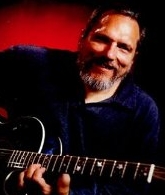

Jorma Kaukonen was the lead guitarist for the Sixties psychedelic band Jefferson Airplane, which is best known for the hits “Somebody To Love” and “White Rabbit” from the album Surrealistic Pillow. His signature song is the instrumental “Embryonic Journey” from the same album. Other acclaimed Jefferson Airplane albums include After Bathing At Baxter’s, Crown of Creation, and Volunteers. As the Sixties wound down, Kaukonen and Airplane bassist Jack Casady’s attention shifted to their new band Hot Tuna, which focused on acoustic and electric folk- and blues-based music. Kaukonen has also released multiple solo albums, including 1974’s masterpiece Quah. Kaukonen continues to tour in Hot Tuna, and with his wife owns and operates the Fur Peace Ranch which runs a yearly music and guitar camp.

This interview was conducted by phone on February 23, 2011.

Jeff Moehlis: What can we look forward to at the upcoming Hot Tuna concert in Santa Barbara?

Jorma Kaukonen: This is not a typical Hot Tuna show. Normally we just tour by ourself, as I think most people who are interested in us know. This thing is actually more of a showpiece. We have the great Charlie Musselwhite, a great bluesman, Jim Lauderdale, a great singer-songwriter, a great player. And G. E. Smith is on the tour also.

We start off on the show playing five or six of our acoustic numbers, and we sort of add people as that part of the show goes on. Jim Lauderdale comes on and plays some songs; we back him up, we sing with him. Charlie comes out and does some stuff.

Then after the break we sort of do the same thing, but electrically. It’s really a lot of fun. It’s kind of hard to describe, it may sound silly, but it’s really a great show. We’ve been having a lot of fun with it, and it’s been very well received.

JM: Will you be playing songs off the new Hot Tuna album Steady As She Goes?

JK: Sure, absolutely.

Hot Tuna has been through a lot of different personnel. It’s always [bassist] Jack [Casady] and myself, obviously. The last Hot Tuna studio recording was made 21 years ago now. We recorded [the new one] in November of last year. We’ve been working with Barry Mitterhoff who’s a member of Hot Tuna also, a guy that I work with all the time, a great string player. He plays mandolin-like instruments, tenor guitar, etc, etc. Plus a fine drummer named Skoota Warner.

My last solo record was produced by Larry Campbell at Levon [Helm]’s place, so when Jack and I got an opportunity to do this, we also did it at Levon’s place. Larry produced it, and he and his wife played and sang on it also.

An obvious question is, why did you wait so long to do another album? The plain and simple answer really is, and I don’t think we thought about it like this, because I don’t sort of plan my life out, but the time wasn’t right. But I wrote a bunch of new songs for this, Jack and I co-wrote some songs, we wrote with Larry. The moment was just right for a team effort to make a good album.

JM: Is the new album a mix of electric and acoustic, or more one?

JK: You know, because of the stuff that Hot Tuna does, electric and acoustic, and like the show we were just talking about, that’s a valid question. But it’s not really like that. I mean, the answer to your question really is, yes, it is a mix. But I don’t really think about it like that. It’s just songs. Some of the songs tend to be more acoustically oriented, and some of them are more electrically oriented.

JM: I see from the track list posted online that album covers Reverend Gary Davis, and I know he’s a longtime influence of yours. Did you ever interact with him while he was still alive?

JK: Not in the same way that guys like Stefan Grossman and Ian Buchanan, the guy who taught me, etc, did. My connection to Reverend Davis was this gentleman Ian Buchanan, who’s long since passed away. I moved to New York for a while, and I didn’t have – I forget what Reverend Davis was charging, six bucks and hour or whatever – I didn’t have that kind of money then. I was working at a hospital for 75 bucks a week before taxes. You know I was hanging out in the Village all the time, and because my friend Ian knew the Reverend I got to see him many times. But even though I didn’t study with him, I did get a chance to see him live.

