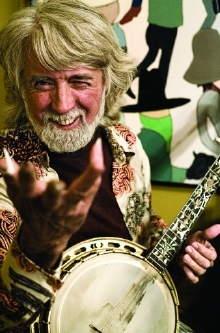

Multi-instrumentalist John McEuen has been playing music professionally for over forty-five years. A key member of The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band for much of that time, he was the driving force behind their classic 1972 album Will The Circle Be Unbroken, which had the band collaborating with bluegrass and country-western legends like Maybelle Carter, Doc Watson, Earl Scruggs, and Merle Travis. McEuen has also recorded or performed with a staggering array of other artists over the years, and his production credits include the Grammy-winning Steve Martin album The Crow: New Songs for the 5-string Banjo.

John McEuen and his sons Jonathan and Nathan recently released the wonderful album For All the Good, billed as The McEuen Sessions, which has been praised as amongst the best of the elder McEuen’s career. The following was for a preview article for the performance billed as John McEuen and Sons at the Lobero Theatre, Santa Barbara on 11/17/12. It was conducted by phone on 10/27/12.

Jeff Moehlis: What can the audience look forward to at your upcoming show in Santa Barbara?

John McEuen: Seeing something that is a very special evening, because the three of us don’t get the opportunity to play together that often. We’ve had twenty years of experience playing together, either as a trio, or me with Nathan, or me with Jonathan. The music these guys do is world class. And I get to hear it for free [laughs]. It’s an unusual combination of wonderful voices, not mine but theirs [laughs], and instrumental talents. I bring my banjo, guitar, fiddle, and mandolin, and they bring what they do.

It’s not like a folk music show. I don’t want to say that. This is a performance oriented show by a couple of young men that grew up in the music business and performing business, and they know how to play to an audience. So it’s really fun. I look forward to it. It’s really a good thing. These guys have their own reputations, especially in the area that you’re in, and I get to come in and do a show that’ll be unique to the Lobero. I’ve always wanted to play the Lobero. Never have, so this is a great opportunity for me, too.

JMo: It’s a great theater.

JMc: Oh yeah, best in town.

JMo: What is unique to you about playing with your sons, as compared with other musicians you’ve played with?

JMc: They can handle anything I do. The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band – tomorrow is the last of our 95 cities this year. And we do a definite order and type of music. I can’t play a lot of music that I like to play with the structure of the Dirt Band. But Jonathan and Nathan are such fine players, they can handle more complicated instrumental situations.

One thing that’s unique is to see the acorns doing, in my opinion, much more than the tree. And earning their own positions. This is not a couple of my kids playing with me. This is a couple of players that when the times are right and we can have a show together, it’s one of the best nights of music of the year for me. If anybody has liked what I do in the past 45 years… I don’t know how good what I do is. I leave that up to other people. But I do know this. I’m the best “me” I’ve ever been, as far as onstage. I do about 50 shows a year on the solo front, and this year we’ve had about 30 with the guys. But we’re looking forward to this – it’s been a little bit of time.

I’m lucky to be able to do this. We’re lucky to have the Dirt Band shows… for instance, the last ten shows have all sold out. The one we played last night was a small room, only 800 people, but it sold out three weeks in advance. That’s an exciting thing. We’re hoping that that will happen at some point with what Jonathan and Nathan and I do together. It’s a broader range of music, and more challenging and rewarding.

JMo: The album Will the Circle Be Unbroken is celebrating its 40th anniversary this year. I know you’ve talked about this, probably, for the last 40 years. But could you describe what the recording sessions were like for that album?

JMc: To quote Roy Acuff, it was a bunch of longhairs from California that didn’t know if they were old men or young boys or what. Because they were all covered with hair.

A bunch of iconic musicians of country music, the people that created a lot of the form, got together with some people who they didn’t know, really. And the times of political unrest, much more than know… I mean, Vietnam… let’s just say, there was a lot going on. In the era of Circle album, we had Kent State, we had marches where people were being killed, we had the bodycount on TV every night, things of that nature. But the establishment country music iconic people came together, and in the studio there were no politics. It was only music. It was a wonderful event, a wonderful joining.

I think the one thing that came out that was the most relaxing about it was finding out – although we were the nervous guys from California trying to come up to that mark, and we didn’t know what the mark was really yet – we found out that all of these people were fans of each other. Roy Acuff always wanted to record with Maybelle [Carter], and Doc Watson always wanted to meet Merle Travis, and Junior Huskey had played bass with, I think, all of them at one time. Never all at once. Vassar Clements had never played with Maybelle, but he’d played with everybody else. So all these people came together and it was like the pressure was off. We were just having the party, and they were bringing the food.

JMo: What did you learn from the guest musicians on that album?

