bowie’s great songs; and we have another singer Joe Sumner who’s amazing – that’s Sting’s son. He sings a song that David never sang, that we recorded in 1973 called “Lady Grinning Soul”. It’s an amazing song. It’s very high, in terms of the pitch – I think that’s why David never sang it. But it’s a great, great song.

So we have those three great singers, plus a great band. Earl Slick has a son who’s a drummer, and so we’re passing in down the generations. He’s a great rock drummer. He studied with one of Bowie’s drummers Sterling Campbell. So we have him. Plus I’m doing the “Aladdin Sane” song, which made me kind of well-known when I recorded it with David in 1973. It became an important track, so we’re doing that song. So I think they can expect a pretty good show. It’s very authentic. The band sounds like what we sounded like when we backed David up. It’s very exciting.

JM: How did you first meet David Bowie?

MG: I met him in ’72. He came for his first American tour, and he didn’t bring a pianist for some reason. He came with the Spiders From Mars – it was Mick Ronson on guitar, and bass and drums, and then he realized that he needed a piano player. coincidentally, I had played on an album for a jazz singer named Annette Peacock. She did an album called I’m the One, and I had played on her album. He happened to be a fan of hers – she was kind of an avant-garde singer – and he ran into her and she recommended me. So it was totally serendipitous and fortuitous and synchronistic. It was just one of these amazing things because I didn’t know who David was, because I was a jazz musician.

JM: That’s when joined him for the legendary Ziggy Stardust tour. What are your reflections on being a part of that particular tour?

MG: Life is a funny thing. Not knowing who David was or who the band was, it was like another gig for me until I realized that David was a renaissance man and a genius, and I started to get into it. But initially I just didn’t know, because I was a musician that just got called to play on people’s albums and do touring. I didn’t know I was going to be running into one of the greatest rock musicians of the century. It was a great band back in the day, and of course the audiences went crazy.

And his music still holds up. The joy of doing these tours is everyone sings every song, you know? Even if it’s a small audience or big, they’re singing the songs, and that makes it worthwhile for me to do these tours.

JM: You mentioned your piano solo on “Aladdin Sane”. Can you give a bit of background on that, and what sort of guidance David gave you on what to play for that?

MG: He gave me great guidance, because I played a blues solo first and he said, “No”, and then I played a Latin solo and he said, “No”. Then he asked me to play avant-garde jazz, like I had told him that I was doing on the jazz scene in the ’60’s in New York. I said, “Really?” He said, “Absolutely.” It was one take, and that’s the one that’s on the record. I never heard the track for 18 years.

JM: What did you think when you finally did listen to it?

MG: “Who is the crazy piano player?”

You know, it was one of those things that was bigger than me. It had to do with the time, and the zeitgeist of the time, and what was in the air. David had done the Ziggy Stardust album, now he was doing the Aladdin Sane album. He liked the idea of changing up the lead guitar to lead piano, because the piano is so important on that album, on the song “Time”, and “Lady Grinning Soul”, and “Watch That Man”, and “Let’s Spend the Night Together”. It was my first album with him. I used to always play a lot of solos on people’s albums, but here it was with a major rock star, and the rest became history. They just issued the 45th anniversary vinyl of Aladdin Sane, just a few months ago.

JM: Was it typical that he didn’t give you much guidance on what to play?

MG: He never micromanaged, Jeff. He always gave a vision, or nothing. Because whoever he hired, he trusted. So if he trusted you, he wanted you to give your magic to the best you could, and that was essentially how we worked. I was hired for eight weeks, and I lasted all those years – 19 albums later, and a thousand concerts that I performed with him. A few more than a thousand. It was unheard of, the way our paths crossed, and how our creative processes were very similar, and our thinking. I didn’t know it at the time, and I don’t think I appreciated it at the time to the degree that I do now, and I think I also took it a little for granted, for which I’m regretful. But that gives you some understanding that you’ve got to really, really appreciate life, because a person could die at any time, you know?

JM: After Aladdin Sane came Diamond Dogs, and I know that you were a very big part of that album. Where was David’s mind at, and where was your mind at for that album?

MG: There were so many days when it was just really me and him in the studio. He played most of the guitar parts. It was just like, “Didn’t I do enough on Aladdin Sane?” “No, I have more, and I want you to approach it different, but similar.” You have songs like “Sweet Thing” and “Candidate”.

The thing about David is he let me contribute anything that was in my bag of tricks, whether it was classical playing, jazz, fusion, romantic, anything that I had ever practiced he found a place in the hundreds of songs that I recorded with him. That’s why he was a genius. You would have to call him the ultimate casting director. David was so ahead of his time and so magnificent in his ability to create whatever he felt like, no matter what was going on in those decades in which he was creating. He was always cutting new territory, new ground. The guy had some magic that I think that the world has really appreciated even more in these last few years since he passed.