And when I moved to California later on – because I got a chance to meet him also, and he would come to California and play – one of the things that always made me feel good was that I would say “Reverend Davis, it’s Jorma Kaukonen”, and he would remember me. Now years later I thought he was just being polite, my friend Ernie Hawkins, one of the Reverend’s students who lives in Pittsburgh, told me, “No, if he said that, he remembered you.” And that always made me feel really good.

JM: My first exposure to Reverend Gary Davis was on your first solo album Quah. You know, sometimes you read people say, “that’s my Sunday morning album.” And for me, that would be my Sunday morning album.

JK: That’s a high compliment. I have to say even after all these years, I’m still extremely pleased with that album myself.

JM: Can you describe a little bit about how it came together the way it did?

JK: Well, you know, Hot Tuna was already in existence at that time, in its sort of nascent stage. But I had this buddy Tom Hobson, that was on Quah. If Tom were alive today, he would just be an alternative singer-songwriter. But back in those days, because that category didn’t really exist, he was an extremely quirky, kind of country oriented folkie, and I just loved his stuff. You know, when I moved to California in 1962, I met Tom. He was a little bit older than me, and he was married at the time, which meant there was always food at his place. He had kids, and stuff. And so we hung out a lot, and he sort of introduced me to folk scene, and I learned a lot of stuff from him.

So when the Airplane got our Grunt label going, I just really wanted to do something with him. Now we really didn’t play the same style, so we didn’t play much together, which is the reason I wanted to split the album with him on one side and me on the other. And he was just too bizarre for RCA at the time, so I wound up with more songs. But anyway, it was sort of my homage to a guy that really, in a way, was kind of like a musical father to me in the very early Sixties. And so we got a chance to do it, and Jack produced the album for me, and it was just really a lot of fun to make it. I’d written a couple of songs, I guess “Genesis” is one that comes to mind mostly, and I’d recently learned Gary Davis’ “Light of this World”. I mean, stuff that’s just become staples in my musical life all came together on that album.

JM: Before Quah and before Hot Tuna, and even before Jefferson Airplane, I was reading that you backed up Janis Joplin on guitar. How did that come about?

JK: Well, it sounds sort of like you got a gig in Janis’ band, you know, the way you talk about it like that. But the way it came about, simply, was that when I moved to California in 1962, one of the first weekends I was there I went to a hootenanny – we had hootenannies back then in San Jose, which is where I was living – and a bunch of guys and gals would come down from Berkeley and from San Francisco, and Janis was one of them. And she was a great singer, and even though she played a little guitar, we got to talking, and she realized that I knew a lot of her Memphis Minnie stuff, and her style. So she asked me to play with her, and it was a lot of fun. And so, on a number of occasions after that, when she needed somebody the Penninsula I would get the call.

JM: What sorts of venues did you play, was it like coffee shops?

JK: Yeah, exactly, you bet. You’re always fighting against the roar of the espresso machine.

JM: Well, there’s a tape also, as you probably already know, called the Typewriter Tape. So it was also fighting with typewriters?

JK: Right, yeah. We were rehearsing for a gig we were going to do at the Coffee Gallery in San Francisco, I’m guessing that was made in ’64. I was married to my ex-wife, that was her. She was from Sweden, and she was writing a letter home.

Sometimes people think that the typewriter’s part of the music, or “I can’t believe that she was playing while you were recording”. We weren’t really recording. I had a tape recorder, I turned it on all the time. Janis and I were just practicing songs together.

JM: Fast-forwarding a little bit, how did you get involved with Jefferson Airplane?

JK: I was going to school at the University in Santa Clara, and Paul Kantner had dropped out the year before I got there. We’d met through a mutual friend, and he was a folkie, too. So we sort of moved in the same circles. In 1965 he’d moved to San Francisco, and he met Marty [Balin], and they were putting this band together. It wasn’t called the Airplane yet, and he asked me if I’d be involved, and I sort of agonized over this because… I didn’t know what rock ‘n’ roll was anymore, you know, but I went up and I tried out. It was seductive, and it was fun. And there you go.

JM: Looking back, do you have a favorite Jefferson Airplane album?

JK: You know, that’s a good question. I don’t think we did anything that I didn’t like. But I really think, honestly, my favorite one is Surrealistic Pillow.