JMc: One of the more important things learned is something exercised even on the album I did with my sons, The McEuen Sessions, which is a wonderfully received album. People that are very prone to being critical. People I know, don’t say things like, “Hey, I got your new album. It’s really lovely.” They all say things like, “It was about as good as the last one”, or something. I’m having people say, “This is the best thing you’ve done in 20 years. Records like this aren’t made anymore. This is such a fresh blah, blah, blah…” Well, one of the reasons that happens is all of the vocals and guitars, and most of the music on the album was first take. If we knew the song and we’re ready to record it, we’d go in and record. Roy Acuff said in 1971, “My policy in the studio, boys, is get it right the first time. And the hell with the rest of ’em.” Everytime you do it again you’re going to lose a little something. You may not even know it, but you’re goint to lose something. And he was so right. I follow that to this day. All my recordings, 8 out of 10 times, I try to hit the first take.

JMo: A couple of the guys that were part of that album, Earl Scruggs and Doc Watson, passed away this year. Could you reflect on the legacy of those two?

JMc: It’s not very many people that have a style of playing music named after them. You have Bob Wills Texas Swing music. But Scruggs style banjo is a comment that’s made about almost any bluegrass group. “I love the way that guy plays Scruggs style in that band.” It’s always referenced.

Doc Watson, on the other hand, was an innovator by being one of the first to play fiddle tunes on an acoustic guitar. And doing it with such force and dexterity and conviction.

Doc was an inspiration because he could take songs from different genres of music, and make them sound like they were written for him. Because he sometimes would do 30’s, 40’s, 50’s, or 1880’s songs, and they all sounded true coming from him. Earl was an inspiration because he created a form of music, a style called Scruggs style that has influenced thousands of people. I was very honored to play at his funeral at the Ryman Auditorium last March. I played a couple of songs that we’d recorded together. It was a very strange day for me. I wouldn’t have been standing onstage at the Ryman if it hadn’t been for that guy.

JMo: I read that Bill Monroe had also been invited to be part of the Circle album, but declined. What’s the story with that?

JMc: Bill Monroe didn’t know Nitty Gritty Dirt Band from The Doors, from anybody. He just knew we were on the pop charts, so we probably had drums, electric guitars, and trumpets. Bill Monroe didn’t need anybody. He didn’t want anybody. He did what he did. And if you didn’t like it, that’s just fine. If you like it, come on over. He didn’t understand what our intentions were, to represent the music well. And I’m proud to say that a few years later, Mr. Monroe came up to me at a festival and said, “Hey John. If you’re ever putting together another one of them Circle albums, give me a call.” It didn’t come to pass. But he understood after the fact.

JMo: When I was a kid I remember hearing the song “King Tut” by Steve Martin. And I’m guessing that’s probably the first time I heard you play. How did that song come together?

JMc: One night, Steve came to hang out at a Dirt Band show at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in L.A. We were playing a show there. It was a sold-out house, around ’78, whatever year “King Tut” was recorded. He came in the dressing room and said, “I’ve got this idea for a song. Have the bass go dum-dum-dum-da-dum-da-dum. Then you guys go ‘King Tut. King Tut. And the chords are kind of like a 50’s song. The feel, etc.”

So we spent about a half an hour, and we worked it up. We played it that night and the place went crazy. It was the first performance of it. And a week later we were in Aspen, and my brother produced the record. We did it in one day, recorded and mixed and finished it. And that was it. The record company didn’t want to put it out, which was very common. Record companies don’t make records, they distribute them, and sometimes they don’t think they can distribute something because it’s not like other things they already have. My brother sent out 20 acetates – in the day, those were plastic records that would only play about 25 times. He sent 20 major stations acetates, and within a week it had reached the Top 30. The next week it reached the Top 20. It then became one of the most requested songs on the radio, and forced Warner Brothers to release a single. It did a million and a half units.

JMo: You’ve been friends with Steve Martin for a long time, and produced his album The Crow. What were the sessions like for that album? Was he nervous, was he funny?

JMc: He was rarely funny. He was musical. Steve is very dedicated to doing things right. If you’re rehearsing something with Steve and it ends ‘dugga-dugga-dugga-dugga-da’, [he says] “OK, let’s do it again.” ‘Dugga-dugga-dugga-dugga-da.’ “OK, one more time.” This will go on for two hours. If he’s doing something, he wants to do it right.

He was pleasant. Let’s put it that way. He was concerned about being a musician surrounded by great musicians. But he had something they didn’t have. Original songs. Not that some of them don’t have original songs. But I really believed in Steve’s music. He had some wonderful banjo ballads.

There was one time where he had to count off the song. He was out in the studio, and this was like the second or third cut. And we go, “Steve, you’re going to have to count this, because you’ve got the tempo.” He goes, “OK, one, two, three, four.” I said, “Steve, when we do the count-offs in the studio, you have to leave the last number silent.” Because you can’t have the word hanging over in the echo that might be on an instrument, or bouncing around the room with a song starting. He goes, “Oh yeah, I get it. OK, here we go.” Everybody’s ready, and he goes, “One, two, four”. The song didn’t start, because everybody cracked up [laughs]. That was a good day.

