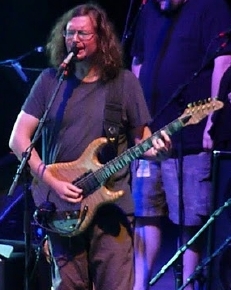

John Kadlecik (pronounced Kad-le-sik) is the lead guitarist for Furthur, the band which is keeping the music of the Grateful Dead alive thanks to original Dead band members Bob Weir and Phil Lesh, and Kadlecik’s Jerry Garcia-inspired guitar explorations.

Before joining Furthur, Kadlecik played in Dark Star Orchestra, which was notable – and quite popular – for covering full Grateful Dead setlists from throughout that band’s history. And before that, Kadlecik was a member of various bands including Uncle John’s Band, Wingnut, and Hairball Willie, the latter of which I can personally attest to having put on a great show in Ames, Iowa back in the early 1990’s.

The following interview was for a preview article for Furthur’s return to the Santa Barbara Bowl on 10/7/12. It was conducted by phone on 9/18/12. (L. Paul Mann photo, from Furthur’s concert at the Santa Barbara Bowl on 9/20/10)

Jeff Moehlis: Let me start by telling you that I saw your band Hairball Willie play in Ames, Iowa in about 1992.

John Kadlecik: At the Maintenance Shop?

JM: Yeah! For the uninitiated, and to refresh my memory, how would you describe the music of Hairball Willie?

JK: You know, we didn’t have the term “jam band” yet, so we just called it psychedelic rock, I guess. It was two guitars, bass, drums, a lead singer. We played a lot of Grateful Dead, but we were mostly about writing our own stuff. We definitely did a lot more non-Grateful Dead cover songs than we did Grateful Dead. The entire playlist at its peak was about 130 songs, including 30 original tunes.

JM: Could you give a quick synopsis of how you went from Hairball Willie to playing in Furthur?

JK: After I’d been playing with Hairball Willie for four, five years or so, a couple of the guys decided they wanted to do something else. The singer and the other guitar player left the remaining three of us to do what we wanted with it, with their blessing. We found another guitar player, a singer, and a keyboard player, and then we played around a little bit more for another year, but then that kind of imploded as well [laughs]. It just got to be too much work to keep all the people friendly [laughs], in a nutshell, at that particular point in time anyway.

At that point a chance came for me to join a long-running band, probably the largest Grateful Dead band in the Midwest area, which was Uncle John’s Band. Who also had been trying make a go of it with original stuff, but it was probably 95% Grateful Dead music. I did that for about a year, and unfortunately it was kind of a scene where I was the new guy, and the three other guys in the band were former new guys [laughs]. None of them were the original members, and there was some reluctance to push things. And I didn’t really think that a quartet was a large enough band to really do justice to Grateful Dead music. I pitched for them to hire a second guitar player, and maybe a second drummer, and they didn’t like it. So long story short, that didn’t happen, and I ended up quitting that, and starting a group called Wingnut in the Chicago area, which went for maybe a couple years. It was towards the end of Wingnut that…

I should say that, even from the Hairball Willie stage, we did a Grateful Dead setlist once as a fun idea. It was something I’d pushed for for a while, and finally got to do.

But I didn’t think that was the right band. So I had been kind of networking around the Chicago area, so fastforward again to being in Wingnut, I got introduced to the final piece for my idea of what would be a Grateful Dead tribute band doing their setlists. And it was a keyboard player [Scott Larned]. Two of the other members of the original line-up of Dark Star Orchestra also came from Uncle John’s Band, although the guitar player had been fired from it twice before I had joined. So I got introduced to him by the bass player. This is kind of a convoluted story [laughs]. I don’t know if there’s a way to straighten it out in a shorter way.

At that point Dark Star Orchestra came into existence, as just a Tuesday night house band. We all were maintaining our other bands on the weekends. I still played with Wingnut, the bass player still played with Uncle John’s Band, and so forth. But then it took off [laughs]. Two months in, we were selling out the room we were playing at Tuesday nights, and getting a line down the street of people wanting to get in. And then six months in, we had gotten the attention of Jam Productions, and they set us up for a weekend show at a nice theater, the Park West [in Chicago]. Then we started getting calls from out of town, and the rest is history, for the most part.

I briefly had a band called The Mix for a couple of years, that actually got signed to a recording contract, and released a record. That was with Melvin Seals and Greg Anton and Kevin Rosen.