JM: For me, I guess that was the first one that got me into Jefferson Airplane. But I like that the music and the albums really evolved. They didn’t sound like that one.

JK: You’re absolutely right. They absolutely evolved, no question about it. And really, in terms of what the Airplane wound up sounding like, the birthplace of that was Surrealistic Pillow.

JM: Were the instrumental arrangements for a typical Jefferson Airplane song carefully planned out, or was it spontaneous in the studio?

JK: The Airplane songs, as you know, especially after Surrealistic Pillow, tended to be very complicated. In those days we rehearsed endlessly, endlessly. We went through the kind of stuff that nobody… I mean, some of us were married at the time, and there was a while where we all lived in a two-level apartment in West L.A. I mean, that’s the kind of stuff that no sane adult would do, you know? But the upshot of that was that we rehearsed endlessly, and most of the songs required a lot of preparation because of the many parts of them. That said, the parts themselves weren’t scripted.

JM: I think of a song like “Wild Tyme”, which is pretty short, but you have the very cool psychedelic guitar part over it, and the chord progression isn’t trivial. Obviously it took some work to do that.

JK: You know the deal. To get a chance to record in a studio back in those days was a huge deal. It took a lot of money, and unless you had a record deal it wouldn’t happen. Today, I’ve got a thirteen year old son that can record stuff like that in Garage Band on his computer. And that’s great, because it frees all these artists, of all ages, it frees all of us from the necessity to have somebody with money backing you, and perhaps requiring something in return. I mean, anybody can do that now. But in any case, in those days it required money.

For example, Surrealistic Pillow was a 4-track recording, our first record Takes Off was a 3-track recording, no noise reduction. You could only do maybe two overdubs without loss of sound quality – the tape degraded. So most everything was done live, which required rehearsal, and you really had to nail those parts in an overdub, otherwise you wrecked the track on the tape. Now, you can take three years to finish [laughs]. I’m thinking maybe about a Hot Tuna Auto-Tune album – no, just kidding.

JM: A club mix.

JK: Exactly.

JM: With so many talented musicians in Jefferson Airplane, did you find it difficult to get your ideas heard?

JK: No, as much as we haggled about trivial things, we never haggled about music. You know, I didn’t write much. I learned to write songs in the Jefferson Airplane. I didn’t write much, but every time I wrote a song my pals in the band heard it, and they helped with vocal harmonies and all that stuff. So the answer is that everybody was very supportive about each other’s art.

JM: You were at a lot of key events of The Sixties. I was wondering if you could reminisce a little, starting with the Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park?

JK: Right, well, you know, it’s funny when you look back, because there were so many things that in retrospect seem to be sort of iconic events – the Human Be-In, Monterey Pop Festival, Woodstock, Altamont. I mean, all those things. It’s just what was going on in our life, and I don’t think anybody ever thought about them as being seminal events one way or the other. Things like the Human Be-In – I was born in 1940, nothing that even vaguely approached that would have existed in the world that I grew up in. And all of a sudden, all of these extremely odd things were happening in the Sixties, and it was like the Wizard of Oz, where it turns from black and white into color.

JM: You mentioned Woodstock. What was your Woodstock experience like?

JK: Oh boy. You know, we had been to the site two weeks before the concert, so we saw them sort of getting it together. We just went in for our day. I think the thing that really is very difficult to describe adequately is when you stood on the stage – and I do remember this – you stood on the stage and looked out and saw that sea of people. Nothing can adequately describe that. And that feeling that the world that was sort of evolving in that moment became “real”, if you know what I mean?

JM: Not long after Woodstock there was Altamont, which you also mentioned. What do you think went wrong there?

JK: Well, you know, I guess it’s easy to be a Monday morning quarterback after something like that. I mean, first of all, I’m sure you’ve probably driven up on 580, where Altamont was and is. It’s a wind generator farm now, and that’s what it always should have been. I mean, there were no sanitary conditions, it was just a really poorly thought out place to have any concert, much less a free concert with a lot of big stars and a lot of people going to come. It was poorly planned. I mean, you can assign blame to a lot of people, but when you look at that area today, when you drive over that road from San Francisco, it’s like, “What were we thinking?”

