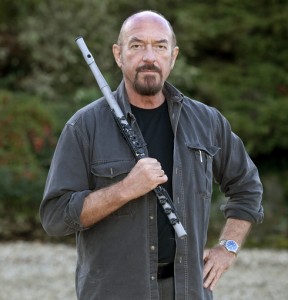

Ian Anderson is the frontman / singer / songwriter / flautist / acoustic guitarist for the band Jethro Tull. Jethro Tull’s first album, the bluesy This Was, came out in 1968, and their music rapidly developed with 1969’s Stand Up incorporating elements of English folk music and 1970’s Benefit embracing hard rock.

Next up was Jethro Tull’s classic album Aqualung, released in 1971 and regarded by many to be the band’s best. This included such Jethro Tull mainstays as the title track, “Locomotive Breath”, and “Crosseyed Mary”.

Jethro Tull followed with two concept albums, both of which reached No. 1 in the U.S. concert charts: 1972’s Thick as a Brick, and 1973’s A Passion Play, the latter including the not-universally-loved Winnie-the-Pooh-on-acid piece “The Story of the Hare Who Lost His Spectacles”.

Jethro Tull released many more albums, notable ones including the compilation Living in the Past (1972), War Child (1974), Minstrel in the Gallery (1975), Songs from the Wood (1977), and Crest of a Knave (1987) which somewhat controversially beat out Metallica for the Grammy Award for Best Hard Rock/Heavy Metal Performance. Also well worth checking out is Nightcap (1994), which has a different take on the material that ended up in A Passion Play.

Anderson recently decided to explore different possible life trajectories for the fictitious lad Gerald Bostock who had supposedly written the lyrics to the original Thick as a Brick album, resulting in the album Thick as a Brick 2. This interview was for a preview article for Anderson’s performance of both Thick as a Brick albums at the Chumash Casino on 10/18/12. It was done by phone on 10/9/12.

Jeff Moehlis: How do you find the right balance between “living in the past” and creating new music?

Ian Anderson: Well, that’s one of the reasons that I didn’t want to do a sequel to Thick as a Brick at any other time during the past forty years, because it would have been, for me, too nostalgic, too much living in the past. It was only when the idea occurred to me towards the end of 2010, and then subsequently after Christmas when I had the chance to revisit that notion, that I could really do that in a way that wasn’t just about nostalgia. It was a way of making an album that was for 2012, since we’d never have been able to record it and release it in 2011 – we already had all of our concert tours booked by then. So, you know, it was something that I knew was doable by using the vehicle of the young Gerald Bostock to ruminate on what might have become of him. What various things could have happened.

When I first thought of it, I wrote down fifteen, twenty possible outcomes, scenarios, career choices, whatever you want to call it. And I whittled those down to the necessary five, because I new that I would allot about ten minutes to each one of those possible choices, giving me the option of a couple of musical pieces, lyrically and musically, to get us from ’72 to now, and then examine a little more closely the “now” part of it. So suddenly I was able to do this without it getting wrapped up in nostalgia. I didn’t want to revisit ’72 in the temporal sense, just in the sense of using the identity of someone to catapult it forty years into the future.

JM: Is a healthy market for new progressive rock these days?

IA: I have no idea. I’m not in the music business in that sense. I just do what amuses me. I’m not a record company guy, or, like you, somebody who writes about it. I’m sure you can answer that question much better yourself. I have no idea.

Commercially speaking, it’s not the kind of project people actually would want to take on if they wanted to make a lot of dosh, because record sales… whether it’s catalog or new material, we’re talking about a tiny fraction of what it was thirty years ago, even twenty years ago.

JM: How did your goals change, both musically and professionally, from your first album This Was up through the recording of the original Thick as a Brick?

IA: Well, that was an exploratory period of time, because when we first began it was, to some extent, jumping on the bandwagon of white man’s blues music. So, we were in the company of several other bands of that era, Fleetwood Mac, Savoy Brown amongst them. We were people who played at the Marquee Club in London and played some of our own music as well as some of the classic blues repertoire. You know, there was nothing particularly original about it, but it was a good starting point in learning the basics of music through the improvisation within the 12-bar simple harmonic structure of blues.

But after a few months of doing that, I started to bring in other elements of music in the songs that I was was writing. And by the end of 1968, I had a bunch of songs that then became the Stand Up album released in the summer of the following year. That was a big step forward from the first album, just as Benefit, I suppose, consolidated the slightly darker, more rock riff side of things. And Aqualung, the more singer-songwriter part of the equation.

