Belle and Sebastian’s early days are legendary. The Scottish indie pop band quickly recorded their first album Tigermilk in Glasgow in 1996 as part of the yearly project for a music business course at Stow College, pressing 1000 vinyl copies which they could barely give away.

But the law of supply and demand kicked in as interest in the band grew, thanks to the popularity of their follow-up If You’re Feeling Sinister which had a much wider release, and copies of Tigermilk started commanding prices in the hundreds of pounds. Meanwhile, the band laid low, with singer and main songwriter Stuart Murdoch refusing to do interviews for years. But the buzz continued to build, and the band cracked into the American market.

Fast-forwarding to the present, Belle and Sebastian has by now released eight albums and loads of EPs and singles, with their music drawing favorable comparisons to notables such as The Smiths, The Velvet Underground, and Nick Drake.

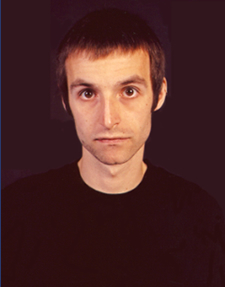

The following interview was done with Belle and Sebastian’s keyboard player Chris Geddes by phone on 7/8/13 for a preview article for the band’s concert on 7/17/13 at the Santa Barbara Bowl, the only California appearance of its tour.

Jeff Moehlis: What can we look forward to at the upcoming show?

Chris Geddes: It’s kind of a selection of songs from throughout the band’s career. I guess because we’re not plugging a new record at the moment, we’re not leaning too heavily on any one particular album. So we’re just playing songs from throughout the back catalog.

In terms of what the show is like, there’s quite a lot of people onstage. We’ve got a string section with us, so we’re about a dozen strong onstage. I guess it’s all singing, all dancing.

JM: Have you visited Santa Barbara before?

CG: No, I never have. We’ve only really been in the big cities in California. It’ll be nice to do a show somewhere a bit different this time.

JM: I think you’ll find that it’s a very beautiful venue.

CG: Yeah, I’ve seen the venue online. It does look really great.

JM: It looks like you’re playing a number of festivals on your current tour. How does it compare to play festivals versus a headlining gig like the one here in Santa Barbara?

CG: It varies a lot, just depending on what the other acts at the festival are like. Sometimes you can play a festival show, and if it’s the right audience or the scheduling is right and you’re in the right circumstances, you can feel like you’re playing to your own crowd, except there’s three times as many of them as you would normally play to. Then obviously, sometimes, for the crew and sound engineers the lack of control means it’s hard to work for them. But in general I really enjoy to festival crowds because people go to festivals to enjoy themselves. If you go to watch a band at a festival you’re kind of there with the mindset that you want to enjoy them.

JM: If you don’t mind going back in time a little bit to the time around Tigermilk, at what point did you realize that things were taking off for the band?

CG: It was quite gradual, really, because of the way we did things in the early days. I guess we did hold ourselves a bit back from the industry, partly because Isobel [Campbell, former singer and cellist with the band] and I were still studying, and partly because Stuart’s [Murdoch, lead singer and songwriter] health was still quite fragile. He was recovering from a long period with ME [myalgic encephalomyelitis, i.e. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome] when the band started. So I think it suited him… Especially in the U.K. I think a lot of bands make a really big splash with their first record, and then kind of struggle to go anywhere after that. In the long run it worked really well for us.

We came and played twelve shows in New York, maybe in like ’97 or ’98, and it felt like there was a little bit of a buzz about the band in New York, even at that point. It was quite amazing, to cross the Atlantic and to find that there were people over here who were into us. Then by the time we did our first proper American tour in ’98, the records up to that point had already done well enough on college radio that we were coming over and playing reasonable sized concerts on our very first tour. Which in a way it was maybe a little bit too much, too soon, because we probably weren’t really a good enough live band at that point to be playing the size of gigs that we were. It’s only probably since 2001 that we’ve really come together playing as a live band. That’s just because in the early years of the band we spent a lot more time in the studio recording than we did out gigging.

To go back to your question, in the first couple of years of the band, it was the fact that there was interest in the U.S. that gave us an indication that maybe things would go somewhere. There’s always small things like the first time you hear your own band on the radio at home. The BBC has always had music shows that played new music, music by either unsigned bands or bands on indie labels. You kind of knew that if you made any sort of record there was a good chance that John Peel would play it at least once, or someone like Mark Radcliff would give it a play. But the idea was that the record was getting played on radio stations over here [in the U.S.] was pretty amazing.