But then, unfortunately Scott [Larned] passed away, and Dark Star Orchestra really needed to hunker down and play a couple years of 150 to 160 shows a year to catch up from a canceled past tour. So there was no time to maintain any other band, really. By the time the time came around again, Melvin had a pretty full schedule with his band. Although we had a bit of a reunion last December at The Fillmore. We did a benefit show for the Rex Foundation.

But then in 2009 I got an email from Bob [Weir]’s manager saying that Bob and Phil [Lesh] wanted to play with me.

JM: Did you think it was a joke at first?

JK: Yeah, actually I did. I thought I was being pranked by somebody, because it actually went straight to my spam folder. I was cleaning out my spam folder and there’s Bob and Phil, and I’m like, “Yeah, right. If this was a legitimate email it wouldn’t have gone to my spam folder.” But what do you know? [laughs]

JM: I have a good idea already, but what can we look forward to at the upcoming Furthur show in Santa Barbara?

JK: Well, I think there will definitely be some Grateful Dead songs [laughs]. There will also be, maybe, some of the new original material by Bob and Phil that we play. And a sampling of both Bob and Phil’s explorations post-Grateful Dead, some of the repertoire that they got into. Plus maybe some Ryan Adams [covers]. And, you know, some pretty adventurous jamming. I think we’re past breaking in the new pair of shoes, and now we’re just taking off full sprint.

JM: How and when does the setlist get decided for a given show?

JK: You know, Bob and Phil basically take turns taking setlists. And they often enlist the help of their closest managers. We get the setlist the morning of the show. No idea what we’re going to play until the day of any given show, typically.

JM: How many songs are you responsible for knowing?

JK: The total playlist, I think, is pushing 300 songs. I couldn’t give you an exact statistic.

JM: But there’s a lot to choose from [laughs].

JK: Yeah [laughs]. And they really seem to like to do tours where there’s minimal repeats across the whole tour. There are usually just a handful of songs that we’ll do three or four times in the tour. Most of them get played once [laughs], if they do get played. There’s maybe a hundred that we don’t even play on a given tour.

JM: When you play guitar, how do you find the right balance between having a Jerry Garcia sound and expressing your own individuality?

JK: As far as note choice goes, it’s always me. There might be some ornamentation stuff that comes in, and who I am is extremely influenced by Jerry Garcia, but I’m also influenced by Jimmy Page, or Trey Anastasio, or David Gilmour, or John McLaughlin, Alex Lifeson.

As far as my tone goes, I have kind of a bassline tone which can come across very Garcia-esque, but I’m very much a believer that there are only so many good tones. Jerry found one that’s actually lesser used in a lot of ways, but I think he found it. In the way any guitar player finds their tone. Their improvisational voice is a whole different animal. But there’s only so many good tones. I mean, there’s an infinite number of tones, but a lot of them are awful [laughs]. Like, Doc Watson had a tone, but it was Martin [guitar]. So that’s kind of the way I regard Garcia’s tone. We know of it because of him, thank God, but it’s not like it should never be used again because he found it.

JM: Did you ever get to meet Jerry Garcia?

JK: I did not get to meet Jerry Garcia, sad to say.

JM: But you did go to a huge number of shows, right?

JK: Huge? By whose definition? About 50 Grateful Dead shows, and about 15 Jerry Garcia Band shows.

JM: Do you have a favorite one, and show that really sticks out?

JK: The first night in Hamilton, Ontario in 1990 [laughs]. That one stood out to me. A lot of people are more hip to the second night, because it’s supposedly the keeper [of the vault]’s favorite “Scarlet>Fire” ever. But the first night was a stand-out night for me [laughs].

JM: What stood out for you?

JK: [laughs] There was a certain amount of subjectivity involved in that perception, I would say.

JM: Why do you think that the music of The Grateful Dead continues to resonate with generation after generation?

JK: You know, it’s timeless to begin with, and I think that’s by design. Or at least relatively timeless. There are some songs that clearly reference 19th and 20th century technologies, but most of the emotional content is stuff that can be traced in literature as far back as we can trace it, as far back as there’s written language.

And there’s good melodies. I consider it to be part of the folk tradition, and what I consider a defining characteristic of the folk tradition is the non-commercial, keeping-it-real aspect of the subject matter. Not worrying about whether singing a dark song is going to hurt album sales [laughs]. To me, that was the key essence of the folk music movement, speaking to the real human condition whether it’s a happy or sad story. To sing about death to help people come to terms with it. And, as I said, to not worry about whether it’s going to hurt album sales.