JM: I had the pleasure of interviewing Paul Kantner about a year ago, and I was asking him about Altamont. He was talking about how Marty got hit onstage.

JK: He did!

JM: What was the band’s reaction?

JK: If you see the movie, you will notice that Jack and [drummer] Spencer [Dryden] and I played on until finally, I think, one of us got pushed over the drumset, which pretty much ended that portion of the show. I guess Marty had got in some Hells Angel’s face, and he got hit, yeah. I mean, once again, you know, all those things were just accidents waiting to happen. It’s easy to look back on it. At the time, “Yeah, we’ll do a free concert, that’ll be great!” Poorly thought out, I say from many years later.

JM: What were the origins of Hot Tuna?

JK: Well, Jack and I have been playing together since 1958, and we’ve been buddies – he’s my oldest buddy – and we always had something going on. It wasn’t always Hot Tuna, but we always had something going on. He and I started working out what became the first Hot Tuna album, the acoustic album, in hotel rooms when we were on the road with the Airplane. And it sort of gained a life of its own.

Then we messed around with various different electric incarnations. Marty was in one of the early versions of Hot Tuna. Joey Covington. This friend of mine Paul Zeigler who was staying with my brother. A lot of different people in the rock ‘n’ roll version of it, just because the rock ‘n’ roll was a little bit different from the Airplane rock ‘n’ roll, even though we used some of the same people. It just started out as something that was fun to do because we could, and it sort of gained a life of its own and it became something. It ultimately became something that was more compelling for me and Jack than the Airplane was.

JM: You mentioned that you’ve played with Jack since 1958. What does Jack bring to the music?

JK: Oh gosh. We played a show last night in Durham, North Carolina, and we were doing one of these old Hot Tuna songs, “Funky #7”, and there’s this bass solo. I was standing with my buddy Barry at the side of the stage watching, and I go, “Where is he going to take this tonight?”

Jack is an amazing musician. His voice is the bass. But through that voice he tells a lot of stories. When you’re playing a song he’s got powerful parts that make the rhythm section drive the song. But in all that, and especially when he gets a chance to solo, he never does the same thing twice. Now, listen, I’ve been playing the guitar for a long time, and I’m pretty good at what I do, but I have a realm, I have a roadmap of things that I draw from to do stuff. Every now and then something magical happens, and you try to remember it. But, you know, you play what you learned. Now, I don’t know what goes on inside Jack’s head, because we’ve never had this conversation, but I’ll tell you, he never ceases to amaze me with the things that he comes up with. It’s like a bottomless well. That, and the fact that when we play together he always listens to what me and the other guys do. He listens, he interacts. If marriages were like that, there’d never be a divorce rate.

JM: Can I ask for your reflections on a few specific songs that you’re known for? First, the one that people probably will still be listening to a hundred years from now, “Embryonic Journey”.

JK: Wow. Well, you know, “Embryonic Journey”, I wrote that in ’62 or ’63. At that time, I’d only been fingerpicking for two or three years. It’s one of those things…

You know, people used to ask Reverend Gary Davis where he got a song, or how he wrote a song, and he’d go, “I didn’t write that song. The Lord give it to me.” Then he’d tell a story about it. It was an inspiration, it was something that just happened. I happened to have a friend who had a tape recorder running. I was just messing around when I did what became “Embryonic Journey”. Later on I listened to all that – “I think that could be a song.” I never thought of myself as a songwriter. I never thought I’d even ever write a song back then. It truly popped up, and I was lucky enough to be able to catch it.

JM: I remember being surprised on the last episode of the TV show Friends that suddenly they played that song. I hope you got a lot of payback for that.

JK: Well, there’s not much money in that, but obviously I was thrilled when that happened. Now with that Friends episode, this is funny because I had never really watched Friends, it’s just not my kind of a show. But I knew it was popular, and at the time a lot of my friends’ kids really loved it. Well, anyway, they had a number of songs in the queue for using for the closer, and none of us knew which song was going to be picked. If you remember, the last episode of friends was a two hour special, and the first hour was a retrospective of all the others. So here’s me, who’s never watched Friends. I turn it on, I sit through the second hour, the closing. It gets up to the top of the hour, and I thought, “I guess they’re not going to use it”. But if you recall, the show actually ran like eight or nine minutes after the hour. And there it was at the end. I flipped! I go, “Wow, they used the song!” And then later I got emails from these friends of mine, who at the time had mostly teenage daughters who loved it. “We used to think your music really sucked, dad, but now we really like it.”