JM: How did your approach to recording the album If You’re Feeling Sinister differ from recording Tigermilk?

CG: There wasn’t much difference. The way we did both records, we’d rehearse the songs quite a lot before we went into the studio. It’s crazy now looking back on it, but at the time of If You’re Feeling Sinister it felt like we had quite a lot of time, because we had a couple of extra days compared to what we had for Tigermilk. I think Tigermilk was recorded and mixed in five days. If You’re Feeling Sinister, I think we maybe had eight days and then an extra day of mixing at the end.

I guess really the big difference was the engineer we were working with. We did Tigermilk with a guy called Gregor Reid, who was one of the house engineers at the studio Ca Va, which was kind of the one proper recording studio in Glasgow. Then when we went back to do If You’re Feeling Sinister, Gregor wasn’t available to do it, because he was working on a Pastels session. So we worked with Tony Doogan, who was the other house engineer, and that obviously was the start of a working relationship with Tony that has gone on for fifteen years or more. It was our good fortune that the studio in Glasgow had two young engineers at the time who were both great people to work with. By circumstances it just ended up being Tony that we’ve had the long partnership with, but Gregor was a really great engineer and a great guy to work with as well, or Tigermilk wouldn’t have been as good of a record as it was.

JM: Jumping ahead a bit, I find it curious that you had Trevor Horn as the producer for Dear Catastrophe Waitress. How did that happen, and what was that experience like?

CG: The experience of working with him was really good fun, because he was an engaging guy to be around. His approach to producing the band was different to what I thought it might have been. I guess we perceived him as a big Pop guy, a guy who a lot of his records are about programming and stuff. Obviously, he made some of the first hip-hop based records in the U.K., you know, sample-based records with the Art of Noise. I think I thought he might have done more programming and stuff on our record than he did. But I think his philosophy for producing the band was almost not to try and change the sound. I think he was very conscious that the band had an audience who maybe wouldn’t like it if he came in and put a big Trevor Horn stamp on the sound.

His approach to producing the band I guess really was just all about putting us in his studio and working with his engineers. We were fantastically well looked after in the studios, with great facilities. We did some weeks in his studio in London, which was the old Island studio where Bob Marley had recorded, and stuff like that. So working in the studios was really great, and spending a few weeks feeling like you lived in West London was really great as well.

Yeah, it was a really enjoyable record to work on. It was a record that everyone in the band brought quite a lot to the table. It’s got some of Stuart’s best songs on it, I think. Mick [Cooke] does a really amazing job on the orchestral arrangements, with big inputs from the rest of the band as well. Certainly in terms of doing the orchestrated stuff, we probably wouldn’t have been so bold with that if we hadn’t been working with Trevor.

He had a guy Nick Ingman who has done arrangements on a lot of great records. Nick was kind of the conduit between the band and the orchestra, which helped a lot. The orchestral players were top-notch players, because they were the folks that always play on Trevor’s records. So he did really put together a high-end team for us to work with that was nothing like what we’d worked with before in making records in Glasgow.

I suppose it came about quite randomly. I think the first time we played at Coachella the lady that was looking after our dressing room by coincidence was also Trevor’s housekeeper at his house in L.A. She just kind of mentioned that he knew the band, because I think one of his daughters was a bit of a fan. I think he kind of knew our records, and sort of thought that the songs are OK but the production… he just tried to polish our sound up a little bit.

JM: I’ve read that the band will be working on a new album after this tour. Can you confirm that and let us know what we can look forward to with that?

CG: Yeah, that’s very much the plan. Because of personal circumstances with people in the band, with Stuart working on his movie [God Help the Girl], and Bob [Kildea, bass and guitar] and Stuart both having had new babies recently, we haven’t gotten together and worked on any new music in the run up to the tour. But the plan is, as soon as we’re back home, to get in the rehearsal room and start writing stuff, and see what the writers have already come up with and start working on new music.

Because we haven’t really started yet there’s nothing I can really say that would shed any light on what a new record might be like, or what kind of direction things might take, or anything like that. But there’s a definite plan to start on new music as soon as the touring is finished.

JM: Here’s a question you probably don’t get very often. I understand that you have a degree in physics, and it turns out that I do as well. My question is, how do you think your education in physics still influences your worldview?

CG: I guess I believe in science. I believe that that’s the way you get factual knowledge about the world. If you want to make rational decisions about things, they should be informed by evidence. I guess that’s kind of how it’s shaped my worldview.