I don’t know. It’s hard to nail that down.

JM: What advice would you give to an aspiring musician?

JK: Well, the only good reason to make art is because you have to. Everyone has the perks that they appreciate in different proportions, but people who are focused exclusively on that, whose idea is to make a living at it or getting fans or attention or girls or money or whatever… The only good reason to make art is because you have to, or are compelled to.

With that being said, I would really just be paraphrasing Jerry Garcia from one of my favorite quotes of his. The three things a musician really needs to get them where they most likely can hang, maybe not make it as a rock star but at least be able to take music as a profession. Have something to say as an artist, is one. Two, have enough skills, or develop the skills you need to say what you need to say. Which is more important than, I think, making some sort of hypothetical technical standard. You know, if a punk rocker only needs to know one or two bar chords to get their music out, then that’s all they need. You don’t need to be able to play like Al Di Meola [laughs]. But they need to know those three chords, and at least get the guitar somewhat in tune, right [laughs]? And then the third thing is to be able to get along with other musicians. If you can get those three things down, you have got a pretty good shot, at least, of living a life as a musician. Not necessarily as a famous musician, which is really kind of like winning the lottery, in a lot of ways. But you get a chance to get your art out and live the life of an artist.

JM: How would you describe your relationship with the fans. Do you recognize the same faces night to night?

JK: Well, sometimes. Nights vary in how much attention I can pay to who’s in the audience [laughs]. I mean, I usually try and make that a key part of my performance, to be able to make eye contact with some people in the house. I consider it part of the way the energy and information exchanges.

But some nights are more chaotic than others, and require more attention just to keep it together. There’s not so much time to notice…

Sometimes I’ve given the river rafting metaphor. We, as a band, are the river rafter guide, and the audience is the people who signed up to be in the boat. They expect us to shake them around a little bit, maybe get them splashed on, but hopefully not dump them in the water. And definitely not have anyone’s head get dashed upon the rocks. So in the process of doing that, sometimes we can pay attention to the beautiful rainbow and the birds up on the cliffs, and sometimes it just takes every bit of concentration just to keep everybody from falling out of the boat [laughs].

JM: What are you plans, musical or otherwise, for the near future?

JK: I have a group that I play with [the John K. Band], based in the D.C. area. We don’t really tour, in part because generally I’m just sort of waiting to hear when the next Furthur run is [laughs]. Once that comes in, and any rehearsal time gets blocked out, then I can take what time is remaining and book some shows. It’s usually within a half day’s drive of D.C.

But who knows. Back in June we were asked to do a three night run out at Quixote’s [True Blue] in Denver. That worked. So we might try and do that again, maybe in the Bay Area.

JM: Do you want to set the record straight on anything, maybe something from your experience. You’ve been on both sides of the stage. You hang out with Bob and Phil. Is there any misconception that you’d like to address?

JK: In my experience both Bob and Phil have been really cool guys. They’ve been really cool to hang with and interesting to talk to, and seem to be still passionate about making music.

You know, it’s hard to speak to that. Different people have different ideas. Some people have these sort of fantastic ideas about what it must be like on the other side of the stage. You know, it’s magic when we’re making music, but all the stuff before and after is really just like any other job [laughs]. It has a lot of heavy lifting, a lot of traveling. I mean, I’m glad to say that me and the band don’t do any heavy lifting for this project [laughs].

I guess I have a personal frustration that there seems to be a lack of anyone knowing that I had a history before Dark Star Orchestra. I get sort of pigeonholed as a tribute band guy, and I actually started a tribute band because I was disgusted with tribute bands.

JM: Might as well do it right.

JK: Yeah, somebody’s got to go and do it right, and if not me, who? [laughs] But I’ve been writing and actually engineering and producing going back to the age of 15. I rented multi-track recorders and taught myself how to use them, produced sessions with my high school bandmates and mixed them down, all that fun stuff. Most of those songs from high school I wouldn’t want anybody to ever hear again, but I’m still playing some stuff that I was writing when I was 19.

JM: Where are you speaking to me from?

JK: I’m at home in a near-suburb of D.C., inside the Beltway.

Discussion

No comments for “Interview: John Kadlecik”