JM: Another song from Surrealistic Pillow, “She Has Funny Cars”, which I understand was co-written with Marty?

JK: With Marty and a friend of ours named Steve Mann, who has passed away since also. Yeah, I remember it was early in the Jefferson Airplane stages. We were in this apartment that I had on Divisadero, it’s long since been torn down – it was near The Fillmore. I remember Marty and Steve and I were sitting around, and we’d just started messing around with these licks. And that lick [sings descending guitar part at beginning of song], Steve and I came up with that, and then we just started putting things together, and we co-wrote the song. It’s a cool song. I wish I still remembered how to play it.

JM: It’s a great opener for the album also.

JK: It is, it is, yeah.

JM: Now on the next album [After Bathing At Baxter’s] you wrote “The Last Wall of the Castle”. What do you remember about that?

JK: It’s been so long since I’ve played or heard that song, that’s a question I probably can’t get you a very incisive answer to. But the question ties in with what we talked about earlier, where the other guys in the band supported those of us that were trying to learn how to write. You know, I have no idea at this point what inspired me to write that, but like I tell my wife when I write things, a lot of times you get maybe a hook, or a musical line, or a lyrical line, and it’s almost like chasing the rabbit down the rabbit hole. You know, you just follow it, and if you’re lucky it comes out someplace interesting. I suspect that’s what happened with that.

Of course, when we started rehearsing, when we got into the studio, because I was playing with so many inventive people, it came together in a much more sophisticated way I’m sure than I could see for it at the beginning.

JM: Another song that is associated with you, although you didn’t write it, is “Good Shepherd” from Volunteers. I think it’s such a cool arrangement.

JK: Thanks. There’s a great story behind it. I learned that song probably in ’62 or ’63 from an itinerant folk singer from somewhere in the San Joaquin Valley named Roger Perkins. And I never knew who wrote the song.

Within the last ten years, however, I found out that the song was written by a guy from somewhere in the Tidewater area of Virginia named Jimmy Struther. He was a blind musician who’d gone to prison for killing his wife. He recorded that one song. And by the way, you can get it. I think it’s on the Smithsonian site for 99 cents. Anyway, he recorded this song, went to prison, and somebody heard it and they were going to discover him when he was released from prison. Never seen or heard from again. But if you download this song, you will hear “Good Shepherd”. Now, he plays it more like a Gospel blues than I did. I play it more like a folk song, you know. But the changes are the same. And they’re such pretty changes, they must have been incredibly inventive for the time that he wrote and recorded the song. I’ve always loved that song. And, for me, I learned in in dropped D. It was my first experience in dropped D – this is guitar geek stuff. Actually “Embryonic Journey” is a dropped D song, too. It’s just a cool sound.

JM: You mentioned before the song “Genesis” from Quah. What are your reflections on that song?

JK: Well, I was going through sort of a turbulent time with my ex-wife, and that’s when I wrote that song. That’s something, we were just having some problems, the kind of problems that Jack and I don’t have [laughs]. A little married man humor there. Anyway, and I wrote the song. That’s one of those things, you know, it’s basically a simple song, it’s a repetitive figure. If I heard that song written by somebody else, I’d go, “That’s a really good song.” I wish I could write them like that all the time.

JM: Also, from Quah – you know I mentioned this was my first exposure to Reverend Gary Davis – you have “I’ll Be All Right” and “I Am The Light Of The World”, which are phenomenal songs and great arrangements.

JK: I love them, too. I remember “Light of the World” has some cool little Gary Davis nuances in it. A friend of mine named Ken Ellis showed me how to do some of the contrapuntal stuff. He opened the door for that, then I made my own arrangement out of it. I’ve always loved both of those songs. I love the melody, the chord structure. And I really love the upbeat worldview of both of them.