So by the time we got to Thick as a Brick, I mean, four albums into a career, I had a pretty good idea what I was doing. It just seemed interesting at that time to take a further step into what was then the cliche of progressive rock, because by then progressive rock had become prog rock, and Emerson, Lake, and Palmer, the early Genesis, King Crimson, and Yes had a lot to answer for. But we were having a little fun spoofing that kind of genre with Thick as a Brick, and I think the balance of joke and serious music really struck quite well on the Thick as a Brick album.

JM: At what point did you know that Jethro Tull had made it in America?

IA: I knew that by the time we got to the Benefit album, we were making quite an impact in America, headlining show in theaters. Through the Aqualung years in ’71, that was consolidated by the time we got to Thick as a Brick.

In unfortunate timing, we had at our manager’s behest graduated to playing arenas. That was a bad bit of timing. We should have stuck to the theaters with the Thick as a Brick tour, because it wasn’t something that translated into the arena atmosphere, where too many people… I guess people who were not really dedicated fans but were following Jethro Tull because by then we were a bit trendy, our music getting played a lot on the radio. And people came to the original Thick as a Brick tour in ’72, I think, expecting more of the Aqualung kind of approach, the more rock element in the Aqualung album, and what they got was a much more complex and often acoustic performance in Thick as a Brick, which they didn’t really enjoy. I felt I had a bit of a hard time trying to present that album, at least at concerts in the arenas in the U.S.A.

So it was a mistake, looking back on it, to allow my manager to push us into arenas. We should never have done that. I think really at any time. I don’t think Jethro Tull should ever have been an arena act, let alone a stadium act as we were in ’75, ’76. We should have just stuck playing theaters. It’s what we’ve always done best, and where I think my natural home is, on a theatrical stage or a concert hall stage, not in a sports venue or some multi-act festival in the middle of the summer where I feel we’re just not that kind of a band.

JM: What advice would you give to an aspiring musician?

IA: Well, the same advice probably as my parents would have given me. Don’t give up your day job. If you want to do it for fun, that’s great, and there’s nothing wrong with being an amateur musician. In fact, it’s a much purer way of making music because you’re not seduced by the culture and money, the greed and avarice approach to music as a means of becoming a star, either for financial or egotistical reasons. For some individuals it proves to be a curse, or even a cause of death, in the case of Jimi Hendrix or Amy Winehouse. People who can’t handle it shouldn’t really go there. It’s just too dangerous.

In reality, I think being an amateur musician, as from the Latin root “to love”, you do it because you have fun with it. I think you can enjoy your amateur status and be constructive within that. Should you get lucky and find yourself with a professional opportunity, well that’s a bonus. But start off by doing it because you love doing it, and you love doing it for fun. Playing for yourself, or to family and friends, or a small audience somewhere is just as reward bringing as selling a million records, or standing on a big stage getting screamed and shouted at. Arguably, the amateur status might prove up to be more enjoyable.

JM: Do you want to set the record straight on anything about yourself or Jethro Tull?

IA: There aren’t any misconceptions as far as I’m concerned. Jethro Tull is the name of the band that has released all of that catalog over the years, but as a group of individuals that we are 28 strong. You know, if you look at the historical perspective, 28 different people passed through the ranks of Jethro Tull. And I’m the guy that wrote the songs and sings the songs then and today, whether I go out under the name of Jethro Tull or Ian Anderson. I would hope, through marketing and promotion, if it says simply “Jethro Tull” on the ticket, then an audience would expect, and perhaps have a right to expect, that it is a best of Jethro Tull concert, where they’re gonna hear a broad selection of catalog items, the repertoire of the band over all that time. But if it says “Ian Anderson” on the ticket, I hope it suggests something a little more specialized, maybe the Orchestral Tour, or the Acoustic Tour, or the Christmas Concert, or a project like we’re doing now, the Thick as a Brick tour. But it’s not going to be simply general best of repertoire. So I say the name “Jethro Tull” for general repertoire tours, and when it says Ian Anderson on the ticket as well, then you can figure it’s a little more specific, the nature of the musical entertainment for that evening.

JM: Do you have any future plans with Martin Barre?

IA: Well, I don’t have any plans not to work with Martin Barre. It’s just that this year that he’s doing his solo projects and I’m doing mine. So we’ll see what 2013 brings.

JM: Where are you speaking to me from?

IA: The Southwest of England where I’m back home for six nights before heading off to start up again in San Diego.

From what is made that flute? :)