I think it’ll keep growing, because aside from everything else, he was just a great songwriter. I just went over to London and I played five solo concerts, and I brought up a singer or two, or a sax player, and I was just paying tribute to the beauty of the songs, without guitar, without bass, without drums. It was as powerful as if I was playing in Madison Square Garden, and these were small jazz-type clubs. The people ate it up with comparable applause to if I was playing for a hundred thousand people. It’s just that it was a few hundred. But the ratio of sound and applause was comparable. So it shows me people love his music, and I have found ways to bring out those songs without the use of all the technology, just the pure beauty of the melodies and chords and the lyrics.

JM: You touched on this already a bit, that David Bowie’s musical style changed from album to album. Do you have a sense of where that impulse came from for him?

MG: I think because he was a true artist, not just a rock musician. Any great artist… If you think of Miles Davis, the way he changed jazz. If you think of the way Beethoven’s music evolved. I know my music – I’ve written over five thousand pieces – has gone through unbelievable evolution, from the simplest pop to the most complex classical to a jazz piece to a fusion piece to anything. I think when a person is left to his own creative devices, and his own creative process, and not pressured by society to do what everybody wants, I think the music will come out. You sort of have to be able to get out of your own way. That’s the best way I could put it.

I wrote a jazz piece in the ’90’s – I never released it – called “Get Out of Your Own Way”. I was onto something at the time – and I didn’t have words, it was just instrumental – but I know that we tend to be our own worst enemies. So when we get out of our own way we actually do better.

JM: The next album after Diamond Dogs was quite a switch, the Young Americans album. We still hear the title track on classic rock radio all the time. What do you remember about the recording of that particular song?

MG: Well, you know, that riff and that piano part, and the way it starts out with the piano, that set the whole mood for that piece. We had, of course, Luther Vandross in the band, so he covered all those background vocals. David was being influenced by Aretha Franklin and that whole world.

What people don’t know, in those first three years – I must’ve done four or five albums with him between ’72 and ’75 – he fired five different bands. I was the only one that remained constant. Because from all my music training I was able to change styles with him. Most people, they’re either an English rock musician, a jazz musician, or a Gospel musician, or pop, or country. I loved it all, so I was able to move with him, and he never wanted me to do an “Aladdin Sane” thing again. He didn’t want another Diamond Dogs. I’m playing some of the simplest piano playing on that album, but very effective for those tracks. I just remember thinking, “Boy, this is a whole other thing. This guy really does not sit on his laurels. He moves, he changes, he’s quick.” That’s about it on that.

JM: In the ’90’s you came back into Bowie’s orbit. Two of my favorite albums from that time are Outside and Earthling…

MG: Me, too. Me, too.

JM: Can you tell a bit about the recording of those, and what kind of direction David was giving at the time?

MG: Well, the Outside album he specifically told me he needed to do for his own spiritual sanity, because he felt he sort of lost some of his integrity in the ’80’s. He probably really didn’t. He was rough on himself. But I think he felt that way a little bit, and he needed to freshen it up by doing this wild album that had a lot of improvisation and all that. He told me to my face, “Every musician on that album that I’m bringing in are the people that influenced me, and were most inspiring to me during my career. So I’m bringing you and Brian Eno and Reeves Gabrels. These are the people that I want to help inspire this music.” It was just a wonderful experience in Montreux, Switzerland. We just would improvise all day long, and he made songs from those things. We each got composing credit for contributing to that vibe. What a great time that was.

Earthling was a whole other thing. We did it in Philip Glass’ studio in Greenwich Village in New York. I just have great memories of “Battle for Britain” and “Dead Man Walking”. It was an amazing album. It was a little drum ‘n’ bass. I played a wild solo on “Battle for Britain”. He wanted me to listen to Stravinsky’s “Octet”, some crazy piece by Stravinsky. He told me to go buy the recording at the record store. I went down and listened to it, and he said, “Now, build a piano solo that has the vibe of this eight-piece octet that Stravinsky wrote for.” I mean, think about that – a rock musician telling me to do that. Then, that solo is just another wild solo. Again, he led the way. A total visionary. I’m very grateful that he was in my life.

JM: What was David Bowie like not just as a visionary musician, but as a person?

MG: Very, very warm. Very, very interested in people. He had a hilarious sense of humor. You know, you live on a bus for years together with a guy, and you’re sleeping six feet away in these bunks, you become very close. He was a friend, and I still miss him. But he was very warm.

He let you be yourself, and that is something I can treasure for my whole life, because not every artist let’s you be yourself. When I worked with him, especially when we did piano and vocal things alone as special events, it was a duet. It wasn’t a pianist as the accompanist. We were working together. He never made you feel you were smaller. You were part of the unit of the group, and not too many artists that I’ve worked for have that kind of a mentality. He understood the energy connected with groups and people. And I’m thankful for that, for sure.

Discussion

No comments for “Interview: Mike Garson”