JM: Another song – this is now getting to Hot Tuna – “Hesitation Blues”.

JK: That was one of the first songs that I ever learned. “Hesitation Blues”, the version I have, is a Reverend Gary Davis version. I learned it from Ian Buchanan, and I worked out my own arrangement over the years. It’s always been a great song, and again, because when I learned it I wasn’t really interested in sourcing it – I was just interested in playing it – it was many years later I realized that it was a Reverend Gary Davis song, a secular song.

JM: I didn’t realize that.

JK: It’s a cool song. It’s one of the sort of hidden blues things that the Rev did.

JM: As an example of an electric Hot Tuna song, “I See The Light”. Could you reflect on that?

JK: That’s interesting, because a lot of those Hot Tuna electric songs, then and now, I write on acoustic guitar. And so that was written on acoustic guitar, and on the recorded version the basic track has the acoustic guitar in it. Although there’s lots of electric guitar overdubs, too. I don’t know, once again, I think I got an idea from a lyric and I just chased it down and wound up writing the song. But it started out from a fingerpicking acoustic thing.

JM: That’s how you normally write songs? You start out on an acoustic?

JK: Most of the time, yeah. Most of the time.

JM: Do you want to set the record straight about anything from your career in music?

JK: I guess I could say one thing. You know, every now and then people go, “Was the original name of Hot Tuna ‘Hot Shit’?” I go, “No”. It’s from a Blind Boy Fuller song – there’s a lyric of the song that goes “What’s that smell like fish”, and some wise guy who sang the song said “Hot Tuna”. “Wow, that’s a great name for a band.” Anyway, listen, in our defense, it was the Seventies.

JM: I think it’s a great name. And you remember it.

JK: It is, it is funny. Who knows what sort of name is going to stick. But you’re absolutely right. It gives us a lot of ideas for cool T-shirts.

JM: What are your plans, musical or otherwise, for the near future?

JK: My wife and I have the Fur Peace Ranch music school in southeast Ohio. We’re moving into our fifteenth year there. So I teach a lot – that’s a huge part of my life. We have a radio show, we have a 200-seat theater, so that occupies a lot of my time. I have a four-and-a-half year old daughter. When I’m home that occupies a lot of my time, obviously. I’m so lucky because at my age I’m still healthy, I’m still able to do what I want to do. I just want to keep on doing what I’m doing.

JM: What advice would you give to an aspiring musician?

JK: I guess the most important thing is, first and foremost, to love whatever it is that you do. Whatever your muse, whatever kind of music, whatever instrument that you play, you love that first. Every now and then you meet people that are chasing stardom. If that works for you, then that’s great. If you’re lucky it might happen. It probably won’t. But if you love to play music you’ll have a great companion for your whole life.

JM: Last night I went to see to Robin Trower in concert, and afterwards I asked him the same question. There have been a few others that have answered like this. He said, “Become a barber”

JK: [laughs] Yeah, right. I mean, the music business is such a funny thing. Jack and I and my buddies, we’ve been so fortunate because we’ve been doing it, really, all of our life. Not everybody gets that opportunity, but if you want to be a professional musician there’s a lot of stuff you can do. You know, you could play locally, you could teach, you could be a studio musician. There’s just so many sub-categories of all that stuff. But mainly, if you love to do it… I mean, I’ve had the same job all my life, and I’ve been able to do, from a professional point of view, exactly what I wanted to do. It doesn’t get any better than that.

JM: And I’m sure, in many ways, it doesn’t seem like a job.

JK: No, you know what the job is? The job is traveling. I’m on this long tour right now, and I don’t have to drive myself anymore, we have a bus. But I’d rather be home watching my kids grow some of the time. We play for free, we get paid to travel.

I can’t believe Jorma and Jack are coming to SB. I was with Guitar Player Magazine interviewing John Lee Hooker in SF and met Jorma. We played a little dittie called “Deep River Blues” together and really got into it. He is a fantastic musician and totally dedicated to his craft. I have nothing but respect for the man…and Jack…the silent man, is a walking bass. He knows nothing but perfection.