I must admit, to my shame, I’ve probably forgotten most of what I learned in the degree, certainly in terms of being able to do the mathematics. I mean, I can still sit and read a popular science book or an article in New Scientist and get something out of it, but I very much doubt if I could even do first year undergraduate physics these days, actually do the math.

I guess if you did cosmology, modules in that sort of thing, and quantum physics, it gives you an appreciation of how big and strange the whole universe is. And also what a miracle it is that through evolution taking place on Earth we ended up with brains that in some way are able to comprehend what’s going on on a really big scale.

It’s a better conversation to have on the tour bus after a couple of beers than it is in the middle of the day. [both laugh]

JM: To get an idea of your musical interests, when Belle and Sebastian curated the 10th All Tomorrow’s Parties festival, what artists did you personally push for to be on the program?

CG: The one who was most important to me was Mulatu Astatke, the Ethiopian vibraphone player. It meant a lot to me that he was there. I’d been introduced to his music a few years ago by a good friend, and then obviously there’s been quite a revival of interest in his stuff in recent years through the use in the Jim Jarmusch film [Broken Flowers] and those Ethiopiques reissues. We saw that he started touring in Europe a little bit, and had done some gigs in London. To get him to come along and play was great. I really enjoyed his show. It was kind of the highlight of the weekend. That was definitely my favorite thing from that weekend.

JM: What advice would you give to an aspiring musician?

CG: If it was to be something that was directly applicable to my own career, it would be to hook up with the best songwriter in your city, and persuade them that you can bring something to their band.

I guess it feels for me in the band’s career that there’s just been so much luck involved. All you can really do is do your own thing, and try and do something that you think is good. And you kind of hope that if you’re doing something that you think is good, then your taste is not so way out that there won’t be other people that like it as well.

For me, I feel like I’ve gotten a fantastically lucky break by meeting Stuart at the time I did, when he had these songs ready to go, and was looking to have a band. I was just kind of lucky that I could play a bit and have the right sort of flexibility to be in his band. I liked enough of the same kind of music as he did to have a rough idea what he was trying to do, and I was able to make a contribution to that.

JM: Do you want to set the record straight about anything about the band? Are there any rumors or misconceptions floating around that bother you?

CG: No, I don’t mind. If there are things floating about that aren’t true, I kind of don’t mind, you know, conflicting stories. Because there is a lot of stuff out there that we initially just said as kind of a joke in the early days, or it’s been written as a joke by our old manager on a website and then it goes on Wikipedia as factual information. I sort of don’t mind that stuff.

JM: Keeps the mystery, right?

CG: Yeah. The truth is probably more boring.

JM: When I was researching for this interview, some places say you were born in Dalry, Scotland, and some say in Stroud, England.

CG: I can give you the truth on that, then. I was born in Stroud, England, and spent most of my childhood in Dalry. I wasn’t born in Scotland. We didn’t move to Scotland until I was in in about my third or fourth year of primary school, seven years old.

JM: One more bit of information that you might find interesting. When I was in college I wanted to study abroad, and my first choice was the University of Glasgow. But as it turned out they had too much interest there, and so they bumped me to Swansea instead. I always that that it would’ve been fun to have gone to Glasgow.

CG: Yeah, Glasgow is a cool town to be a student in, definitely. How was Swansea then? Did you enjoy your time there?

JM: Oh, I had a great time. I did travel around, and spent one day in Glasgow to get a sense of what it was like. It had a gritty feel, but you got the sense of a real good vibe. This was the early ’90’s.

CG: Yeah, it was a pretty happening city. It still is. The kind of vibe that was going on in Glasgow in the early- to mid-90’s was what brought the band together. Sarah [Martin, violin and vocals] moved out quite deliberately for the music scene. You know, growing up in a small town twenty or thirty miles away from Glasgow, just the fact that there were bands like Teenage Fanclub and The Pastels who were making music that you really liked, and were staying in Glasgow rather than moving down to London, or wherever. It was quite inspiring as a kid to know that there was a good music scene where you were growing up. It made the idea of aspiring to be in a band and make records seem realistic rather than an unrealistic pipe dream, because there were people doing it who seemed like real, normal people, not aliens or something, you know?

JM: The Beta Band were from Edinburgh, not Glasgow, right?

CG: They were from the East Coast, up in Fife a bit north of Edinburgh. I know John Maclean from The Beta Band a bit because he was cousins with our first manager Neil [Robertson], and then I crossed paths with him doing DJ stuff from time to time as well. They were a really incredible band.

Discussion

No comments for “Interview: Chris Geddes”