JMo: Looking on your bio online, it said that you had played with The Doors. I was curious, what’s the story behind that?

JMc: Well, in the late 60’s, The Doors had some hits and so did the Dirt Band. We had the same agency, so we ended up doing at least 12, 13 shows with The Doors. A few on the West Coast and about ten on the East Coast. What was it like? Let’s just say that the two acts didn’t connect. And then two months later, we did ten shows with Bobby Sherman [laughs]. It’s been a very broad career. A very fortunate guy, I am.

I’d say that out of all of the things that I’ve done, one of the most musically fun is playing with my sons, like we’ll be at the Lobero. People aren’t going to want to leave. I won’t. I hope that doesn’t sound arrogant, but they’re really good. It’s a nice thing for Baby Boomers to see what the influence of the great music of the era that I and a lot of my audience are in, the late 60’s and 70’s, how that influence was absorbed and utilized and comes through with new music. From these two young guys that can hold their own with anybody.

I mean, one of the exciting things about when we were on the road last April, Jonathan’s getting phone calls from people wanting him to play guitar. Dave Mason, Dwight Yoakam, Robben Ford. You know, I’ve got him working for me! [laughs] That’s because they know he understands what they need.

Nathan has done a lot of things. You know, there’s a lot of jobs you’ve got to do in this business to survive, and Nathan’s done a lot of different types of performing, backing up people, singing harmony, different stuff and situations. And together, the two of them seem like brothers.

JMo: Imagine that!

JMc: I would say, in short, if anybody wants to see what people think of this music, just go to amazon.com and search under The McEuen Sessions. Those are the best reviews I’ve ever had on any album that’s been represented on Amazon.

They say that every review represents a couple hundred people who just didn’t write. What’s funny is we have twice as many reviews as the Dirt Band’s last album. I’m shocked by that.

JMo: What advice would you give to an aspiring musician?

JMc: Let me qualify your question to a young musician wanting to be in the music business.

Pay attention to the fact that if you’re going to be in the music business, remember it’s two words. Each word is equally important. You’re getting into to a business that’s you, and you will be the only one that cares the most about you. Others may sound like they do, just remember it’s your business. Learn everything about it. If you’re a songwriter, read The Songwriter’s Guide to Music Publishing by Randy Poe. Or quit pretending to be a songwriter. It’s that simple. People tell me, “I’m writing songs, and I want to know if I can get them out there.” Well, if you’re writing songs, I’ll talk to you after you read this book. Songwriting is a profession.

The other thing I usually say is to be as smart as a farmer. A farmer knows what crop to plant, he grows it, he has to harvest it, he goes through a lot of problems making it happen. But when he’s done, he knows how to distribute it. He knows how to market it. He knows what his market might be. A lot of musicians say, “Oh, yeah, we have a band, and we just finished the album and recorded it in the garage,” and they open the garage door and say, “Our album’s ready!” and nobody’s out there.

The time goes so fast. Don’t put an album out in September. You won’t get any notice. Everybody’s already got their editorial calendar committed through October and November. And Christmas and Halloween… there’s no space. And before you know it you’re going to be saying, “We put out an album last year.”

JMo: Do you want to set the record straight on anything about your career?

JMc: In 1971, I asked Earl Scruggs if he’d record with The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. He said, “I’d be proud to”. A week later I asked Doc Watson if he’d record with The Dirt Band, because we were going to have Earl Scruggs recording with us. He said, “That sounds like a fine idea.” My brother and I talked about that, and the next day he got Merle Travis lined up. Earl said he could get us Maybelle. Then we told the band, the other guys, what was formulating around week three. And seven weeks after I asked the first question, we started recording. So I would like the band to be proud enough of that fact in the same way they say, “I wrote this song”, or “Jimmy wrote this song”, or “We’re going to do a song now that I wrote” – referring to them talking. I’d like for them to be proud enough to say, “We’re gonna do a song from the Circle album that come about because…” Well, hasn’t happened in 40 years.

There’s one other thing. For years, a certain band member would say “Jackson Browne was in our band.” Jackson Browne did three shows with The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. He never recorded, never got paid anything, I don’t think. For 45 years I’m the guy that replaced Jackson Browne [laughs]. Not! [laughs] I’m going to regret seeing that in print, probably.

JMo: Where are you speaking to me from?

JMc: My room in Chico, California. At the end of a 95-city Dirt Band tour.

JMo: And going strong, it sounds like.

JMc: It’s never been better, I don’t think. The last ten shows sold out, in all different size rooms. In Canada, the front five rows of the audience are women that are 25 years old.

JMo: You must be doing something right, then.

JMc: It’s the kind of audience where you can say, “Hey honey, if you were ten years older and I was ten years younger, I’d be old enough to be your father.” [both laugh] Because I have a 23 year old granddaughter.

[Regarding the upcoming show:] If people like bluegrass, hot guitar, great vocals, and The Dirt Band, then they’re going to be very happy they went.

Discussion

No comments for “Interview: John McEuen”